On This Day in 1991, the A's Rickey Henderson Moved Past Lou Brock With Steal No. 939

Some bits of Major League Baseball history come seemingly out of nowhere – no-hitters and four-homer games come to mind.

Some bits come with drum rolls. It’s into that second category that Rickey Henderson’s move into first place on the all-time stolen bases charts falls. It was on this day in 1991 that Henderson stood at third base in the Oakland Coliseum after his 939 steal, the new – and possibly forever – champ.

The 1991 season began with 936 steals on Henderson’s ledger. There had been some buildup in late September that he might overtake Brock at the end of the 1990 season. Henderson only had five steals that August, but he swiped 13 bases in September with the A’s in a push for the post-season and came up just short, getting thrown out on steal attempts twice in the last four days of the 1990 season.

On this date in 1991, Rickey became the greatest of all time. #CheersToHistory pic.twitter.com/gmIG9oASlt

— Oakland A's (@Athletics) May 1, 2020

Steal No. 937 came on opening day, April 9, with a huge throng of national media in the Coliseum to record the event. They didn’t want to miss out on being on hand for the main event, and Henderson had a history of stealing bases in bunches. On 11 different occasions in 1990 he’d stolen two or more bases. Henderson singled in the first inning and came around to score on a Terry Steinbach RBI single en route to a 7-2 A’s win over Twins’ Hall of Fame starter Jack Morris.

And then everything was put on hold. Henderson only reached base once in the next two games, didn’t steal in either game, then went on the disabled list with a minor injury. Now all those photographers, writers and camera crews could only wait. Some went home; some waited around.

Henderson was back playing on April 27, stole the record-tying 938 base on April 28, taking off for second base moments after Angels’ right-handed reliever Jeff Robinson in the sixth inning. He would score the sixth run in a 7-3 A’s win.

He didn’t try to steal on April 30 in the first game of a series against the Yankees, but in the first inning on May 1, New York catcher Matt Nokes was able to throw out Henderson at second base on a steal try.

Henderson gave it another try in the fourth inning, this time at second base after reaching on an error and taking second on a Dave Henderson single. Rickey took off and this time Nokes had no answer. A typical Henderson head-first slide saw him came up with No. 939. Yankees’ third baseman Randy Velarde slapped on a tag, but it was too late. Yankees’ pitcher Tim Leary stepped off the mound; it was clear it would be a bit before he’d be throwing another pitch.

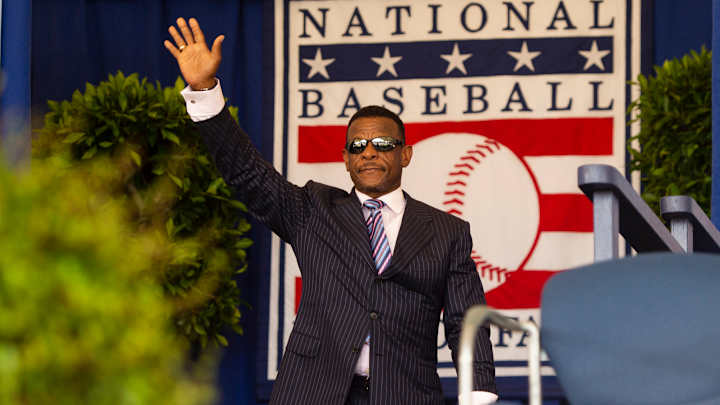

Henderson pulled the base up and waved it over his head, doing a 360-degree rotation to show it to the Wednesday afternoon crowd of 36,139. The game came to a stop and A’s longtime equipment manager Frank Ciensczyk brought out a replacement base and Henderson’s mother, Bobbie, who’d named her son after singer Ricky Nelson, joined him on the field.

So, too, did Brock, who’d been among those left to spend extended time in the Bay Area when Henderson came up hurting in April. Both Brock and Bobbie Henderson gave the new Man of Steal big hugs.

Talking to the crowd, Rickey said “It took a long time, huh?” He then went on to thank then-Milwaukee manager Tom Trebelhorn, who’d been a minor league manager in the A’s system when Henderson was coming up. He had words of praise, too, for former A’s manager Billy Martin, who’d let Henderson run almost at will in the early 1980s, including his record-setting total of 130 steals in 1982.

Clearly feeling good about what he’d done, Henderson finished up saying “Lou Brock was a great base stealer, but today I am the greatest of all time.”

There were many quick to fault Henderson for a lack of proper modesty, while other took it more as a statement of fact.

Henderson was, in fact, a huge Lou Brock fan. In the off season shortly after arriving on the scene in Oakland, Henderson called Brock, then went to visit him in St. Louis to talk about baseball and stealing bases. They’d kept in touch. Henderson went so far to hire Brock’s agent, Richie Bry, as his own agent.

Henderson and Brock were prepared for 939. In the buildup toward the record, Brock helped Henderson sketch out some thoughts for what he could say when he got the big one. In the heat of the moment, Henderson forgot about those talking points, which remained in his pocket.

Even before 939, Rickey had a history in big moments. On Aug. 22, 1989, the A’s were on their way to a World Series title. On that evening in Arlington, Texas, however, Rangers’ starter Nolan Ryan was six Ks away from becoming the first pitcher with 5,000 strikeouts. Privately most of the A’s dreaded the thought of being No. 5,000. Not Henderson, who already was completely secure in his spot in MLB history.

Leading off the fifth inning, Henderson ran the count full against Ryan, fouled off a couple of pitches, then went down swinging for No. 5,000, chasing a low Ryan heater. After the game, Henderson was all smiles, in part because the A’s beat Ryan 2-0 behind Bob Welch and Dennis Eckersley. Being the 5,000 strikeout bothered Henderson not at all, saying “it was an honor to be the 5,000.

He then went on to quote a former teammate, saying “As Davey Lopes says, `If he ain’t struck you out, you ain’t nobody.’”

Once the 939 steal was in the books, the game went on. Harold Baines, who’d been at the plate for the steal, stepped back into the batter’s box and delivered an RBI single, bringing Henderson home for a 4-2 Oakland lead en route to a 7-4 A’s win.

And that’s the backstory. The three 1991 steals that got Henderson up to and past Brock all led to A’s runs. All three led to A’s wins. The runs scored and the wins collected define Rickey Henderson as much or more than the steals.

Henderson was part of the A’s resurgence under Martin in the BillyBall era. When he was traded to the Yankees before the 1995 season, he became the best player on a New York team that won 97 games.

When he was traded back to the A’s in 1989, he refueled a team that went on to win the World Series.

When was traded to the Blue Jays in 1993, he earned another World Series ring. The Padres picked him up for 1996 and won the NL West for the first time in a dozen years. His 1997 season with the Angels gave that franchise its first 80-plus-win season in six years.

His 1999 stop with the Mets fell just two wins shy of the World Series. A year later he joined the Mariners and helped the to what was at that point their winningest (91) season and, again, he wound up two games short of another World Series appearance.

Henderson, who ended with 1,406 career steals, will always be remembered first for his stolen bases, although perhaps more attention should have been paid to the fact that he scored more runs, 2,295, than anyone in baseball history.

But for today, it’s cool to think about all those steals.

Follow Athletics insider John Hickey on Twitter: @JHickey3

Click the "follow" button in the top right corner to join the conversation on Inside the Athletics on SI. Access and comment on featured stories and start your own conversations and post external links on our community page.