Lou Henson, 88: An Illini Legend for Far More than Basketball Success

Lou Henson was so much more than an immensely successful basketball coach. He was the beloved face of the Illinois program, the face of Illini athletics. And he will remain that for years to come.

In retirement, his stature grew and grew. Because Henson, who died at 88 on Saturday, was a very genuine man who walked on the sunny side of life, especially in retirement.

His twilight years stand in stark contrast to his celebrated rival, Bob Knight. Before Knight finally returned to Indiana’s Assembly Hall earlier this year, obviously in poor health, the combative Indiana legend carried a grudge against IU that extended far beyond the limits of reason.

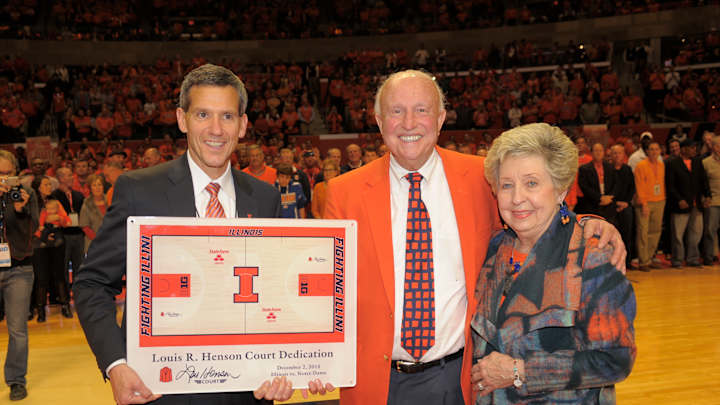

Henson, on the other hand, returned regularly to Illinois’ Assembly Hall, wearing his signature orange blazer and sitting among adoring students and fans who never tired of seeing Lou and his wonderful wife, Mary, another fine ambassador of Illini athletics.

Different situations, you might say. Knight was fired. Henson retired.

But maybe not as different at you think.

It was pretty clear that Lou really didn’t want to retire as Illini coach in 1996. The key evidence: He returned to coach at New Mexico State in 1997 and stayed nearly eight seasons, until ill health made it necessary for him to step down.

But I believe that despite wanting to keep coaching at Illinois, Henson agreed to go along with athletic director Ron Guenther’s decision that it was time for Henson to retire. Because unlike Knight, he had the maturity to see the bigger scheme of things.

Stepping down before he was ready to stop was not an easy thing for a competitor like Henson. But that’s the kind of man Lou Henson was.

He had grown up dirt-poor in Oklahoma during the Great Depression. He had fought for everything he had accomplished in life. He had gone from obscure junior-college player to high school coach to taking New Mexico State to a Final Four with a talented guard named Jimmy Collins who would become a dedicated assistant coach.

Fighting was the trademark of his Illinois teams, who were the Fighting Illini in every sense of the word.

A former player of his once marveled to me at the way Henson’s successor, Lon Kruger, calmly outlined defensive strategy during a timeout. With Henson, it was all about intensity. ``I don’t care how you do it. Just do it,’’ he would implore after outlining the strategy.

It’s a shame that his greatest accomplishment, taking Illinois to the 1989 Final Four, was followed by a murky NCAA investigation that crushed the program’s momentum even though it failed to uncover anything substantial.

Henson was 423-224 from 1975-1996, with 12 NCAA tournament appearances, at Illinois. He was 779-413 overall, including the two stints at New Mexico State and his first job at Hardin-Simmons. When he retired, only four coaches—Knight, Dean Smith, Adolph Rupp and Jim Phelan—had won 800 games in Division I. He is still the game’s 15th winningest coach.

For all that he accomplished at Illinois, the what-if disappointments leave room to think there might have been more. With a Final Four trip at stake, the 1984 Illini lost an Elite Eight showdown to Kentucky on the Wildcats’ home floor in the days before teams were barred from enjoying that kind of home-court advantage. The 1987 first-round loss to Austin Peay also stung.

That said, Henson brought remarkable stability to a program that had been floundering before he arrived. He coached in a golden age of Big Ten basketball where he, Knight, Purdue’s Gene Keady and Iowa’s Dr. Tom Davis led a talented and fiercely competitive league.

For all of his fighting spirit, though, Henson was very much a realist in his post-game comments. In that Oklahoma accent that never left him, he did not sugarcoat his concerns. And he did not shy away from candid assessments of his players and his team’s prospects. Like my own father, Lou had grown up in the Depression.

What I also will remember, though, is the gentler side of Lou Henson.

When I started covering his team, he welcomed me to the beat. He always returned phone calls, even when there were awkward moments, including the time when he curiously was hinting strongly to recruits that Jimmy Collins would follow him as Illinois coach.

``Does your wife work outside the home?’’ he asked me, a phrasing I never forgot because it showed his respect for so many things.

When he met Liz, he used the same phrase. Which she also appreciated for all of its levels.

And Lou’s wife, Mary is such a joy, was such a perfect complement to her husband the coach. So gracious, and so interested and caring. I remember sitting with her on the bleachers at a modest arena in San Juan, Puerto Rico, and listening to her tell the story of how they met. They were working summer jobs at a cannery, if I remember it right.

Years later, long after Lou had retired, I called their home in Las Cruces, N.M., where they lived when they weren’t making their extended returns to Champaign.

I just needed a quick comment from him. Lou was out playing cards with some friends. But Mary and I chatted a long time, mostly about New Mexico. I had worked in Albuquerque briefly and mentioned that we were thinking we might retire to Albuquerque/Santa Fe when the time came. She gave me the pitch for their beloved Las Cruces.

So genuine. So engaged. That was Lou and Mary. They had such a great run at Illinois—and everywhere they went.

My heart goes out to Mary and all of Lou’s loved ones and friends. But what a great run. What a great life.