How Former WNBA Star Rushia Brown Is Creating Networks of Care for Retired Players

Sports Illustrated and Empower Onyx are putting the spotlight on the diverse journeys of Black women across sports—from the veteran athletes, to up-and-coming stars, coaches, executives and more—in the series, Elle-evate: 100 Influential Black Women in Sports.

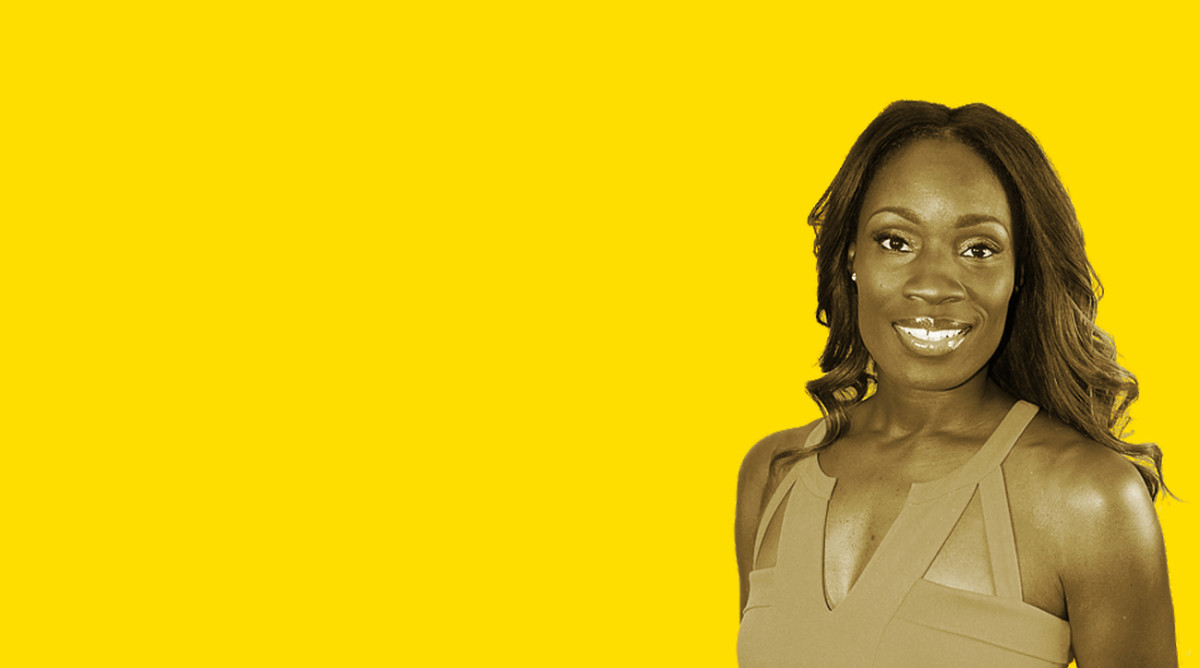

A former WNBA superstar and founder of the Women’s Professional Basketball Alumnae (WPBA), Rushia Brown is accustomed to being surrounded by networks of influential women who uplift one another. What she didn’t anticipate, however, was the lack of support or resources the league provided for former WNBA players upon retirement. After a 10-year career playing overseas in Europe and seven years in the league Stateside with the Cleveland Rockers and Charlotte Sting, Brown founded the WPBA in 2011, the first and only organization structured to assist women who have played professionally in the WNBA or in Europe as they transition back into mainstream society.

In addition to founding and running the WPBA for the past 10 years, Brown was recently appointed as the director of community relations and youth sports for the Los Angeles Sparks, in May 2020. Though it may seem like a natural progression for her, it was an opportunity that recalled some of her earliest memories of her own family, and the unexpected loss of her father as a young girl.

“I was born in the Bronx, but my family and I moved to Charleston, S.C., when I was almost four years old. I would watch sports with my dad, but I was never interested in playing,” says Brown. During her freshman year in high school, Brown’s father was diagnosed with cancer. He passed away a year later. “That’s when I really went out for sports, to keep me out of trouble. I had turned into the problem kid, rebelling because of my dad’s death. I also wanted to find a way to connect with him again, doing something he loved.”

Once she started playing basketball, Brown says she absolutely fell in love with it—"the grind, the results [and] knowing I had control just based on my work ethic”—and the way it made her feel mentally and physically. She says the game helped her learn how to have healthy relationships.

For Brown, the opportunity to work with the Sparks seems fated—Brown’s father was a huge Lakers fan. “Not only that, he was a Pittsburgh Steelers fan,” Brown says of her father. “And I eventually had the opportunity to present an award to [Steelers Hall of Fame running back] Franco Harris. It’s like, everything just came full circle for me.”

That divine intervention seemed to be present throughout the entirety of her career, even when her course appeared to steer off-path. Though she had committed to her dream school, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Brown chose to stay close to her family, still reeling from the loss of her father, and ended up at Furman University, a (very) small Southern Baptist university. “Furman literally was the same size as my high school, and we might've had 4% African American students,” Brown says. “As far as representation, there was little to none, and for those of us on campus, we were primarily athletes. But my time there helped me develop. It showed me what the world was going to look like. I wasn't emotionally ready to do anything else, so it was exactly what I needed.”

During her time at Furman, Brown was also able to further her own networks of care and leadership with other women in the professional sports industry, something that would help her as she transitioned into playing professionally overseas, in Spain, France, Italy, Korea and Greece. “I learned how to build relationships within the game. Not just with my teammates, but other women that played on other teams that I started to build relationships with. Even when I went overseas, I had those same relationships and was able to have conversations and mentorship relationships with other players.”

Three years into her overseas career, in 1997, the WNBA officially launched as one of the first legitimate platforms for women to play basketball professionally in the U.S. “The first year, there were only eight teams. So there were 96 of us,” Brown says. “I was afraid to take time off, for fear of losing my opportunity. I made sure that I played for as long as I could. There were very few African American women or men in that space in leadership positions. It's ironic because if you look at the court, it's 85%—but it's like all sports. The athletes on the field may be represented by us, but the front offices are not.”

After some injuries, Brown listened to her own body and retired at age 30. And that’s when she began to question: What does life look like for professional players in the WNBA, once they retire? What kind of support systems were available for these women? Seeing a desperate need for the same type of aftercare players in the NBA seemed to be receiving upon retirement, she officially founded the WPBA in 2001.

“I ended up starting that out of a necessity,” she says. “One of the young ladies I knew was a two-time WNBA All-Star. She'd played in the league for 7–8 years and had a great career. People knew she had mental health issues, but nothing was ever done to help her. Eventually we found out she was homeless. I was blown away.

“I formed the WPBA to help to serve other women, to serve my sisterhood. When you go from being a star athlete to a regular Jane, it's tough. You’ve got to figure out who you are, and what you are, without that game. We focus on financial assistance, higher education, job placement, workshops, events. There’s just something to be said about the sisterhood. We realized, we are our greatest resource,” Brown says.

Now more than 20 years into her career in athletics, Brown is ecstatic about the strides she’s made, and about the work that still remains in shaping the next generation of empowered athletes. But her most important work remains off the court.

“My greatest joy in life is my 9-year-old. I am a consummate believer: In order to raise strong, empathetic, compassionate, hardworking, driven women, we have to be them,” she says. “Every time I do something, she is my first thought. What impact is this going to have on her? But she sees her mommy working hard. She understands, I'm not just out here kicking it. This work is about impacting lives.”

Naya Samuel is a contributor for Empower Onyx, a diverse multichannel platform celebrating the stories and transformative power of sports for Black women and girls.