Upcoming game with ASU reminder little known Razorback changed basketball history

In this story:

(Note: This story originally ran in July and includes quotes from an article originally written by Kent Smith back on Jan. 14, 2024)

FAYETTEVILLE, Ark. — Everyone knew back in the days of Frank Broyles as athletics director at Arkansas there was a strict policy against playing Arkansas State.

His philosophy was there was nothing to be gained and everything to lose should that ever happen, which might seem archaic to modern day fans on the brink of watching the two programs playin football.

It turns out, when legendary Arkansas coach Nolan Richardson found himself in an NIT game against Nelson's Catalina's Indians in his second season (before they were renamed Red Wolves), there really was everything to lose.

If his Razorbacks came up short, he was going to be fired. If it weren't for a little known guard mostly lost to Arkansas basketball history by the name of Cannon Whitby, that's exactly what would have happened.

Richardson would have lost out on his gamble to become the man who followed Eddie Sutton after bringing in a single recruiting class. There would have been no national championship, nor decade of dominance in the 90s that set the table for John Calipari at Arkansas nearly 30 years after Richardson's dramatic departure.

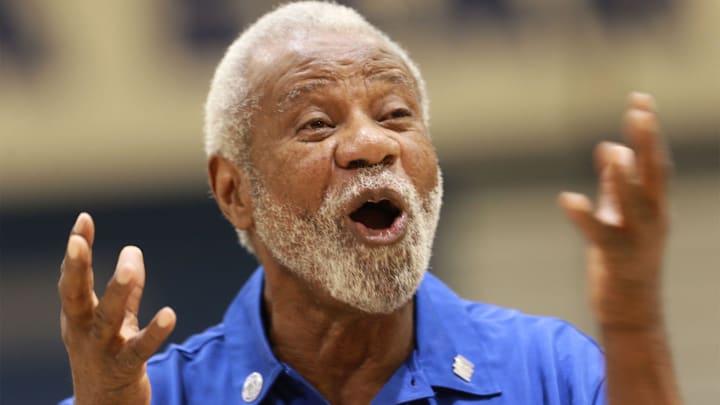

The high emotions of that night were captured in a post by Channel 7's Steve Sullivan just shy of two months before the Razorbacks get set to take on Arkansas State for the first time in football. The raw emotion in the video encapsulates what was a long time of extreme emotional strain on the Richardson family, and here is the story behind it.

A blast from the past. KATV archives. Nolan on his coaches show with Paul Eells in 1987 talking about

— Steve Sullivan (@sully7777) July 22, 2025

overtime NIT win over Arkansas St. pic.twitter.com/qKplnKCkWn

Richardson's been on both sides of the coin as a coach trying to follow a legend. He replaced the Godfather of modern Arkansas basketball in Eddie Sutton after he spent the the 70s and early 80s turning the Razorbacks into a national power.

Richardson also tried to help Stan Heath as he struggled to follow the national championship winning coach in the early 2000s after Richardson turned Arkansas into a rabid basketball machine. Needless to say, he has experience on the matter perhaps no one else in the history of college sports has.

"Anyone that takes that job that's got a job gotta be out of his mind because you don't follow the guy that is the guy," Richardson said on 103.7 The Buzz shortly after Alabama coach Nick Saban announced his retirement. "You know, you may follow the guy after four or five guys have gone through there because there's no question of his records and the things he has done. Who can duplicate that?"

Of course, a much younger Richardson wasn't willing to take that advice when to jumped from Tulsa to Arkansas back in the mid-1980s. Nearly everything about the Razorbacks job screamed to not take it.

Not only was Richardson stepping into Sutton's shoes, but he did so as the first African-American head coach in a state that had struggled mightily with the idea of racial tolerance. Still, there was enough there to entice Richardson despite the potential pitfalls.

"I think any job that you're going to go through is either going to look a little bit better with some things in your favor that you're looking for," Richardson said. "There's no question, I was pretty happy and we were doing a pretty good job at University of Tulsa. But you know, we didn't have a gym on the campus. We had so many shortcomings that we were able to get over. But University of Arkansas you had fans that came when it snowed and you're not supposed to be on the highway. We just couldn't attract that. And I enjoyed the fact that Eddie had already built it into a tremendous basketball program."

Still, the advice he shared in his more wise years almost proved to be prophetic. Sutton ran a slow, plodding half-court style of basketball, which meant players wouldn't be a good fit for Richardson's frantic high-speed style.

He also found out a few weeks before he took that job that his daughter, Yvonne, would spend her time in her new home in Fayetteville battling Leukemia. Combined, it was the perfect storm of negative factors.

"I couldn't enjoy anything to be honest with you," Richardson said. "I enjoyed getting the job, but then she was sick that same year. Bringing her away from that, I had so many other things on my mind. University basketball was not one of the things that were on my mind at the time, to be honest with you."

The two years Yvonne was sick almost ended Richardson's stint at Arkansas before he could get his feet under him. The transition to his style of play was brutal.

His 12-16 opening record was the Razorbacks' first losing season since 1973 and was a 10-game drop from Sutton's final year. The following season, with a handful of players who better fit his system, Richardson had Arkansas winning again, just not enough to return to the NCAA Tournament.

Still, the Hogs were in the NIT, which was progress, and should have been a blessing, but it wasn't. In the midst of dealing with the death of his daughter, who had lost her fight with leukemia about 10 weeks earlier, Richardson faced an ultimatum in regard to his opening game of the NIT.

"I can go back to my [second] year," Richardson said. "I was threatened to be dismissed if I didn't beat Arkansas State. There I was dealing with a sick daughter. You know, there's a lot of pressure a coach goes under without any fans knowing anything what's going on at all. Closed doors."

Richardson came as close as possible to becoming the footnote guy who followed the guy. The Razorbacks trailed ASU by 21 points, 51-30, midway through the second half before Ron Heury and Cannon Whitby's late game heroics forced overtime, allowing the Hogs to escape with a 67-64 win and their head coach still at the helm.

Huery, who was the heart and leader of the team, played as one might expect with the chips down. He was everywhere defensively and hit big shots left and right.

However, it was Whitby who brought the extra game to the moment. Known as a 3-point specialist, he indeed knocked down multiple big threes, including one from way beyond the arc.

However, his extra effort on defense and keen eye for passing lanes that wasn't typically on display came into play. He was a disruptor, which, at times, set him up for spectacular passes to the big man, Mario Credit, inside for quick scores.

Perhaps the closest equivalent to making people understand the elevation in game would be if former Arkansas guard Joseph Pinion would have had a huge game with everything on the line. Suddenly he's making all the defensive plays he could possibly make, he's hot with his shooting, and his eye as a point guard is seeing every available passing lane for prime scoring opportunities.

Whitby was more established as a player than Pinion, but that at least brings things into as much perspective as it can be with today's fans. If he doesn't blow up and have the game of his life, then the pitfall that is playing Arkansas State sinks the future of Razorbacks basketball.

There's no Rollin' with Nolan, no 40 Minutes of Hell, no national championship, likely no Bud Walton Arena and certainly no John Calipari riding in on his horse looking to restore the palace to its former glory.

Arkansas owes Whitby a debt of gratitude. He, along with the efforts of Huery, saved the program that day.

HOGS FEED:

Kent Smith has been in the world of media and film for nearly 30 years. From Nolan Richardson's final seasons, former Razorback quarterback Clint Stoerner trying to throw to anyone and anything in the blazing heat of Cowboys training camp in Wichita Falls, the first high school and college games after 9/11, to Troy Aikman's retirement and Alex Rodriguez's signing of his quarter billion dollar contract, Smith has been there to report on some of the region's biggest moments.