Tad Stryker: NIL Liberalization Will Backfire

A college head coach becoming an NFL head coach cannot truly be considered to be unexpected. Many have made the transition with varying degrees of success. Jim Harbaugh has done it twice now. Nick Saban did it, as did Pete Carroll, Barry Switzer, John McKay and Matt Rhule. Half a century ago there were rumors of Nebraska's Bob Devaney making the jump, though thankfully, he never did.

But the case of Jeff Hafley leaving his role as head coach at Boston College last week to take what many would consider a demotion as the Green Bay Packers’ defensive coordinator has a different feel to it. Apparently Hafley wants to spend most of his time actually coaching football. That’s something he decided he wasn’t able to do, even at one of the least pressure-packed places in major college football, at a hockey school in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts, one of the most marginal football programs in the Atlantic Coast Conference, the least influential Power Five football league.

This is the latest ripple effect caused by well-meaning state legislators around the nation who rushed poorly conceived NIL legislation through their statehouses, thinking they were helping college football become more equitable, but instead, are making the rich richer and the poor poorer. NIL as it currently exists, in its untamed “Wild West” state, will tend to help the crème de la crème, and especially the well-bankrolled athletic departments like Nebraska’s that are 100 percent committed to big-boy football, but will ultimately work against the good all-around athlete who wants to represent his mid-major college in football while studying to become a dentist or architect or biologist. That sort of student-athlete will have fewer opportunities in college football over the next couple of decades unless NIL rules are tamed down.

However, that doesn’t appear to be the direction things are heading, especially if the State of Tennessee, along with neighboring Virginia, succeeds in its lawsuit against the NCAA, which would double down on the current “Wild West” mentality of the sport. The suit challenges the NCAA’s NIL guidelines and essentially seeks to enshrine bald-faced “highest bidder” recruiting into law. And combined with an equally unregulated transfer portal, it will eventually reduce schools like Iowa State, Oregon State, and even 1990 national champion Georgia Tech and 1999 runner-up Virginia Tech, to mid-major status.

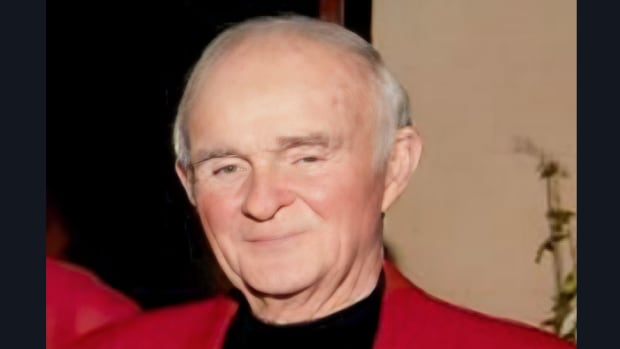

Guys like former Nebraska defensive coordinator Charlie McBride were certainly right when they said that NIL means “Now It’s Legal.” In his weekly appearances on Hail Varsity Radio, McBride occasionally laments that fewer and fewer people are taking the “student” side of student-athlete seriously these days.

More than 90 percent of NCAA athletes do not ultimately earn a living as professional athletes. The rush to NIL expansion will prove shortsighted, even if it turns out to be legal. In a misguided effort to achieve fairness, it’s instead going to exacerbate a trend that’s already problematic — luring teenagers (even at SEC and Big Ten schools) into thinking they’ll make their fortune playing sports, with no substantial backup plan in mind. A small percentage will make it big. A larger percentage will get there, then fritter away the millions they earn. A majority will never make it to the NFL, and only the ones who planned wisely will establish a solid financial future. I wonder about the fate of those who don’t plan well.

If the Tennessee-Virginia lawsuit succeeds, it will legitimize buying players for college football programs. It will encourage tampering, so increasing numbers of those players likely will jump from school to school, year by year, for a higher price. This is not the legislation’s original intent, which was to remedy the exploitation of college football players who were unable to collect payments for the use of their own name, image and likeness on college football video games and related software, or to allow college players who have attracted a following by their play on the field to capitalize by endorsing products or services. The local businesses that got burned by forking over NIL money for endorsements to “one-and-done” players will self-regulate, but I don’t have high hopes that the NCAA or state legislators will show that much sense.

Don’t get me wrong; it makes a certain amount of sense that players who poured their blood, sweat and tears into conditioning, practice, film study and playing the games, all while drawing huge crowds to the stadium on Saturdays, should reap some sort of appropriate additional financial benefit from that, beyond the value of their scholarships. I support that sort of NIL and/or revenue sharing, assuming the shared revenue goes specifically to players in the sport that produced the profit, in proportion to their playing time. That would be fair. Not this sort, not the kind that places never-ending pressure on folks like Hafley who wanted to actually coach football, instead of courting investors. Dealing with NIL demands shouldn’t be overly demanding at a place like BC, but apparently, it is.

On Power Five teams, the head coach’s job increasingly is focused on player recruitment, and re-recruitment. One of his chief duties now is ego management, terrain that used to be occupied almost exclusively by NFL coaches. It’s another sign that college football as we knew it is swiftly changing, that the cream of the Power Five football schools are inevitably rolling toward a break from the NCAA to form a league I referred to last summer as the “NFL Lite,” a league with different objectives, rules and structures for enforcement. A league consisting of teams all-in on competing for national championships, with employees and collective bargaining instead of student-athletes and Homecoming traditions. Actually, it makes a certain amount of sense if you’re trying to set up a truly competitive playoff system.

But let’s step back and take a 30,000-foot view of college football. It’s time to debunk the myth that the vast majority of college football players perform in front of huge crowds and bring in obscene amounts of revenue for their schools. That would be true for only a portion of the young men who play for Power Five schools. That’s a relatively small percentage of all college football players in the FBS, and if you add in FCS and Division II and III schools, the percentage dwindles further. The majority of athletic departments are not flush with cash. In fact, as the richer schools continue to exert financial pressure, few schools below the Power Five level will have enough athletic revenue to sustain a robust program. At smaller schools, baseball, softball, swimming and wrestling programs will be cut to balance the budget because of the misguided movement toward “fairness.” Or just as likely, some of those smaller schools will simply cut football and try to make a go of it with their remaining programs.

Let’s hope those dystopian days are decades away, at least. And as for the NFL Lite, we’re not there yet, are we? And even if we were, if Boston College thinks it has a snowball’s chance in hell at securing a spot, it’s fooling itself, right? So why did Hafley leave?

“He wants to go coach football again in a league that is all about football," a spokesman for Hafley told ESPN’s Pete Thamel in a Jan. 31 story. "College coaching has become fundraising, NIL and recruiting your own team and transfers. There's no time to coach football anymore.”

This is not the view of some bitter old geezer at the end of his college career. No, Hafley is 44 years old, and he’s apparently sick of having to re-recruit his players every year.

Nebraska fans should be grateful for someone like Matt Rhule, who from all indications has the bandwidth to raise money while lifting expectations, developing three-star players into dependable starters and working to build a culture where his top players don’t have one eye on their next destination, which should make re-recruitment easier.

The battle for the almighty dollar illustrates reasons for the growing gap between haves and have-nots, including NIL, actual-cost-of-attendance, payment for good grades, and more. An ever-shrinking number of schools will be able to afford to be truly competitive at the highest level of college football. Nebraska will certainly be one of them thanks to recent leadership shown by Trev Alberts and Rhule. But it will come at a cost, as increasing numbers of coaches and schools decide it’s not worth the effort.