The Pigskin Holy Trinity

In this story:

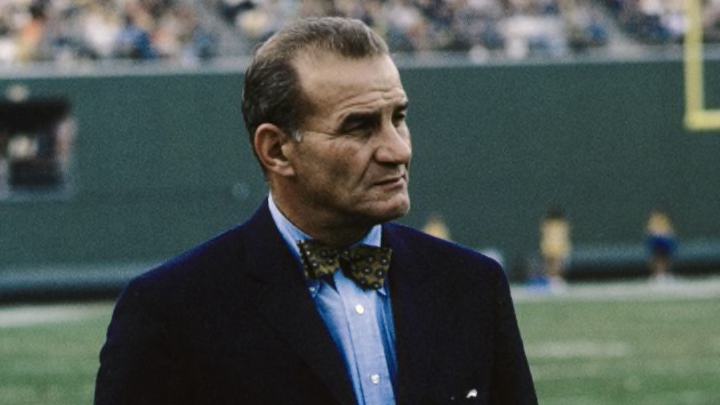

“The big play comes from the pass. God bless these runners because they get you the first down, give you ball control and keep your defense off the field. BUT, if you want to ring the cash register, you have to pass.” (Sid Gillman, circa 1960)

From my younger days in my early 20s as an aspiring college offensive assistant coach, when I first met Sid, even to my days as an offensive coordinator and play caller with the Oakland (Los Angeles) Raiders, those words from the dynamic and generational offensive guru Sid Gillman always rang with a deep resonance.

When in doubt, GO DEEP! Make that cash register ring!!

I remember, often fondly in my now elder days, the words of the great Raider cornerback Lester Hayes, as he used to chant “3 and out” before the Raiders defense took the field.

My complementary response was, “one and done, and get the PAT team ready,” because that was the ultimate in an offensive drive for the deep ball mantra of the Raider silver and black.

No disrespect, but forget the words of the late, great Kansas City Chief head coach Hank Stram and his 65 Toss Power Trap because Uncle Sid was all about going deep and making that cash register ring.

No disrespect to Hank’s “matriculating the length of the field,” but we were going over the top!

One and done, baby! When in doubt, go deep!

However, that was not always the identity of the National Football League.

Back in the days of my youth in the early and mid-1950s, before the NFL made it to the national TV market when we had only three channels with rabbit ears and tin foil on the antenna for better reception, it was a 3 yards and a cloud of dust offensive style with closed formations and a flanker receiver labeled as a “W” because he really was a wingback on the flank of the tight end. 10 passes per game was an offensive explosion!

Today’s fans are enamored with the pass happy NFL where QBs throw for more yardage and TDs in a single game than about which the QBs of the 50’s and early ‘60s only could dream.

But, remember, we just did not get there over night!

How did today’s NFL evolve to where it generates over $10 billion in gross revenues; attracts a global viewer audience of tens of millions of fans; dominates the airwaves and is the main theme of the 24-7 sports talk radio?

Definitely not by accident, and surely not by the intent and design of three of the greatest minds ever to grace the game with their intellect as they were preoccupied by the Xs and Os and the resulting TDs rather than enamoring a viewer audience.

Sid Gillman, Don Coryell and Bill Walsh, without a doubt, have to be acknowledged as the three greatest minds whose creativity during the 1950s, the 1960s and even into the 1970s and 1980s elevated the maturation and accelerated the sophistication of the game to where today’s young guns and so-called offensive gurus are relishing in the headlines and accolades as they rack up the yards and TD passes like it is a backyard pick-up neighborhood game.

Somebody had to do the dirty work and to lay the foundation, and it was these three masterminds who paved the way for today’s game that makes that cash register ring!

Sid achieved notoriety with his vertical and screen concepts; Don excelled with his mastery of crease and seam concepts and read screens while Bill achieved greatness with his design of the triangle reads and horizontal concepts tied to precise QB footwork.

The innovator and arguably acknowledged “father of the modern-day passing game,” which eventually was labeled “the West Coast Offense,” actually can be traced back to the post World War II era where it had roots in the Midwest. That 32 year-old named head coach at Miami of Ohio University, the “Cradle of Coaches,” was none other than Sid Gillman.

Besides putting points on the board while compiling an 81-19-2 record during a 10-year span, Gillman and his staff also produced great collegiate and professional coaches such as Johnny Pont, Bo Schembechler, Bill Arnsparger, Paul Dietzel, Ara Parseghian, Carmen Cozza and Jack Faulkner among others there and in the following years with the Cincinnati Bearcats before landing in 1955 as the head coach of the Los Angeles Rams, co-owned by Dan Reeves and Edwin Pauley.

Sid was in his hay days beginning with his inaugural season in 1955 as QB Norm Van Brocklin, wide receivers Elroy “Crazy Legs” Hirsch and Tom Fears and running back Tank Younger lead the club to the Western Division title.

The loss to the Cleveland Browns in the championship game, which happened to be the last title game appearance for the Rams franchise until Super Bowl XIV in January 1980, definitely stung but did not deter from Gillman’s continuously evolving concepts in the passing game.

The launch of the newly formed American Football League (AFL) with its eight franchises in 1960 actually provided a national audience with exposure to Sid’s vertical game, mastery of field balance and distribution of receivers and the concept of “flare control.”

Gillman had left the Rams to accept the head coaching position of the Los Angeles Chargers, and in formative discussions, owners and coaches in the new league quickly reached a consensus that for their league to survive and to attract a national following it had to be different than the NFL, and that meant the ball had to be in the air.

The AFL even introduced a game ball more streamlined and aerodynamically engineered for its pass happy league.

Sid’s theory of the hypotenuse of the “nine route,” split rules and types of releases and route stems that varied predicated on specific patterns called, the concept of “offset throwing” and the emphasis of different trajectories for specific routes became dominant fixtures in his offense as the Chargers, who relocated to Balboa Park in San Diego after the AFL’s inaugural season, swept to divisional titles in five of the league’s first six seasons.

Gillman was the first coach to produce divisional champions in both the National and American Football Leagues, and his Chargers 51-10 dismantling of the Boston Patriots in the 1963 AFL title game featured the offensive weapons of WR Lance Alworth, running backs Keith Lincoln, Paul Lowe and QBs Tobin Rote and John Hadl, protected by future Hall of Fame offensive tackle Ron Mix, all of whom employed to perfection Sid’s concepts.

While the Chargers with Gillman at the helm were racking up the points and posting prodigious pass yardage numbers, there was a college coach just down the road to the east located on Montezuma Mesa who happened to be carving his own niche in college football annals.

This coach often would bring his team and assistant coaches to Charger practices to watch how Gillman ran his practice, installed and taught his pass game and protection schemes and how Sid and his staff drilled and refined position player techniques necessary to execute to perfection Gillman’s game plans.

This coach was none other than Don Coryell, who seasons later went on to achieve national acclaim for an offense that became known as “Air Coryell.”

The journey for Coryell’s eventual air assault ironically took shape on the ground with the run-oriented “I” formation that he featured as head coach at Whittier College from 1957-1959, where he won 3 consecutive SCIAC titles, and in the 1960 season where he served as an assistant to John McKay at USC.

There was virtually no air attack in the land of Troy for McKay’s inaugural season that ended with a 4-6 record. Future Pittsburgh Steeler draft pick QB Bill Nelsen was the leading passer, managing a meager 29 completions in 72 attempts for 446 yards and three TD passes and three interceptions.

Fortunately for Coach Coryell, his record of three conference championships in his three seasons at Whittier College and an excellent recommendation from Coach McKay at USC catapulted Don to the head of the list of coaches seeking the top job at San Diego State College.

The previous staff had closed out the 1960 season with a 1-6-1 record, was shut out four times and scored only 53 points in eight games while surrendering 207.

Enter Don Coryell, and the turbo props propelling the infancy of “Air Coryell” were warming up on the runway! Stay tuned and strap yourself in because in another decade or so, those turbos would be upgraded to jet propulsion engines which mercilessly strafed opposing defenses and gridiron turfs across the continent.

Coryell’s 12-year tenure at the helm of the Aztec’s football program, which would see him win 104 games with only 19 defeats and 2 ties and undefeated seasons in 1966, 1968 and 1969, took flight in 1961 with a resounding 7-2-1 record.

The blueprint for what was to become “Air Coryell” still was in its formative stages however as recruiting battles lost against USC and UCLA for top-notch high school running backs and offensive linemen recruits throughout southern California schools spurred Coryell and his staff in a direction that eventually led to air supremacy.

Without the ability to out recruit the Trojans and Bruins for the premier talent for Coryell’s “I” formation attack that he featured at Whittier College and at USC, Don and his staff turned their eyes to the junior college ranks and decided to focus on the passing game because “lots of kids in southern California were throwing and catching the ball and there was a deep supply of QBs and receivers.”

Winging the ball up and down the Aztec Bowl were highly touted junior college transfer QBs destined to be future NFL signal callers like Don Horn, Jesse Freitas, Dennis Shaw and future NFL MVP Brian Sipe.

Complimented by a stable of transfer receivers led by NFL bound Isaac Curtis, Gary Garrison and Haven Moses the Aztecs soared from obscurity to national prominence.

It also did not hurt that these talented players were tutored by the likes of future NFL coaches named John Madden, Joe Gibbs, Ernie Zampese, Al Saunders, Jim Hanifan and Rod Dowhower.

With a passing game featuring precise seam and crease throws coupled with vertical balls to outside wide outs who blew by opposing secondarys, it was only a matter of time before the NFL came calling.

So, Coryell and many of his staff packed their bags and were off to St. Louis for a five-year stint with the hapless Cardinals which had not been to the play-offs in 26 years, and then it was as the Chicago Cardinals.

With Jim Hart under center and TE Jackie Smith, WR Mel Gray and all-purpose yardage record setting RB Terry Metcalf on the receiving end, the Cardiac Cards posted three consecutive years of double digit victories and two division titles.

Unfortunately and without any notice, another one of owner Bill Bidwill’s bouts of disenchantment resulted in the keys for Don and his staff not being able to unlock their office doors one Monday morning mid-1977 season, as Bidwill had the locks on all of the doors switched that Sunday night following a loss.

That unceremonious termination actually turned out to be the football gift of a lifetime for Don and his staff as he ended up taking over a 1-4 Charger team in late September 1978, and closed out that campaign with eight wins in the ‘Bolts final 11 games.

And as they say, the rest is history as Coach Coryell unleashed an unparalleled explosive aerial attack directed by a bird-legged former Oregon Duck QB named Dan Fouts.

With Fouts winging balls on Coryell’s pass play designs that pierced defensive seams with “Bang 8” throws and tortured opposing underneath coverages with exotic read screens, “Air Coryell” posted three straight division titles in 1979, 1980 and 1981 and led the league in passing six consecutive years (1978-1983).

It did not hurt that on the receiving end of these throws were future NFL Hall of Famers in WR Charlie Joiner and TE Kellen Winslow in addition to sterling wide outs John Jefferson and Wes Chandler.

To add insult to injury, complimentary players attacking from the backfield were James Brooks, record-setting Lionel “Little Train” James and Chuck Muncie. James broke Terry Metcalf’s record in 1985 for receiving yards by a running back with 1,027.

Coach Coryell wrapped up an illustrious career as the first coach ever to win more than 100 games at both the collegiate and professional level with records of 127-24-3 in the college ranks and 114-89-1 with the Cards and Chargers.

The only knock against Coryell coached pro teams was that despite scoring 42 or 49 points in a game, his defense was liable to surrender 49 or 52.

Opposing defensive coordinators did not get much sleep during Charger week as they definitely did not look forward to preparing schemes in attempts to thwart Fouts’ aerial assaults, and as Al Davis used to say when he walked into the offensive coaches’ room during Charger week, “just don’t quit scoring because we probably will need every point you can muster.” And more often than not, he was correct!

While Don’s “Air Coryell” was soaring and strafing opposing defenses with Dan Fouts pulling the trigger, a franchise under new ownership up in the Bay Area was in the throes of two dysfunctional seasons.

Edward DeBartolo, Sr. had purchased the San Francisco 49ers in the spring of 1977 and turned over operations to Eddie Jr. A 0-4 start was salvaged to a small degree with a 5-9 finish, but any optimism for a better record in 1978 quickly was dashed with a second consecutive year of opening with a 0-4 mark.

A nine-game losing streak fueled by a NFL record 63 turnovers ended a dismal 2-14 season in which the Niners also were dead last in the league in scoring with 219 points.

Fortunately for the DeBartolo’s, a mere 40 miles south down the 101 and 280 freeways was a former NFL assistant who successfully was reviving the football fortunes at Stanford University.

Bill Walsh had just wrapped up year two with an 8-4 record and an upset victory over 11th ranked Georgia in the Bluebonnet Bowl and was riding high down on “The Farm” as his record was a nice follow up to a 9-3 mark and a Sun Bowl appearance following his inaugural campaign.

A California native who had played at San Jose State and later served as an assistant at both California and Stanford from 1960-1965, Walsh was eager to take another stab at coaching in the NFL, this time as the head coach.

As the running backs coach with the Oakland Raiders in 1966, Bill was exposed to the vertical passing philosophy of Al Davis’ Raiders, and after the 1967 season where he served as head coach of the San Jose Apaches of the Continental Football League, Bill packed his bags and headed to the midwest as the wide receiver coach for the expansion Cincinnati Bengals, whose owner and head coach was none other than Paul Brown, a stern taskmaster and the former winning head coach of the Cleveland Browns.

A 3-11 record for a first-year expansion team was not unexpected, and a benefit resulted in a first round draft pick of a strong-arm local college QB named Greg Cook.

The Bengals opened with three consecutive wins, but a promising 1969 season came to a sudden halt when Cook suffered a severe throwing shoulder injury vs. the Chiefs, and, unfortunately, it was a career ending injury.

Paul Brown engineered a trade with the Chicago Bears for QB Virgil Carter, but little did Bill know that this 6-1 QB who was mobile and very accurate but lacked a “strong arm” would lead to the birth of a new Bill Walsh that would impact the NFL for decades to come.

A thorough off-season evaluation of Carter’s skill set led Walsh to modifying his vertical passing game to a horizontal passing game, relying on quick and short throws augmented with some designed pocket movement concepts.

As a result, Carter led the league in 1971 with a completion percentage just shy of 70%.

The timing for the quick and short passing games Bill installed required precise footwork by the QB so that the ball was in the air even before the final break of the receiver.

Based upon the routes called, Bill had a variety of 3-step drops for the quick game and a multitude of 5-step drops for the short and intermediate pass offense.

Brown retired after the 1975 season, and when he named Bill Johnson as head coach, Walsh surfaced in San Diego as Tommy Prothro’s offensive coordinator for a single season before taking the head job at Stanford.

The refinement of his passing game concepts continued during these stints and all of the pieces finally came together with the union of Joe Montana and wide receivers Jerry Rice, John Taylor, the late Dwight Clark and running back Roger Craig.

Montana was gifted with footwork that worked magic with all of Bill’s drops, and though he did not have a big arm, his timing, accuracy and the ability to throw a very catchable ball methodically carved up opposing defenses.

Bill’s masterful play calling was high-lighted by the notoriety of his scripting of the first 10 or 15 plays, fashionably probing the defense like the opponent against whom he boxed in his youth and in the service, often running a play or displaying a formation, a motion or a shift to get a peek at the defense’s response so he could come back in a later series to run his knock-out play.

Six division titles and victories in Super Bowls XVI, XIX and XXIII contributed to 102 wins and a national media fascination with the intricacies of the popularized “West Coast Offense.”

They say that imitation is the greatest form of flattery, and the NFL was no exception as by the late 1980s there were at least 14 other franchises whose coordinators were running some version of Bill’s offense.

His offensive assistants Mike Holmgren, Jim Fassel, Sam Wyche, Dennis Green and Paul Hackett were able to achieve success with other clubs as they featured many of the concepts that were refined by Walsh’s mentoring.

As late as the 1998 season one half of active NFL coaches could be traced to Bill Walsh and Tom Landry, and of those 15, four, in addition to Walsh and Landry, had coached a Super Bowl winning team.

Although Sid, Don and Bill have since passed, there are many former players and coaches who regale in relating their experiences under these three great innovators who also were outstanding teachers. Coaches in today’s game still are employing many of the concepts first brought to the gridiron some 60 years ago, benefitted by an encyclopedic internet featuring video and copies of playbooks.

To be the proverbial fly on the wall to listen to their conversations and to watch them as they work their concepts on the white board truly would be pigskin heaven.

Ensure you follow on X (Twitter) @HondoCarpenter and IG @HondoSr and never miss another breaking news story again.

Please let us know your thoughts when you like our Facebook page WHEN YOU CLICK RIGHT HERE.