Man for All Seasons: UW's Ralph Winters (1942-2020) Positioned Himself for Success

Ralph Winters will always be remembered as one of the more unique football players to come through the University of Washington, choosing a career path few others could rightly envision.

He went from quarterback to defensive end and offensive end to safety, switching jersey numbers from 12 to 97 to 12.

Even for the 1960s, when single-platoon football required players to go both ways and substitutions were limited, Winters -- a tough guy raised on a 1,100-acre cattle ranch -- was a rarity for the Husky program.

"I want to play any way I can get on the field," Winters told Seattle Times sports columnist Georg N. Meyers in 1965.

Winters, who was 77 when he died on April 4 in Peoria, Arizona, due to complications from Alzheimer's disease, spent his freshman and redshirt freshman seasons as a reserve quarterback, becoming the varsity backup at times in practice.

Spotting an opening for playing time, he emerged as a starting two-way end in 1963, a Rose Bowl year for the Huskies. After two-platoon football was made a college staple the following season, he shifted to safety and started as a junior and a senior.

He finished his versatile college career with the following stat line: 8 receptions for 116 yards and 2 touchdowns, 6 interceptions and 2 punt returns for 23 yards.

"I think the most valuable thing that happened to me as a defensive back was playing quarterback and end," Winters explained. "I knew what was going through a quarterback's mind when he is looking around with the ball in his hand. And I know the patterns the ends are taught to run."

Raised on a 1,100-acre cattle ranch in White Swan, Washington, Winters was the younger brother of quarterback Bob Winters, who became one of the nation's leading passers for Utah State in 1957.

Ralph Winters transferred from White Swan High School to the much larger Eisenhower High in Yakima for his senior year, urged to do so by his father Reuben to draw maximum recruiting attention.

Bill Douglas, his good friend, a fellow quarterback and also raised on a farm, tried hard to convince him instead to enroll at his nearby Wapato High.

In the end, the two of them ended up playing a basketball game against each other, with Wapato winning and advancing to the state tournament when Winters fouled out late.

"Ralph was really a good competitor under pressure," Douglas said. "He was one of my best friends. I really loved the guy."

Winters initially planned to play for Washington State and Douglas committed to Stanford, but each eventually changed course and accepted UW scholarship offers.

They were finally teammates, alternating as quarterbacks on the Husky freshman team with Tod Hullin. They were backups to varsity starter Pete Ohler in 1962 before Douglas became the No. 1 quarterback at midseason and flourished. Winters switched positions when it was clear his friend was well-established behind center.

"If you're not going to be the quarterback, you better come home and work the farm," Reuben Winters told his son, who resisted that idea.

The following year, Douglas and Winters shared in the Rose Bowl together when Washington won the conference championship and earned the right to play Illinois on New Year's Day. Douglas was the starting quarterback and Ralph a two-way end.

The Huskies were leading 7-0 when Douglas suffered a terrible knee injury and was taken off the field on a stretcher, and they wound up losing 17-7.

Earlier that season, Douglas threw a 28-yard touchdown pass to Winters in a 34-7 victory over Oregon State in Seattle and a 21-yard scoring pass to Ralph in a 22-7 win over USC at Husky Stadium.

In 1964, Winters' crowning moment at Husky came when he intercepted two passes to help the Huskies rally from a 13-0 deficit in the fourth quarter to upset USC 14-13 in Los Angeles. Both were huge plays. His first pass theft came in the end zone, the second interception at the UW 25.

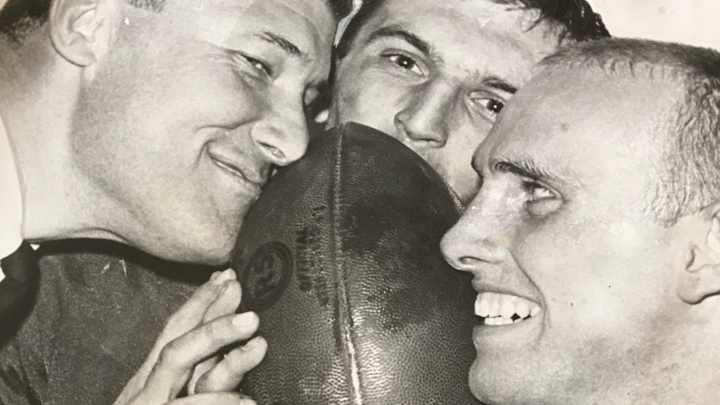

Winters served as a Husky co-captain with Ron Medved in 1965. He preserved a 28-21 victory over Oregon State with a last-minute interception at the UW 4. It was a moment the heady defensive back celebrated following the game with Husky coach Jim Owens and fellow back Ron Medved, as shown in the accompanying photo.

Ralph Winters moved from quarterback to two-way end.

Bill Douglas and Ralph Winters were friends who both grew up on farms.

Ralph Winters (97) had two interceptions in 1964 upset.

Ralph Winters and fellow back Ron Medved captained the Huskies as seniors.

Initially a quarterback, Ralph Winters made interesting position change.

Ralph Winters was a standout in upset of USC.

The week before, Winters was the Husky defensive back who was victimized when UCLA coach Tommy Prothro used what he called the "Z-streak," a play that Owens would always consider bush league.

With the UW in its defensive huddle, Bruins wide receiver Dick Witcher slyly snuck over to the sideline but didn't leave the field. Unguarded when the ball was snapped, he caught a 60-yard pass from Gary Beban and went in untouched for the winning score in a 28-24 game in Los Angeles.

"Just as the play started, I saw him," Winters said. "I took off. It was no use."

The safety had a tryout with the then-AFL's Denver Broncos, similar to his brother Bob, who went to camp with the Pittsburgh Steelers. Ralph later played with the Seattle Rangers semi-pro team.

Post-football, he became a vice principal and assistant football coach at Seattle Preparatory School and as football coach and athletic director at Eastside Catholic High School, and he later sold real estate.

Always, he was a fearless, aggressive player, which might have contributed to his health issues. He had struggled with Alzheimer's for the past year and moved into a memory facility in Arizona.

His daughter, Sandra Winters, said the family would donate her father's brain to Boston University to be used for head-trauma research.

"As much hitting as we did, with Ralph doing it through high school and college, you have to wonder if it wasn't from too many concussions," Douglas said.

Dan Raley has worked for the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Atlanta Journal-Constitution and Fairbanks Daily News-Miner, as well as for MSN.com and Boeing, the latter as a global aerospace writer. His sportswriting career spans four decades and he's covered University of Washington football and basketball during much of that time. In a working capacity, he's been to the Super Bowl, the NBA Finals, the MLB playoffs, the Masters, the U.S. Open, the PGA Championship and countless Final Fours and bowl games.