'Indy as it should be' -- Indy 500 qualifying brings back memories of how it once was

INDIANAPOLIS – I’m so old school, I miss much of what Indianapolis Motor Speedway used to be.

The warbling of turbocharged Offenhauser engines echoing off the main straight grandstands is a sound I wish everyone could have heard. When the green and white barn doors in the garage area swung open, you could easily imagine cars of the 1920s, 30s, 40s, 50s, 60s and 70s sitting inside.

There was a grassy strip between pit road and the main straight where race crews held sign boards to relay information to drivers, and that also was where drivers lounged in the sun during a break in the action on a warm May day.

As much as this place, and this race, reeks of tradition and history, a lot has changed to sterilize the effect.

The garage area is a continent of concrete. Pit road is pavement and concrete from wall to wall. Sign boards are in museums and antique shops.

Progress is a necessary thing, especially in a sport like this, and I understand that things simply can’t be the way they were. But the cost is the loss of what drew many of us to it, particularly at this speedway, magnificent as it still is.

I wish everyone could sense what IMS was like 49 years ago when I first stepped onto these grounds, just as those 49 years ago probably wished I could have experienced what they felt when they were first-timers.

It wasn’t perfect, but it was Indy. And I miss so much of it.

But what occurred Saturday during the first day of qualifying for next Sunday’s Indianapolis 500 captured the stress, exhilaration, frustration and drama that has been part of this race forever. It was Indy as it should be.

There was a record 84 four-lap qualifying attempts, and the action was nonstop right up to the moment the session closed at 5:50 p.m.

Indy’s qualifying format has been folded and manipulated over the years, to the point that it’s not recognizable from what it used to be – a one-time four-day process that was a happening on the first day, drawing 250,000 spectators, and a nice dose of intensity in the final moments of Day 4.

In between, though, could be hours of dead track time as teams waited for late-afternoon conditions conducive to better speed.

Those were the years when more than 100 entered the race and as many went home as attempted to qualify.

Modern-day IndyCar racing doesn’t have that; it’s been a stretch to get 33 entries some years, and 34 this year meant one wouldn’t make it.

On the surface, that doesn’t sound too dramatic, but the format created six hours of action Saturday with several drivers making multiple attempts to either crack the top 12, which qualified them for Sunday’s run for the pole.

Or to avoid the bottom four, which meant they would run again Sunday to see who wins the last three sports, and who doesn’t make the race.

There was drama, stress and intrigue, and it lasted all day.

The current two-day qualifying process isn’t easy for the average sports fan to understand, but it works.

Basically, the fastest 30 on Saturday secured a place in the 500. The top 12 will come back Sunday to run two sessions that determine the pole winner – one session narrowing it to the top six, then a final shootout to decide the pole.

The slowest four also will qualify again Sunday to set the 31st , 32nd and 33rd starting spots, with the slowest entry -- the 34th -- being the odd driver out who will unfortunately miss the race.

And, oh, is there drama in that. The final four includes three from the four-car Rahal Letterman Lanigan team – Lundgaard, Jack Harvey and Graham Rahal. The other is rookie Sting Ray Robb with Dale Coyne Racing.

So far, the only Rahal driver to make it out of Saturday was Katherine Legge. It’s possible the other three will make it Sunday, although Graham Rahal’s best speed in four attempts Saturday ranked last at 228.526 mph.

It brought back some tough memories from 30 years ago when Rahal’s dad, Bobby, missed the 500.

At the top, Arrow McLaren and Chip Ganassi Racing each put all four of their cars in the top 12.

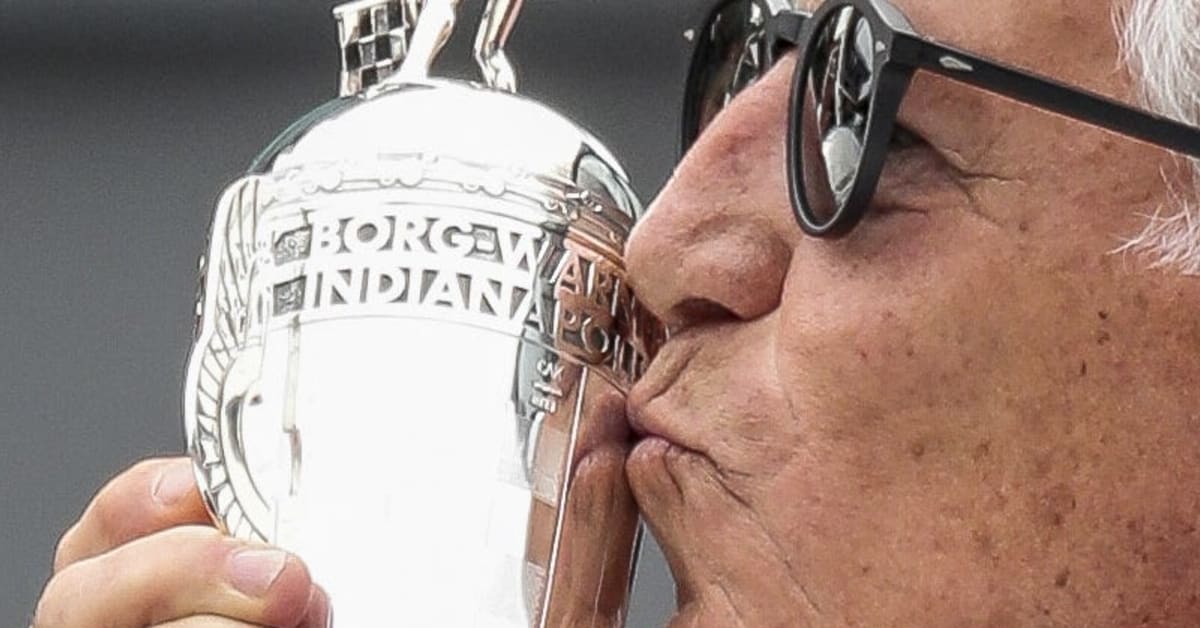

McLaren’s Felix Rosenqvist led all qualifiers at 233.947 mph with teammates Alexander Rossi second, Tony Kanaan sixth and Pato O’Ward eighth. From the Ganassi camp, Alex Palou was third Scott Dixon fifth, Takuma Sato seventh and defending 500 winner Marcus Ericsson 10th .

A.J. Foyt Racing showed a crowd-pleasing resurgence with Santino Ferrucci ninth and rookie Benjamin Pedersen 11 th .

Team Penske’s lack of dominance at Indy the past three years showed itself again, with only Will Power getting into the top 12. Josef Newgarden boldly pulled his previous qualifying speed in the final minutes attempting to crack the top 12, but he improved only one position and will start 17th in the 500. Scott McLaughlin will start 14th .

There were feel-good stories aplenty:

* Legge is back in the 500 for the first time since 2013 and, qualifying 30 th , will be the highest-starting driver from the Rahal team.

* Rookie R.C. Enerson, seemingly everyone’s early pick to miss the race with the small-budget Abel Motorsports team, qualified 29th and will take the green flag next Sunday along with 32 of his rivals.

* And Callum Ilott, driving a replacement chassis after his Juncos Hollinger Racing team parked his evil-handling original following Friday’s practice, made a late run to land the 28th starting spot after earlier attempts made it seem he had no chance. It was a sweet result for a team that worked through the night to get the car ready.

That’s what happens at Indy. Drama comes in many forms, always has, and the current product is as fast and compelling as ever. When qualifying wraps up Sunday, it’s possible only 3 mph will separate the fastest from the slowest qualifiers.

That’s phenomenal.

Now, if they can bring back those old barn doors to the garages and put some grass alongside pit road, those of us who’ve been here awhile will exhale with a satisfying sense of nostalgia.