The Cal 100: No. 6 -- Andy Smith

We count down the top 100 individuals associated with Cal athletics, based on their impact in sports or in the world at large – a wide-open category. See if you agree.

No. 6: Andy Smith

Cal Sports Connection: Smith coached the Bears' football team for 10 seasons, posting 74 victories, a program record that endured for 86 seasons.

Claim to Fame: Smith assembled Cal's Wonder Teams, which compiled a record of 44-0-4 from 1920 through 1924 and stunned the football world by routing Ohio State 28-0 in the Rose Bowl.

.

In 1916, a year after switching back from rugby to football, Cal hired 32-year-old Andrew Lathan Smith as its coach. It was a tumultuous time, with World War I on its way to claiming 16 million and the Spanish flu about to take 50 million more beginning in 1918.

Against this backdrop, Andy Smith sculpted a program whose success was unmatched across the country and still reigns as the most dominant era in Cal football history.

He developed the Wonder Teams, which from 1920 through ’24 were undefeated, compiling a record of 44 wins, 0 losses and 4 ties. When the Bears opened the ’25 season with a pair of victories, the unbeaten streak reached 50 games.

In 1960, the Helms Foundation selected the greatest American teams across a range of sports. Babe Ruth’s 1927 Yankees were chosen for baseball. Bill Russell’s 1959 Celtics were the pick for pro basketball.

Smith’s 1920 Golden Bears were judged the greatest college football team of all-time. Their resume was compelling: A 9-0 record, a 510-14 scoring avalanche against their opponents (including a 127-0 thrashing of Saint Mary’s), and a stunning 28-0 rout of heavily favored Ohio State in the Rose Bowl.

Cal’s dominance continued with records of 9-0-1 in 1921, 9-0 in ’22, 9-0-1 in ’23 (in brand new Memorial Stadium) and 8-0-2 in ’24. National championships were not crowned in that era, but the Bears’ 1920 and ’22 squads have since retroactively been given that honor.

By the time Smith’s 10-year run ended with his unexpected death on Jan. 8, 1926, he had compiled a record of 74–16–7. His victory total stood as Cal’s record for 86 years, until Jeff Tedford eclipsed it in 2011.

The architect of this unparalleled run, Smith lands at No. 6 in The Cal 100.

Born in 1883 in Pennsylvania, Smith played two seasons at Penn State before transferring to Penn, where the 6-foot, 200-pound fullback earned the nickname “the human battering ram” and was named to Walter Camp’s All-America teams as a senior in 1904.

Smith planned a career in real estate but joined the Penn staff as the freshman coach in 1905 and ’06 then became varsity backfield coach the next two seasons. Promoted to head coach in 1909, he was 30-10-4 in four seasons. Smith was hired by Purdue in 1913 and posted a record of 12-6-3 in three seasons before being recruited to Cal by Jimmie Schaeffer, who had been the Bears’ rugby coach and served as football coach in 1915.

Smith was hired with a salary of $4,500 and immediately knew what he had gotten into after meeting his neophyte players. “As far as knowledge of the game was concerned,” he was quoted saying in Ron Fimrite’s book, Golden Bears, “I might as well have gone to Russia.”

So the transition from rugby to football was difficult and the start of the war didn’t help, with players drafted into the military and travel schedules impacted. Still, Smith’s early teams were 24-13-5 over four seasons.

In 1918, Smith made the shrewd decision to hire Clarence “Nibs” Price as an assistant coach. Price eventually succeeded Smith as the Bears’ head coach and also was Cal’s basketball coach for 30 seasons through the early 1950s.

But Price’s immediate contribution was on the recruiting front, where he helped bring an assortment of talented players, including Pesky Sprott, Cort Majors, Stan Barnes, Charlie Erb and Harold “Brick” Muller. The 1919 freshman team went 11-1 and fueled the five-year run of the Wonder Team.

Price also served as an important conduit between Smith and his players, who had threatened to leave in 1919 if the coach didn’t scrap his brutal practice of “Elimination Day,” a grueling practice designed to weed out all but the toughest players. Smith agreed and the stage was set for a remarkable run of success.

The Bears did not lose another game until 1925.

Smith’s teams played a brand of football that would seem foreign to modern fans. He emphasized aggressiveness, obedience, concentration and determination meshed with harmonious co-operation.

But he played a conservative style summarized by the motto "Kick and wait for the breaks.” Smith punted early and often — sometimes even on first or second down — determined to push the opponent deep on its own territory and rely on defense to create scoring chances.

He also sprinkled in trick plays, such as the one where Muller, an end, threw his famous long touchdown pass in the Ohio State victory.

After its stunning win over the Buckeyes, the Bears played in the Rose Bowl again a year later, against Washington and Jefferson. Smith had reservations about the game, convinced the Presidents, as they were known, stocked their roster with “ringers.”

Cal was heavily favored to win at Pasadena but the game, played on a soggy field following a rainstorm the night before, would up a scoreless tie. Smith declined subsequent two invites to play in the Rose Bowl.

That conviction would seem to go hand-in-hand with a comment Smith made in what is thought to be his final newspaper interview in Philadelphia shortly before his death:

"Winning is not everything and it is far better to play the game squarely and lose than to win at the sacrifice of an ideal.”

Smith, who was known to be a heavy drinker away from the field, came down with pneumonia late in the 1925 season. Cal team physician Dr. Frank Smith encouraged him to get rest, but Smith reportedly said, “I can’t quit now with the Big Game only a week away.”

Cal lost to Stanford 27-14 that day and Smith decided to travel to Philadelphia to attend the Penn-Cornell game. He also attended the Army-Navy game in New York City.

He became ill again on Dec, 20 while in his Philadelphia hotel room and was hospitalized when the pneumonia worsened. He died Jan. 8, 1926, reportedly having just agreed to a five-year contract extension.

The college football world was shocked by the death of the 42-year-old. The Register-Guard newspaper in Eugene, Ore., ran a headline announcing his death at the top of its front page. Cal canceled its home basketball game that night.

“It is loss we can never fill,” former Cal player Tut Imlay said.

His ashes were dropped by an airplane over the stadium and thousands attended his service at Memorial Stadium.

University president Dr. William W. Campbell praised Smith in his remarks to the crowd: “He realized the proper place of football in the university and cooperated with the administration of the university at all times. . . . Andrew Smith stood the test of victory and defeat.”

Unmarried and without family, Smith left all of his $30,000 estate to the university: $10,000 for the establishment of two football scholarships for upperclassmen, $2,000 for the Berkeley Elks lodge, and $18,000 to be divided between the California Beta of Sigma Alpha Epsilon and Skull and Key society.

Two years after his death, a committee of former Cal players, headed by 1920 team captain Cort Majors, commissioned the Andy Smith Bench, a 42-foot long structure made of gray granite and teakwood and weighing more than 17,000 pounds. It was inscribed with a dedication and two quotes from Smith, including one that read: "We do not want men who will lie down bravely to die, but men who will fight valiantly to live.”

The Andy Smith Bench remained on the home side of the field for 83 years until Memorial Stadium underwent renovations following the 2010 season. It now resides in a public area atop the stairs leading to the north entrance to the facility.

Smith was inducted into the National Football Foundation Hall of Fame in 1951, along with his first star player, Brick Muller. Smith was chosen to the Cal Athletic Hall of Fame in 1986.

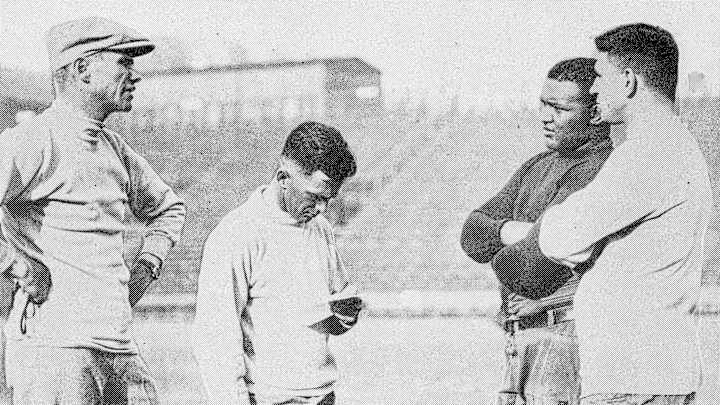

Cover photo of Andy Smith, far left with his coaching staff, courtesy of Cal Athletics

Follow Jeff Faraudo of Cal Sports Report on Twitter: @jefffaraudo

Jeff Faraudo was a sports writer for Bay Area daily newspapers since he was 17 years old, and was the Oakland Tribune's Cal beat writer for 24 years. He covered eight Final Fours, four NBA Finals and four Summer Olympics.