Bud Selig turns short-term job into Hall of Fame plaque

OXON HILL, Md. (AP) On the day he was put in charge of baseball in 1992, Bud Selig said his new job was ''hopefully relatively short term.''

''But if you're asking me what relatively short term means, obviously this morning I don't know,'' he said.

Maintaining power for more than 22 years, Selig oversaw a revolution in baseball that included interleague play, the expansion of the playoffs from four teams to eight and then 10, dividing each league into three divisions with wild cards, instituting video review to aid umpires, revenue sharing to help small-market teams and 20 new big league ballparks.

He also presided over the first cancellation of the World Series in 90 years, an attempt to use replacement players for striking big leaguers and the unchecked rise and later crackdown on illegal steroids. He was head of baseball's labor policy when owners were found to have conspired against free agents.

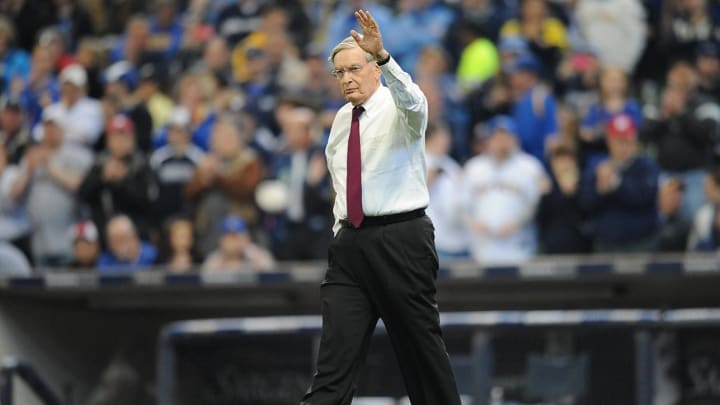

Selig's imprint was recognized Sunday when the 82-year-old was elected to the Hall of Fame by the Today's Game Era Committee.

''We were a sport resistant to change,'' he said. ''I believe in those years as commissioner, that's the most change in baseball history.''

Selig became the fifth of the 10 commissioners voted to the Hall, joining Kenesaw Mountain Landis (1920-44), Happy Chandler (1945-51), Ford Frick (1951-65) and Bowie Kuhn (1969-84). Every commissioner who has served at least five years is in Cooperstown.

''I'm happy for him. I think it's deserved,'' said Fay Vincent, the commissioner Selig helped force out. ''I think that after '94, Bud really got the point very clearly. I think Bud realized in '94 there was no point in trying to test the union anymore.''

Selig headed the group that purchased the Seattle Pilots in bankruptcy court in 1970 and moved the team to Milwaukee. A protege of Detroit owner John Fetzer, he became chairman of the owners' Player Relations Committee in early 1980s and directed strategy at a time owners were found to have colluded against players during three offseasons, leading teams to pay players a $280 million settlement.

Assisted by Chicago White Sox owner Jerry Reinsdorf, Selig was appointed to the newly created position of chairman of baseball's executive council two days after Vincent's resignation.

''Even I didn't understand the dimension of the problems we that we faced at that time,'' Selig said.

He repeatedly said he never would become commissioner, but he blocked Texas Rangers owner George W. Bush from taking the job, leading Bush to run for governor of Texas and later president.

After presiding over the strike and labor talks that led to an agreement in 1997, Selig finally was elected commissioner in July 1998 and accepted new contracts in 2001, 2004, 2008 and 2012. He announced in September 2013 that he would retire in January 2015.

Revenue rose from about $1.7 billion in 1992 to just under $9 billion in his final season.

''Bud will go down in history as the No. 1 commissioner that has served baseball, and without question,'' Peter Ueberroth, baseball's commissioner in the late 1980s, said as Selig's retirement approached.

Selig repeatedly said baseball had been stuck with economic rules designed when it was small business in the early-to-mid 20th century.

''We were living in a system that was archaic, hadn't been changed since what I call the Ebbets Field-Polo Grounds days,'' he said. ''There are a lot of small-market clubs that would tell you today they wouldn't be in business.''

While attendance boomed until the Great Recession and many teams helped start regional television networks, national TV ratings declined for baseball along with most other programming. Losing the 1994 World Series to a 7 1/2-month players' strike and widespread use of performance-enhancing drugs before the start of testing with penalties in 2004 were low-points in his tenure.

''Yes, it was terribly painful, broke my heart,'' he said of losing the Series. ''But it served I think as a great lesson, and we took it.''

Baseball's labor deal announced Wednesday runs through 2021, ensuring 26 years of labor peace since the last strike.

Steroids use increased through the 1990s, culminating in offense records that broke the season home run mark of Roger Maris and the career standard of Hank Aaron. Many of the hitters later were found to have used performance-enhancing drugs to build muscle.

''Steroids were not a baseball problem. Steroids are a societal problem,'' Selig said. ''For from a sport that never had a testing program, we came a long ways.''