Dr. Z’s Ultimate Legacy

This week at The MMQB is dedicated to the life and career of Paul Zimmerman, who earned the nickname Dr. Z for his groundbreaking analytical approach to the coverage of pro football. For more from Dr. Z Week, click here.

When I was growing up, Sports Illustrated had three NFL kings: Michael Silver, master of profiles; Peter King, master of information; and Paul Zimmerman, aka Dr. Z, master of analysis. Before I ever had a real job, I would spend summers writing my own NFL preview book, trying to make my style a blend of all three—a lofty but unattainable goal.

Around Labor Day each year, my book would be finished and I’d send it to various respected sportswriters in search of feedback. My one and only interaction with Dr. Z came in mid-September 2008, my sophomore year of college. He sent an email saying only this: The time to send me your preview book was BEFORE the season. It is of no good to me now.

In reply, I agreed wholeheartedly but tried to explain that early September was the best I could do as a one-man operation. Then I mentioned how much I loved his weekly picks column in the magazine. He quickly wrote back: Apparently you don’t read SI.com. The website is where we writers actually have freedom anymore. It’s where we all do our best work. In the magazine I write a half-assed, heavily edited column. It’s nothing I’m proud of.

Over the years, I’ve heard about Dr. Z’s bluntness and his bristly, old-school personality. Both fortunately and unfortunately, I’ve never encountered this in the flesh. But those who were around Dr. Z must have, deep down, appreciated his demeanor because they speak of him with great reverence. They say there was an honest simplicity behind his directness, which didn’t necessarily mitigate the sting of his critiques but somehow made it all okay. You weren’t the only one being singled out by a grizzled veteran; he was merely the professorial type who didn’t suffer fools. That consistent honesty and directness defined Dr. Z’s writing and football analysis.

As the years went by, my own NFL focus drifted more and more in the direction of Dr. Z’s. The NFL is packed with interesting people and circumstances, and it’s great having the Michael Silvers and Peter Kings of the world tell those stories. But for me, the football itself is the most interesting part.

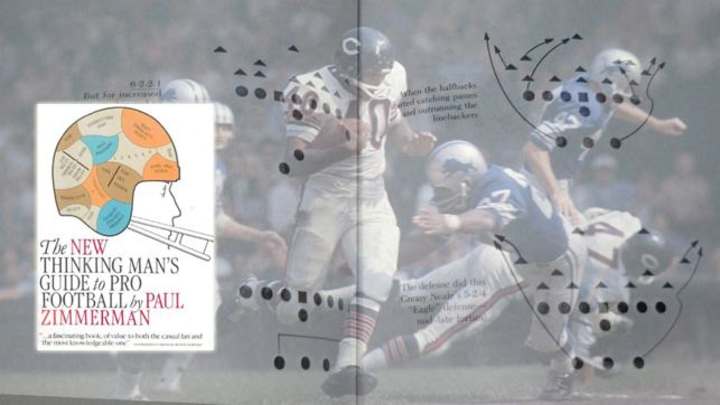

Every once in a while, when someone is feeling especially generous, they’ll pay me the compliment by comparing me to a young Dr. Z. And because of that, my boss, Peter King, asked me to write this essay. He also gave me my first reading assignment since college: Dr. Z’s The New Thinking Man’s Guide to Pro Football. The book, published in 1984, contains some of his most defining work, but I’d never read it before. To be honest, football from before my lifetime has never really interested me. The game was just so different then.

Peter gave me his copy of the book and said I could mark it up. I intended to highlight all of Dr. Z’s prescient, time-tested thoughts in pink and all of his off-target ones in blue. But after about 30 page turns and many, many lines of pink text, I drifted into just highlighting points that I could steal or expound upon today. The blue pen morphed into a tool for writing longer extolments of those points in the margins.

A few of my favorites:

In describing the schematic wrinkles Vince Lombardi used as offensive coordinator to improve the New York Giants’ running game, Dr. Z. wrote: He employed the exceptional talents of Roosevelt Brown as a pulling tackle. And he took the heat off the center by moving the guards out wider, creating splits in the middle of the line and rendering obsolete the huge defensive middle guards.

An offensive line’s splits—the actual distance between each lineman—are something that few people notice but coaches constantly think about. Dr. Z identified it as a key trait to arguably the most famous play in pro football history: Lombardi’s sweep.

I also admired Dr. Z’s analysis on running backs. It was simple but brilliant: Running back is a position governed by instinct and … the great ones usually run with their feet close the ground—Sayers, Brown, Jimmy Taylor, Perry, they all did it. He goes on to assert that for running backs, speed is overrated (I agree). Then he makes a point I’d never considered: The actual mechanism of carrying the football slows people down … Pure track athletes who pop up in the pro football drafts come in as wide receivers, occasionally as defensive backs, but seldom as running backs. Their speed is used for running without the ball.

Dr. Z’s explanation here reminds me of something I once heard about Bill Walsh. Apparently Walsh had an unbelievable ability to state something with such pure simplicity that whatever he said would immediately seem obvious, leaving listeners to wonder how they’d never thought about that themselves.

Several times in the book, Dr. Z talked about how the additional bars on face masks led to the head being used more as a weapon, both in blocking and tackling. This changed the equation of football, making the sport, as Dr. Z suggested before anyone heard the acronym C-T-E, significantly more dangerous.

As you might expect with an opinionated tome that exceeds 400 pages, there were times when I simply disagreed with Dr. Z. He was more interested in statistics than I think an astute observer of the game needs to be. The problem with statistics is they’re almost always viewed through the lens of known results. In other words, when you know a win/loss outcome, statistics can be twisted to say what you want them to say.

I thought Dr. Z did this when talking about Dan Fouts’ passing numbers. Explaining that Fouts had 25 games of 300-plus yards passing in the Air Coryell years with the Chargers, and that his record in those games was 14-11, Dr. Z argued that the stats didn’t tell the whole story. Because during that same five-year span, he wrote, the Chargers’ record in games in which Fouts did not throw for 300 yards was 32-12.

Often, more passing yardage comes in defeats because the yards get accumulated when the offense is playing from behind and the defense, protecting a lead, is playing softer. Rushing numbers tend to rack up in the inverse way: if the Chargers were ahead, they were liable to protect their lead and milk the clock by running more than throwing. That’s going to impact a quarterback’s passing yardage.

I pick this bone only because statistics have gained more and more credence over the years, and that’s not necessarily a good thing. (I often arm wrestle with my editors about highlighting statistics and even the scores of games in my Deep Dive columns.) Football isn’t purely fluid like basketball, and it’s not purely regimented like baseball. And so every stat must be contextualized in a granular sense.

There were also instances where Dr. Z made predictions that didn’t pan out. He didn’t talk about it in The New Thinking Man’s Guide, but he’s most notorious for outright dismissing Dan Marino when the Dolphins selected him in the 1983 draft. “I don’t understand it,” he said on ESPN’s broadcast, and questioned how Marino would develop under Don Shula’s staff.

To this I say: if a known blowhard is flubbing predictions, fire away with all the criticism you want. But with someone like Dr. Z, who was simultaneously a student and teacher of the game, if you aren’t whiffing every now and then, well, you’re not taking enough chances to venture outside the box. It’s better to come at something from an intellectual or entertaining angle and be wrong than it is to be blandly, safely, boringly correct by pointing out the obvious or nothing at all.

Dr. Z’s best attribute: the way he seamlessly intertwined his honest, direct writing with smart, entertaining anecdotes and accessible examples. He had a way of schooling readers by transitioning little picture items into the big picture, which helped broadened his appeal to a wider audience. Look at how he dissects safeties, the hardest position to see on TV and therefore the least understood:

Everyone’s concept of safeties is different. The positions became defined into strong and free, or weak, in the sixties, but some teams, such as Seattle and Minnesota, still kept the old designations of left and right through the eighties. Pittsburgh rotated three men at the two spots last year. Dallas has been situation-substituting strong safeties for a few years, using one stronger run-stopper on early downs and replacing him with a ballhawk in passing and nickel defense situations. Both Dallas safeties are usually so run-conscious that last year, in the Cowboys’ second game against the Redskins, the Skins started off with three wide receivers, to force one of the safeties out of the crunch in the middle and into man coverage, providing more room for John Riggins to run.

Dr. Z must have also been an incredible interviewer. Some of the quotes in his book are like nothing you’ll find anywhere else.

Of the great Paul Brown, Tom Landry told Dr. Z: “(He) was such a meticulous coach that if you gave him something he’d never seen before, he became flustered.” Imagine social media’s reaction today if a writer got a head coach—any head coach—to admit something like this about, say Bill Parcells.

It wasn’t always the controversial quotes Dr. Z got, either. He had a way of bringing out an interviewee’s creativity. Of former Houston quarterback Dan Pastorini, Dr. Z wrote: A bright young quarterback on the worst team in the NFL. He’d get sacked five or six times a game, get his nose broken, teeth knocked out and wrists and fingers mangled—and the crowd would boo him. On this, Pastorini told Dr. Z, “It’s like being in a street fight with six guys, and everybody’s rooting for the six.”

Of Lawrence Taylor, New York Giant Beasley Reece told Dr. Z, “Everyone knows he’s (blitzing). It’s like a cop putting sirens on his car.”

I would love to know what Dr. Z thinks about today’s NFL. In his book, he lamented how the NFL had altered its rules to make things easier on offenses, particularly the passing game. Presciently he wrote: If you don’t have a quarterback who’s capable of a 300-yard, four-touchdown game every now and then, you’re in trouble. He took repeated swipes at the league’s decision-makers, like the one on page 131: Football is a cyclical game and I think we’ll see the end of the offensive cycle and a return to defense, as we had in the seventies, unless the rulemakers start messing around again.

Show some of today’s game film to Dr. Z and duck.

Dr. Z saw the game from a player’s perspective because he learned its nuances in the trenches. He played offensive line at Stanford and Columbia, which explains why his football acumen and writing is sharpest on the topic of blocking. Dr. Z. also learned to explain the game from a writer’s perspective, because, well, he grew up as one of those, too. At Columbia he wrote for the Daily Spectator. After college, he briefly played minor league football, in 1963, before becoming a New York newspaperman from then until 1979, when he joined SI.

The New Thinking Man’s Guide to Pro Football is an enlightening read. The first half of the book has the best on-field information; the second half focuses on the sport’s peripheries—things like training camp, the art of scouting, and life in the press box. Timeless writing and his prescient analysis might be Dr. Z’s ultimate legacy. As he told me in that email exchange, online is where he published his best work late in his career. How many other bristly newspapermen of the 1960s could say that?

• Question? Comment? Let us know at talkback@themmqb.com