Why is it so hard to predict which college QBs will succeed in the NFL?

Mark Schofield was a terrible Division III quarterback. He threw more interceptions than touchdowns and still hears the echoes of his coach yelling at him for botching the smash concept read.

Suffice to say, Schofield did not become an NFL prospect. Instead he became a lawyer but he never really put his playing days behind him. He remained fascinated with quarterback play and in 2014 helped launch the hardcore football analysis and teaching website Inside The Pylon. Two years later — and around 15 years after graduating from law school — he was hired by Bleacher Report as a quarterback analyst. He adopted the phrase, “those who can’t do, evaluate.” And when he watches tape, he still can’t believe how easily the quarterbacks read the smash concept.

Schofield is the best of the outside world when it comes to analyzing quarterbacks. If you were only allowed to read one person’s opinions on the upcoming QB class, Schofield would be a top five pick. He takes a lawyer-like approach to picking apart the evidence with each QB and takes note of the details like nobody else. In the early days you could pick him out of the crowd at the Senior Bowl or NFL Combine because he was carrying around a big binder with all of his quarterback notes.

“When I was practicing law I liked to research and try to solve problems,” Schofield said via Zoom. “You’re looking through film and trying to find the answer to the riddle.”

The problem is that Schofield is terrible at predicting which quarterbacks will become NFL stars. He ranked Dak Prescott as QB17. He was enamored with Connor Cook and ranked Vernon Adams (who went undrafted) as QB5. Another UDFA Trevone Boykin was one slot ahead of quality NFL QB Jacoby Brissett and one slot ahead of Prescott in his rankings was Jake Rudock, who threw five NFL passes.

How could this former quarterback with a sharp mind for the game be so wrong?

“Everybody is terrible at it,” Schofield says laughing.

It’s true. The NFL drafted seven quarterbacks before Prescott and only the top two (Jared Goff, Carson Wentz) became consistent starters. In hindsight the idea of drafting Penn State’s Christian Hackenberg over a three-time Pro Bowler who is 73-41 in his career as a starter is enough to make you wonder if the NFL was taking crazy pills in 2016.

But nearly every draft follows the same pattern with quarterbacks. The following year the Chicago Bears elected not to pick the generation’s greatest quarterback Patrick Mahomes and instead went with Mitch Trubisky. In 2018 the professionals went with Baker Mayfield and Sam Darnold before superstars Josh Allen and Lamar Jackson. In 2020, every quarterback turned out to be good. In 2021, every quarterback outside of Trevor Lawrence (out of five) is not going to make it to a second contract unless the Bears shock us by keeping Justin Fields.

If you think some of Schofield’s old takes are funny, you should see the rest of the outside draft analysis world trying to predict what’s going to happen on draft night. Some had Malik Willis, a third-rounder, as the No. 2 overall pick. Some draft insiders reported the Colts were higher on Will Levis than Anthony Richardson. Well, Levis ended up in the second round.

What gives? We have more resources than ever to evaluate quarterbacks and yet even the smartest teams and the brightest analysts and the most supposedly connected reporters can’t predict what’s going to happen. Why is it so freaking hard?

“It’s the toughest transition you’ll see in sports to go from college quarterback to NFL quarterback, there are so many moving pieces and so much involved and we all get it wrong because of that,” Schofield said.

The explanation from the former lawyer cannot be boiled down to one thing but if he were making a case to be exonerated for his past draft analysis sins it would start with intangibles.

“The film is just part of it,” Schofield said. “That might be why QB evaluation is so hard — the psychological part of it is so important. You might be able to throw a football through a brick wall but if you can’t inspire those around you then that’s going to be a missing piece maybe you can make up but maybe not.”

Schofield remembers looking around the huddle when he was a struggling quarterback and seeing his teammates staring down at their cleats. He never forgot that feeling. Imagine that happening in the NFL.

“You are the de facto leader of that team and you have to act accordingly,” Schofield said. “You have to be in there on Monday working on the next gameplan and practice the right way and be able to step into a huddle as a 22 year old rookie on Day 1 and command the eyes around you even if some of the guys have been in the league for 15 years.”

Schofield points out that quarterback isn’t a snap-to-whistle position, it’s a Monday morning game planning to Sunday night podium position.

“By the way, you have a fan base who wants to see you on the field, wants you to be the savior, you’re the missing piece between a 3-14 team and a Super Bowl title,” Schofield said. “That’s a lot. Think back to when you were 21 or 22. You didn’t have fans over your shoulder with every move and you weren’t a finished product.”

Who prepares them for the pressure? Nobody. College coaches do not focus on NFL development and players come into the league after an exhausting pre-draft process. NFL owners want their shiny new toy quarterbacks to play right away and coaches believe they can coach up weaknesses. Oh, and then there’s coaches who aren’t willing to adjust their schemes to the player they drafted.

How does the NFL deal with it? Well, everyone has different methods.

Former NFL scout Brock Sunderland, who worked for the New York Jets from 2007-2012 and acted as a CFL general manager in Edmonton for five years, took note over years of evaluating players that a quarterback’s ability to navigate difficult situations most often equated to success or failure in the NFL.

“Every elite successful championship caliber quarterback I’ve ever been around in the CFL or NFL is that they are mentally tough and resilient,” Sunderland said. “If you don’t have that, close the door and move on. I’m not saying I have the answers but if you don’t have that everything else doesn’t matter. If you have that you have something to build around.”

The problem is that college quarterbacks do not always face adversity that is going to replicate anything like the week-to-week grind and pressure of the NFL, not to mention the adult stuff that comes their way quickly when they arrive in the pros.

“You walk in and you have probably had success at every level — high school, college etc. — and you have never really faced what you are going through at that time and you’re going through it on the most public stage possible and then you add in social media and those things, it wears on a person,” Sunderland said. “A lot of these players are under 25 years old, it’s a lot to shoulder and carry around with you on top of finances, moving to a new place, there’s so many things that go into it beyond X’s and O’s.”

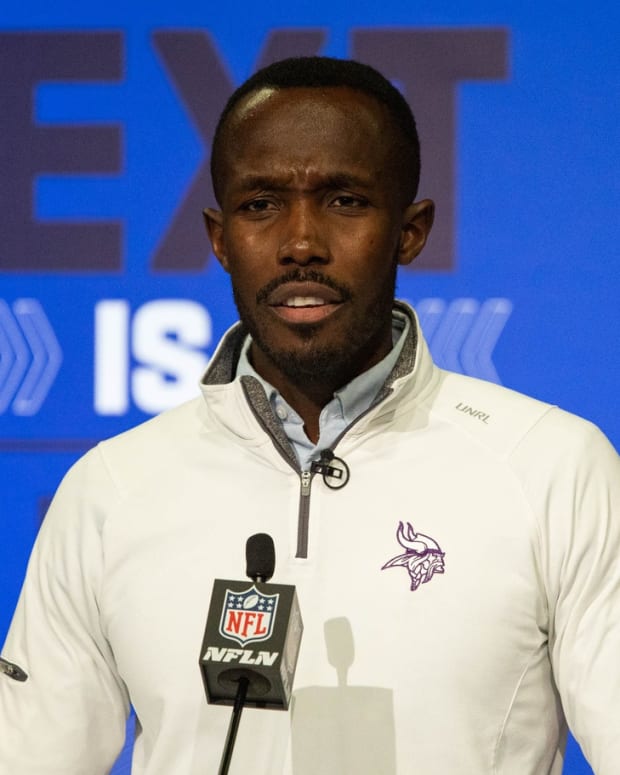

Brock Sunderland (right), a former scout and CFL GM, looks for how quarterbacks deal with adversity when scouting.

Photo courtesy CFL.ca

Sunderland considers lots of other factors. How many starts did the guy have in college? What type of system did he come from? But that method is tough to navigate because of how different college systems can be. The former scout recalled one year in which a quarterback that the team met with was spewing schematics like he had been in the NFL for years and another QB who told the team that his play call was dubbed “Number One” and he got the call from a big card on the sideline.

“Where you come from is a part of it,” he said. “Are you coming from a pro-style offense that parallels NFL ones or maybe not. Every franchise has that information and knowledge but there’s only so much you can guess. You never know how somebody is going to respond to all the moving parts and factors until they are in that situation.”

Sunderland pointed out that a scout can do everything right with his evaluation and a quarterback simply lands in the wrong situation.

“It’s not like basketball where one player can carry a team — they can improve it a lot and guys have done that but you need a supporting cast, offensive line, playmakers, there’s so much that goes into the recipe for the final product to be successful,” Sunderland said. “If you are throwing a young guy in there that doesn’t have all that it’s incredibly challenging. There have been quarterbacks who were talented enough to warrant where they were selected but they walk into a situation where the team isn’t talented enough.”

Former Buffalo Bills director of player personnel Jim Monos obsesses over the quarterbacks he got right and wrong. He loved Carson Wentz. Was that a hit or miss, he wonders. He was a big Mahomes guy and is proud of that one. He was also big on Byron Leftwich. He could talk about them for days. What he often comes back to is the glimpses that college quarterbacks give scouts of actual NFL plays. Oftentimes receivers are wide open and the pass rush is rarely bearing down in the same way we see every Sunday. Monos, a fan of statistical analysis, looks for truth within the numbers.

“I operate by a phrase called ‘Study The Stats.’ I think what happens — I love analytics and I love stats — when you see 65% completion percentage that doesn’t mean anything until you study the throws,” Monos said. “Is he making NFL throws and is he completing them? That’s how I study quarterbacks. What I call ‘Grown Man Throws.’ Who’s making the Grown Man Throws? When you watched Mahomes it was all grown man stuff, it was mind blowing.”

What he learned over the years was to lean into the quarterback’s strengths. If he did something outstanding in college, there’s a chance he can do it in the NFL, even if the competition is wildly more difficult and the schemes more complex.

“What was hard [about Mahomes] was that we had never seen it and you’re thinking, ‘is this just bad Big 12 defense? He’s not going to get away with this. You can’t throw across your body,’” Monos said. “You can because he did it on tape in college. Instead of ignoring it, appreciate it.”

Jim Monos, former director of player personnel for the Buffalo Bills.

Photo courtesy BuffaloBills.com

But Monos wonders if Mahomes would have his rings if he didn’t land in the right spot. That’s not to say he wouldn’t have been good — this good though? That, the ex-personnel man attributes to the connectedness of the Chiefs organization surrounding Mahomes.

“The core four is owner that spends money and stays out of the way, head coach and GM synced up and quarterback,” he said. “If you have the core four you have a shot, without it I don’t see how you do it.”

In the search for truth about quarterbacks we would be remiss if we didn’t include a quarterback.

When the Minnesota Vikings drafted Brad Johnson in the ninth round, they were taking a swing at a guy with only a handful of college starts for Florida State. They never would have guessed that he would eventually go 28-18 as a starter in purple and win a Super Bowl as Tampa Bay’s starting quarterback.

Brad Johnson spent years developing before getting his chance and then thrived with the Vikings.

Photo courtesy USA Today

How did the NFL miss on Johnson? There were 13 quarterbacks taken ahead of him and none of them put together the career that Big Brad did. Part of it, he says, was that he was a “late bloomer” but he mostly credits the opportunity he was given with the Vikings to develop. He was picked in 1992 and didn’t start a game until 1996.

“My first three years in the league I didn’t play with Rich Gannon and Jim McMahon as the starters,” Johnson said over the phone. “I was getting the time to develop. If I would have played my first or second year in the league I would have been retired after my first or second year. I wasn’t ready.”

Johnson believes that the NFL would have a higher hit rate on quarterbacks if they were willing to take a lesson from his story: Development matters. He points out that many of the great quarterbacks of his era got time on the bench before starting. He rattles them off like he’s thought about this subject before, name dropping Steve McNair, Brett Favre, Kurt Warner, Drew Brees, Carson Palmer, Michael Vick and Tom Brady as QBs who weren’t thrown right into the fire.

“My dad always said ‘it’s better to be prepared and not have an opportunity than to have an opportunity and not be prepared,’” Johnson said. “I was in one system for seven years under Brian Billick and I knew it. When I got my opportunity I was ready and with a good play caller and good players.”

Fit matters too. If a quarterback lands with a coach and system that doesn’t play to his strengths, there is a good chance the situation is going sideways.

“A guy like Anthony Richardson might not have fit in San Francisco but they had the same play caller that was in Philadelphia with Jalen Hurts and it was a good fit and has a good mesh with his style of play,” Johnson said. “Every play caller is different. Not everybody could play for Jon Gruden. He had a type of quarterback. Certain guys were great fits for him.”

That isn’t to suggest that all quarterbacks have the goods if they just get a chance to chill on the pine. If you were applying to play quarterback for Johnson, he’d ask you a pretty simple question: Are you tough enough for this?

“What is his grit? What makes him tick? What ring of fire have you been through in your life or career?” Johnson said. “Quarterback in the NFL, you’re going to throw interceptions and you’re going to lose games and you’re going to play injured and you’re going to have times where you stink and you’re the worst quarterback we’ve ever seen. What’s your ring of fire, man? Who is the kid? What is his toughness? What is he made of? That’s what a lot of it comes down to.”

Johnson acknowledges that kids these days do have it better than in his day when it comes to preparing for the NFL. In general, there are a lot more tools at the fingertips of players and the NFL when it comes to developing and identifying talent. Analytics are at the top of the list for new age helping hands, yet we have not yet see the league become better at QB evaluating in recent years.

When the New York Jets drafted Zach Wilson their post-draft team-released video showed the brass talking about his Completion Percentage Over Expected, a stat that is meant to evaluate the difficulty level of a quarterback’s throws. The Senior Bowl this year used tracking data to determine exact speeds of players, making the 40-yard dash antiquated. Teams were deploying the S2 test that claimed to “scientifically measures an athlete's game-speed cognitive abilities” but after CJ Stroud’s score (real or not) was leaked and he blew the league out of the water agents are refusing to have their players tested this year.

So what’s the best analytical approach? Are there numbers that actually correlate to success?

For that, we look to Kevin Cole, a data scientist who worked for Pro Football Focus and now authors the Unexpected Points newsletter. Cole ran a bunch of numbers looking for correlations between college underlying statistics and NFL performance and noticed that college QBs’ play under pressure had some connection to pro success.

That’s all well and good, unless the college quarterback was never under duress.

“Zach Wilson, the real problem was that he was never under pressure,” Cole said. “That’s somewhat the CJ Stroud thing. If you aren’t under pressure that much, we don’t know if you can deal with it.”

Another problem is that the pressure stats can change from year to year. If a quarterback has a great offensive line and receivers and then loses them to the draft then his numbers will decline even if he didn’t fundamentally change. Cole brings up the example that Will Levis might have been a top-five pick had he come out after his strong 2021 season.

There’s also the example of Josh Allen, who had nothing analytically to suggest that he was going to be good in the NFL except for his size and speed.

With more and more data available and teams adding data scientists to their front offices by the minute, it’s plausible in the future that the code will be cracked and there will be better identifying features for quarterbacks. But at the moment it’s difficult to have confidence in any combination of stats predicting outcomes. Even as one of the top in his craft at studying such matters, Cole still can only be sure that you have to play the lottery to win.

“The idea that I’d be confident in is that you should take quarterbacks, you should take them earlier, you should not worry about moving on from them earlier if they are not performing, you should not worry about ‘reaching’ or using a middle-to-late first-round pick on someone when there are busts with low value positions all the time. That’s my overarching philosophy now,” Cole said.

That makes the most sense philosophically but realistically you can’t ask coaches, general managers and owners to stake their careers on just taking a dude because — as the old New York Lottery phrase went — ya never know.

So the chase continues. This year there are five quarterbacks projected to be taken in the first round and the order in which they will be selected is mostly a complete mystery.

What have our analysts learned from their past failures that they will be applying this time around?

For Schofield, he’s always tweaking how much he should weigh certain characteristics in quarterbacks.

“There’s a basic template for quarterback evaluation but I liken it to when I was a lawyer and you argue that an expert opinion should get more weight because X or this fact in the case is critical because Y,” Schofield said. “What I’ve refined over the years is what traits deserve more weight generally and which ones deserve more for a quarterback today. Athleticism and the ability to create outside the pocket, when I started out [was less important].”

“You don’t want to wildly overreact to misses but you do want to take a step back and ask, where did I get this player right, where did I get this player wrong?”

Sunderland offers a reminder when it comes to the challenges of evaluation that often gets lost in the rat race for teams to pick apart every element of a player and for the outside world to turn up the heat on its hot takes in order to stand out in a crowded industry.

“It’s not an exact science,” Sunderland said. “You’re talking about people.”