Lisa Purves was 18 the first time she reached out to the professional wrestler who’d fathered her. On that occasion, he hung up. A few years later, she tried again and left a message. She never heard back. Before she turned 30, she once more got her dad on the phone and told him who she was—and once more he hung up. Lisa says she went so far as to ask other wrestlers over the years to speak to her father for her, but nothing ever came of it.

Growing up, Lisa only ever told her best friends about her dad, who spent more than two decades in the ring, climbing to the upper ranks of WWE. “I was really embarrassed that my father didn’t want me,” she says today, at 53. It took decades before she confronted that embarrassment.

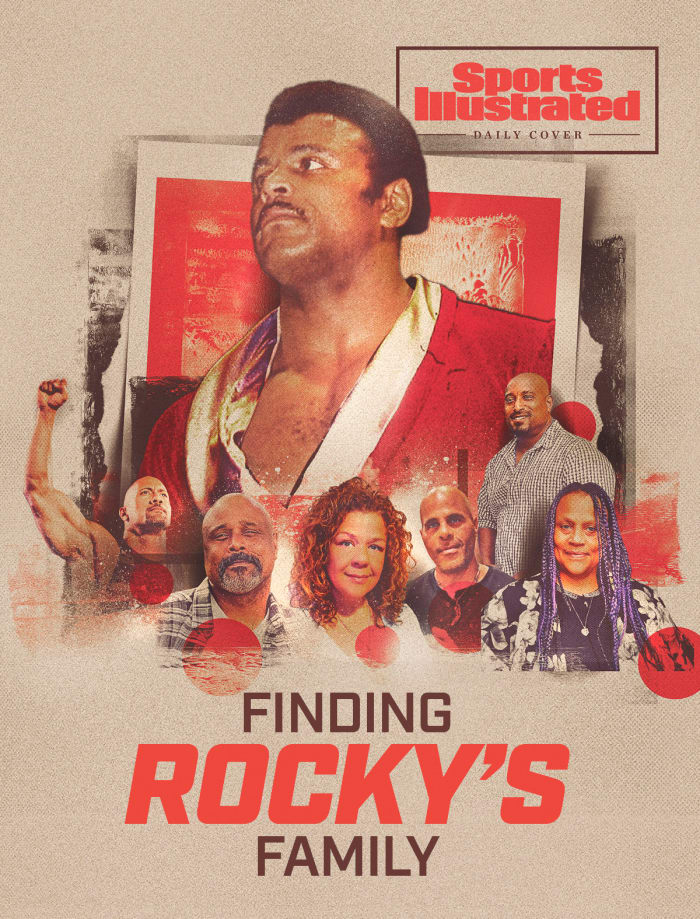

Illustration by The Sporting Press; MediaPunch/Shutterstock (Rocky Johnson); Chris Ryan/Corbis/Getty Images (Dwayne Johnson); from second to left: Courtesy of Aaron Fowler; Courtesy of Lisa Purves; Courtesy of Adrian Bowles; Courtesy of Trevor Edwards; Courtesy of Paula Parsons

Hers was a winding path: A child of her own, right after high school. Nursing courses and hospital work. Then film. She learned screenwriting from a book, and her first script, which she wrote when she was 38, won her a fellowship at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia. She took any job she could get, on movie and TV sets, learning about everything from prop-making to producing. Then, in 2017, a personal project. “I started doing research on what happens when you abandon a child, how it affects their life,” she says. “And I’m like: This is exactly me. Problems with self esteem… . All the s--- that it lists is me.”

Lisa set out to make a documentary about children whose parents knowingly separated from them, but she couldn’t find any subjects willing to talk openly. Then a friend suggested she turn the camera around: “Why don’t you make the documentary about yourself?”

It took some convincing, but Lisa agreed. Only then would she come to see: She was far from alone.

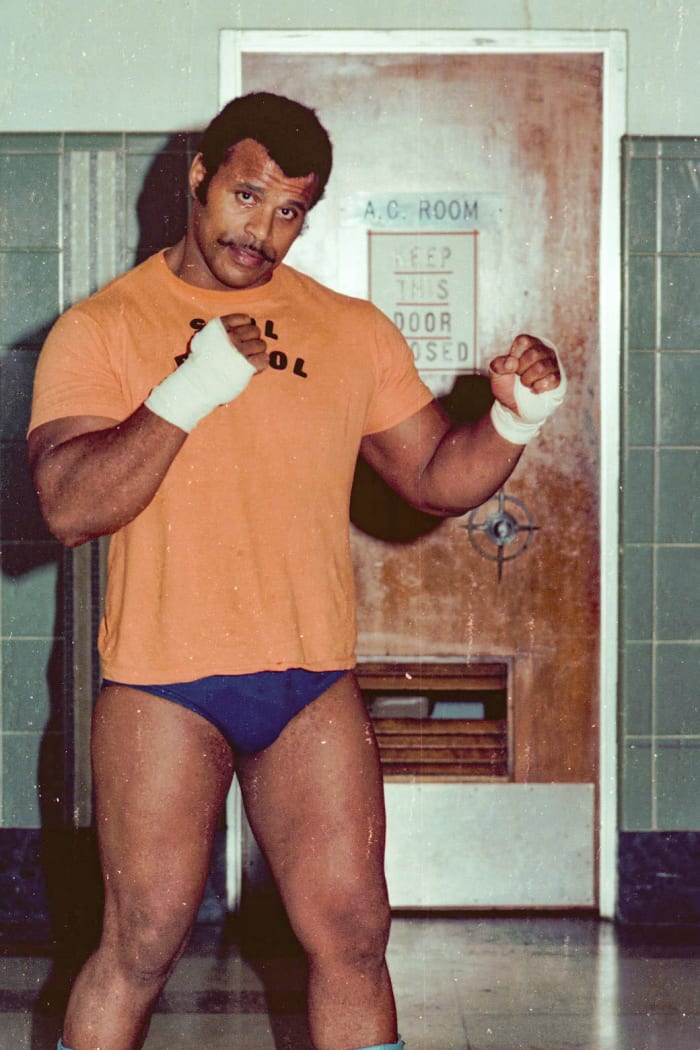

Before Wayde Bowles fathered many children, he was one of many children. The fourth of five boys, he was active early on in boxing and pivoted in his 20s to wrestling. He trained in Ontario and worked his way up in rings across Canada, performing under a name well known today to wrestling fans: Rocky Johnson.

Rocky’s big break came in Los Angeles, and he toured North America for the next 15 years, winning dozens of singles and tag-team titles across territories, culminating in national exposure as he and Tony Atlas became the WWE’s first Black tag-team champions. Years later, wrestling scribe Dave Meltzer captured Johnson’s career in pitching him as a candidate for the Wrestling Observer’s hall of fame, writing that Johnson goes overlooked today, in part, because he traveled so much. In his pitch, Meltzer called Johnson “the best wrestler of the past 40 years when it comes to doing a dropkick series” and deemed him “one of the business’s top athletes of the ’70s, with a career record that is far more impressive than most realize.”

In 1966, before that career peaked, Rocky married for the first time, to Una Sparks, and they had two children, Wanda (born in December ’62) and Curtis (May ’65).

When the demands of the road put a strain on that marriage, Una asked Wayde to stay home, in Toronto, where he had a job lined up delivering fish. He chose instead the nomadic life of a pro wrestler. By the time they officially divorced, in 1978, they had been apart for many years.

Now a major star across the continent, and having officially changed his name, Rocky Johnson married again that year to Ata Maivia, who was the daughter of another wrestler, High Chief Peter Maivia, and a promoter, Lia Maivia. Rocky and Ata by that point already had one child, a son born on May 2, 1972: Dwayne Douglas Johnson, who would one day gain international fame as The Rock.

But young Dwayne wasn’t given the opportunity to be close with his half siblings. Rocky made little effort to connect his children.

Rocky started in one ring, boxing, and pivoted to another, wrestling, where he was one half of WWE’s first Black championship tag team.

Brian Berkowitz/Peter Lederberg Collection

Paula Parsons is 58 today, with four kids of her own. She teaches early childhood education, a job that allows her to provide the kind of stability she lacked growing up in Lucasville, Nova Scotia. Her mother, Thelma, met Rocky in Toronto when Thelma was 19; they carried on a relationship for two years and Thelma ended up having Paula in May 1964, a year and a half after Una Sparks gave birth to Wanda. Later that year, Thelma dropped her child off with her parents, who raised Paula.

Paula eventually learned from her mother who her father was. And she says there’s no question that Rocky knew about his first child. She says he called her twice: once when she was relatively young and again when she was 16. “Promises after promises,” she recalls. “I’m going to come see you. I’m gonna do this; I’m gonna do that. You get your hopes up that he’s going to come. I’m finally going to meet my dad. And nothing comes of it.”

Still, wrestling lent Paula a loose connection to her father. She attended shows at the Halifax Forum, cheering on Leo Burke and The Beast, and in her bedroom she kept a picture of Rocky that she says she talked to at night, asking, “When are you going to come see me?”

“You cry,” she says. “Then you say: What did I do that he doesn’t want anything to do with [me]?”

Rocky Johnson’s fourth child, Trevor Edwards, was born in Montreal on March 23, 1967. He was raised solely by his mother, Doreen, who’d come to Canada from the island of Saint Vincent, in the West Indies, in ’65, and who worked as the live-in help for a doctor in St. Catharines, Ontario. In recalling his teenage years, Trevor says that without a father figure he felt compelled to give off a sense of cockiness—his way, he says, of making clear that he wasn’t some mama’s boy.

Trevor remembers Dwayne Johnson coming onto the wrestling scene around 2000, and how people used to tell him he looked like the rising star. He also remembers that, growing up, his mother (who died in ’15) was never forthright with details about his father. But he did know this: His mom was a huge wrestling fan, and Rocky wrestled in St. Catharines around the time he would have been conceived.

Trevor eventually married and settled in Toronto, just a few minutes’ drive from the home of Rocky’s younger brother by eight years, Jay, who long ago adopted the wrestling name Ricky Johnson. Ricky and Rocky once tag-teamed in Hawai‘i’s NWA Polynesian Pacific promotion to form the Soul Patrol, but the two weren’t particularly close growing up. The boys’ father, James, died when Ricky was four—but still the youngest (and last living) of the five Bowles boys says he was raised with a strong sense of what a parent should be. “My mom told me what a good man [my dad] was and how compassionate he was,” Ricky says. “And I tried to take that with me.”

In June 2017, Trevor, who’s now 55, started sniffing around and through a little Facebook sleuthing deduced where Ricky lived. He buzzed the apartment and left a message, explaining that he believed they were related. Ricky called back that evening, and he invited Trevor to visit. Ricky took note of Trevor’s mannerisms and his walk. And Ricky was convinced.

To be sure, they ran a DNA test the following day, which eventually matched the nephew and uncle. “I hugged him and told him I loved him, and welcomed him to the family,” says Ricky.

Lisa Purves, the filmmaker, was born Oct. 26, 1968, in Vancouver. At the time, her mother, Vera Pinter, lived across the street from a boarding house that hosted wrestlers on the local promotion. The way it was later explained to Lisa: Her mother met Rocky through a mutual acquaintance, and on their first date they went to a Little Richard concert. Soon after, Rocky and Vera moved in together.

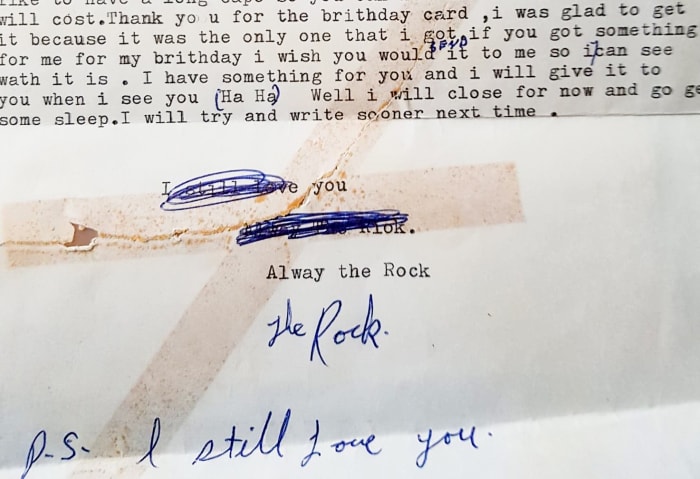

When Vera was four months pregnant, Lisa says, Rocky traveled to a wrestling show. He wrote a letter saying that he’d be back, adding “P.S.: I still love you” at the bottom and signing the note with a nickname he used long before his son ever did, “The Rock.” But he never returned. When he called on the night before Lisa was born it marked the last time Vera would hear from him. She learned shortly afterward that Rocky was already married and had kids.

“She always thought he would come back,” Lisa says. “When I was old enough to understand, she started telling me some bits and pieces.”

Lisa says that after Rocky left Vancouver, his wrestling colleagues did their best to help Vera and her, checking in on the way through town, sometimes delivering diapers or clothes for the baby. Really, though, what she needed was a father, and when she reached out she was turned away.

In one letter to Lisa’s mother, Rocky referred to himself by a name his son would make world-famous decades later.

Courtesy of Lisa Purves

Even in Rocky’s absence, Lisa, as an adult, has found her past to be a constraint. She stayed in Canada, she says, in part to avoid ever crossing paths with her famous half brother, who works in the same industry. “I never wanted to run into Dwayne and have anyone know I was his bastard sister,” she says. But when Johnson came to Vancouver in 2017 to film the movie Skyscraper and everyone seemed to have a celebrity-sighting story, there was a mental toll.

Lisa says she spiraled into depression and could “barely function” for months. She cried every day. She felt unworthy, unlovable and undeserving of success. But talking about those feelings today, she’s careful not to place any blame on the man who has eight times lifted the WWE championship belt, and whose movies have banked upwards of $5 billion worldwide. “Every time I turned around, on the news: Oh, my God, Dwayne Johnson’s in town! I couldn’t get away from it,” Lisa says. “It’s not that I don’t like him. It’s just, when I look at him, I don’t see him. I only see that our dad loved him and not me.”

Of all Rocky Johnson’s children, Adrian Bowles is the most vocal about the torment he felt being raised without a dad. “For a long time I was burdened by the weight of my own sadness, and I became angry,” he says. “That was the fuel. I thought of my father every day of my life. Standing in a mirror, looking into my eyes, having a conversation with myself about why [he left].”

Carolyn Bowles gave birth to Rocky’s sixth child on April 24, 1970, in Truro, Nova Scotia, and she raised Adrian by herself. “She was in love with [Rocky]—she always thought he would come back,” says Adrian, who learned his father’s identity around the time he turned 10. “My mom, she can’t even tell the story; she starts to cry.”

Adrian’s was a tough upbringing, near the poverty line, and it forced him to grow up quickly. “It felt like it was my job,” he says. He remembers chopping wood when he was 11, for the stove. Living off of frozen peaches and powdered milk. Shoveling driveways “until I couldn’t feel my fingers.”

He played football and baseball, and he studied boxing. He met his future wife, Tammy, while he was playing baseball in Hamilton, Ontario, but he gave up any dreams of a pro career when she became pregnant. “I have five kids now,” he says. “I swore to be the best dad. I was worried I was going to turn out like [Rocky].” (That hasn’t always been easy. For a time, Adrian and his family lived in a van, and his story remains complicated: In 2020, he fled from Canadian police during a traffic stop and was charged with drug possession.)

After Trevor (left) met with Ricky (center), Adrian (right) reached out and the three huddled at a show.

Courtesy of Trevor Edwards

When Adrian was 40, in 2010, he says Rocky called. “The phone rang and I heard, ʻAdrian?’” he remembers. “And I said, ʻYes.’ And he said, ʻYou know who this is?’ I did, instantly—and I’d never heard from the man before.”

“It was a good conversation,” Adrian says of the first and last time he talked to Rocky. “A little gratifying, I suppose—but a little late. It kind of stirred things up inside.”

In May 2014, Adrian, too, found his Uncle Ricky on Facebook. At first they just liked each other’s posts. (Paula developed a similar online relationship with Ricky in early ’19.) Then Trevor posted about his meeting with Ricky, and when Adrian saw that he was emboldened. First he met with Trevor. Then, together, they connected with Ricky at a wrestling show.

Adrian says the contact spurred in him a monumental shift. He remembers how his uncle “grabbed a hold of me in a big bear hug” and then paraded him and Trevor around the show, introducing him to friends. And he remembers the tears of joy that came streaming down.

Aaron Fowler was born June 17, 1970, and he lived in Amherst, Nova Scotia, until he was six. His mother, Jackie, who is Black, married a white man, who Aaron believed to be his biological father. When the family eventually moved to Prince George, British Columbia, with its 1% Black population, Aaron suddenly felt like he and Jackie stuck out. He remembers friends grilling his half brother, who is also white: “Why is your brother Black?”

The way Aaron remembers it, his mom finally told him about his real father when he was 15, give or take—but it was the last she would ever say of it. That was right around the time he and his buddies took an interest in pro wrestling. “I was blown away for a second; I didn’t actually believe it,” Aaron recalls. Being a teenager, though, he put it on the back burner.

Today Aaron works at an agricultural warehouse. He recalls how, when he was 30 or so, he shaved his head for the first time and “everybody started saying, ʻOh, you look like The Rock!’ ” It wasn’t until a decade later, after a family member at a birthday party in Nova Scotia pointed out his resemblance to the WWE star, that he took seriously the idea of further exploring his parentage.

For Aaron, a physical resemblance to his half-brother Dwayne was the start of a path to finding family.

Courtesy of Aaron Fowler

In 2020 he talked to his wife (whose child he had adopted) about the idea of taking a DNA test, and she encouraged him to go for it. Those results, from the genealogy company Ancestry.com, were returned two months after Rocky died of a heart attack, at age 75. Adrian Bowles came up as a half-sibling match, as did Lisa Purves, whom Aaron tracked down online. When Aaron and Lisa first spoke on the phone, Aaron was outside the warehouse where he works, and he cried in his truck. (The siblings have run their DNA against Rocky’s other known brothers, too; each comes up as an uncle match on the paternal side.)

The way Aaron sees it, he has “gained a ton” in confirming who his dad was—meaning the family he’s discovered, even if he has yet to meet them in person. “I can’t even tell you how important or how lucky I feel,” he says.

“I kept [this all] to myself for almost 10 years,” says Trevor. “And when I reached out, it wasn’t to Dwayne. I just wanted to meet my father.”

Each of The Rock’s half siblings makes clear: This is not a story about their wrestler-turned-celeb half brother, who remains actively involved in the lives of his own three children. Johnson has called his relationship with Rocky “incredibly complicated,” even if Rocky was a regular childhood presence. As Dwayne grew up, Rocky moved the family wherever the wrestling life called for. In a 2021 interview with Vanity Fair, Dwayne detailed how Rocky treated Ata, including an incident in the late ’80s, when Dwayne was 15, in which Rocky abandoned his wife on the side of a highway. Later, Dwayne fought heatedly with his dad about Rocky’s autobiography, which, Vanity Fair wrote, “aggrandized his father at the expense of the truth.”

Rocky Johnson’s other kids know, though, that when they talk about Rocky, it’s inevitable that people will think they have their sights set on the eighth—and most famous—of his known children. If they think much about Johnson at all, they say it’s largely as the child their father did embrace. “All I ever saw on TV was Rocky talking about Dwayne and how proud he was,” says Lisa. “And it was really painful.”

That dynamic was put under a spotlight in 2008 when Dwayne introduced his father at Rocky’s WWE Hall of Fame induction ceremony, and again on the NBC sitcom Young Rock, which for the last two seasons has detailed various aspects of Dwayne’s childhood, including his complicated relationship with his dad (played by Joseph Lee Anderson). Rocky is portrayed at times as a loving husband and father, and other times as a con artist and thief. Trevor has watched both seasons. “They touch on the positive and negative side of growing up with Rocky as a father,” he says. “I respect that they didn’t try to sugarcoat it.”

The siblings know Dwayne has nothing to do with their hurt. “Dwayne doesn’t owe us anything,” says Lisa.

Ron Elkman/Sports Imagery/Getty Images

That’s a Rocky thing, though; not a Rock thing. The siblings acknowledge that. Adrian: “Dwayne has nothing to do with the decisions that his dad made; he doesn't even know who we are.” And Lisa: “Dwayne doesn’t owe us anything.”

“We just want to be recognized,” says Paula. “We sat on the back burner forever. [Rocky] was our dad just as well as Dwayne’s.”

In the end, it took not one but two documentaries to bring Rocky Johnson’s family together. In 2018, after Lisa Purves had started working on her movie (but before she put the lens on herself), she saw a Facebook post by a filmmaker she knew through the Vancouver art scene. Fulvio Cecere had directed a documentary, 350 Days, about the highs and lows of life on the road in the pro wrestling circuit, and he’d posted a photo of himself with Rocky’s brother Ricky. Lisa says she saw a sort of happiness in the man she knew to be her uncle, so she took a chance and messaged him.

“He reached out right away, and we talked and I cried, and he cried,” says Lisa. “And then he told me about Paula, Trevor and Adrian. So I reached out to all three of them. This all happened in one day. I was so excited—what a day!”

A month later, Lisa arranged for her newly discovered family to share a six-bedroom Airbnb over a weekend in Toronto, and she brought a camera crew along to document the moment. Trevor lived nearby; Adrian came down from North Bay; Paula flew in from Halifax and Lisa from Vancouver. (Aaron was not yet in the picture.) They each brought their spouses and kids along, 17 people in total, plus one big dog. Trevor barbecued one night, and Paula cooked a huge family breakfast. They drank and shared stories and built a bonfire. The kids kicked around a soccer ball and they all went to a football game—one of Adrian’s sons happened to be playing in Toronto that weekend. And when the siblings struggled to express themselves, their kids stepped in, sharing their own feelings of emptiness, having never known their grandfather.

Ricky was there, too, with his wife, Jeanie, and they all grilled him about his brother. “They deserve to be loved, like any other child does,” says Ricky, who’s now 68. “Whether they’re rich and famous or not.”

Ricky says that Rocky was aware of at least some of the children he fathered across Canada, outside of Wanda and Curtis and Dwayne, and the fact that he didn’t keep up with them was a point of conflict in the brothers’ relationship. (Their tag team is not mentioned at all in Rocky’s autobiography, Soulman—a book that at one point I spoke to Rocky about writing with him.) “We talked many times, just me and him, one on one,” Ricky says. “We fought about [the way he treated his family], argued about it. That’s the way he chose to live his life.”

The Toronto reunion (minus Aaron), from left: Paula, Ricky, Jeanie, Adrian, Lisa and Trevor.

Courtesy of Lisa Purves

Ricky took the other path. “I keep reinforcing that I love them,” he says. “I tell them that all the time, all the kids.” Now Uncle Ricky and Aunt Jeanie talk, text and hold regular Zoom meetings with their nieces and nephews. There was a mini reunion for Ricky’s 65th birthday. Lisa has flown out to stay with Paula. Adrian crashed on Lisa’s couch for a bit. And they all mourned with Lisa when her 33-year-old daughter, Natasha, died unexpectedly last November. “We’re all close because of [Ricky],” says Adrian.

Looking back on the day they all came together, Paula calls it “the greatest moment of my life.” Lisa, remembering the tears and laughter, says it was “a healing weekend.” Adrian describes how Lisa yelled out “My baby brother!” when they met, and how they had an instant bond, “like I’ve known her forever.”

As part of that get-together, Lisa arranged for more DNA tests, and the results again confirmed, as much as a DNA test can: They’re all family. All Rocky’s children. Lisa, though, believes their father had even more kids. “I’m still searching,” she says.

Her film, which is still in production, is tentatively titled Just Call Me Lisa. She says she has already faced personal attacks over the project, but she wants people to know: “I’m [talking about this] now because I have been silent my whole life about what hurts me the most. It’s time to finally have my voice heard, so I can be free of my painful past.” (She says that Wanda and Curtis declined to participate in the doc, and her request to Dwayne’s team went unanswered.)

Lisa hopes that by sharing her story, and her siblings’ stories, others can heal too. “There are millions of other kids just like me,” she says, “and I want to [tell] people: Face your shame. If one person heals from watching this documentary, then putting my pain in public is worth it.”

More SI Daily Cover Stories:

• Kelly Slater Won the Super Bowl of Surfing at 50. So, What’s Next?

• NBA Draft? Nah. He’s Following the Money, Right Back to School.

• Is Chet Holmgren the Future of Basketball?