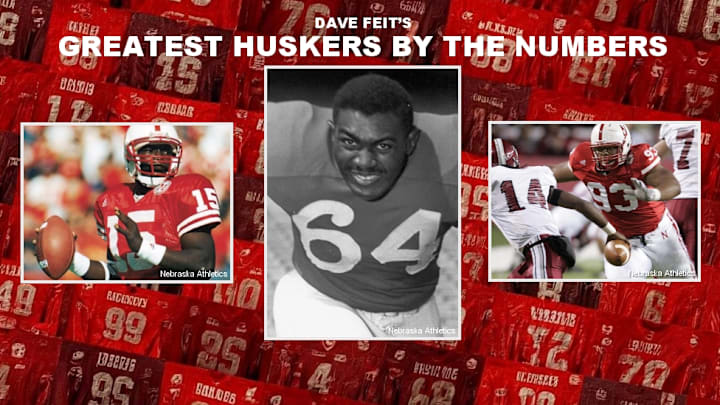

Dave Feit's Greatest Huskers by the Numbers: 64 – Bob Brown

In this story:

Dave Feit is counting down the days until the start of the 2025 season by naming the best Husker to wear each uniform number, as well as one of his personal favorites at that number. For more information about the series, click here. To see more entries, click here.

Greatest Husker to wear No. 64: Bob Brown, Guard / Linebacker, 1961 – 1963

Honorable Mention: Charles Bryant, Jim McCord

Also worn by: Stan Hegener, Brad Johnson, Kurt Mann, John Roschal, Mike Tramner, Jon Zatechka, Chris Zyzda

Dave’s Fave: Charles Bryant, Guard, 1952 – 1954

Bob Brown came to Nebraska in 1961, one year before Bob Devaney. Brown played sparingly in this first season under coach Bill Jennings. When Devaney arrived from the University of Wyoming, he was astonished by Brown’s size (6’5″, 260 pounds) and strength. With his physical gifts, why wasn’t Brown playing?

Devaney soon realized the reason. The basic bumps and bruises of the game were often treated as serious injuries. Brown would miss practices and was gaining a reputation on the team as a goldbricker.

Coach Devaney brought Brown into his office and suggested he quit football. “We recommend golf, or maybe tennis, where you can use your strength without getting hurt,” Devaney quipped.

The message was received. Brown pleaded to remain on the team and worked his way into the starting lineup of Devaney’s first team in 1962. By the end of the season, Brown was voted All-Big Eight as a guard.

The 1962 team got off to a great start, winning its first six games. The second game – a 25-13 win at Michigan – is still viewed as a monumental moment in program history. Bill “Thunder” Thornton scored two touchdowns. On the final run, he said “(Brown) knocked out the whole side of the Michigan line. Why, he must have knocked down six men.”

The 1962 Wolverines were not a great team (they finished 2-7), but knocking off a vaunted brand on the road was a confidence boost and a message to the rest of the country. Nebraska was becoming a force to be reckoned with.

Devaney once said “Boomer” Brown was the best two-way player he ever coached. A fearsome linebacker, Brown had 49 career tackles. His interception in final minute of the 1962 Gotham Bowl sealed Nebraska’s 36-34 win over Miami – NU’s first-ever bowl game victory. Bob Devaney’s tenure at Nebraska was off to a great start.

In 1963, Brown anchored the offensive line for a Cornhusker team that won the conference for the first time since 1940. Brown repeated as an all-conference selection and was a unanimous All-American – Nebraska’s first All-American player since Jerry Minnick in 1952. More importantly, Bob Brown was the first black player at Nebraska to earn All-America honors.

Brown was the first overall pick in the AFL draft (Denver) and the second overall pick in the NFL draft (Philadelphia). After a lengthy NFL career with the Eagles, Rams and Raiders, he was elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2004.

Brown is one of just three Cornhuskers to be enshrined in the College and Pro Football Halls of Fame. And yet, Brown said there was only one Hall of Fame he wanted to be in. “I didn’t need to be applauded. I needed for you, as a defensive end, to put me in YOUR Hall of Fame… I needed for you to walk off the field and look back over at me and think ‘Boy, I don’t want to see him again!'”

Bob Brown is one of the greatest players in Nebraska football history. Those who saw him play swear he is the greatest offensive lineman to ever play at Nebraska.

In 2004, the number 64 was permanently retired at Nebraska in honor of Robert “Boomer” Brown. He is one of just three Cornhuskers to have his number no longer issued.

***

As you may know, Nebraska’s first black player was George Flippin, who played from 1891 – 1895.

Despite being an excellent halfback, Flippin’s presence on the team was controversial. Missouri chose to forfeit its 1892 game against Nebraska instead of being on the same field with a black player. Flippin – who went on to become a doctor, opening a hospital in Stromsburg, Nebraska – was a true pioneer and hero. Flippin played thirty-some years before uniform numbers were utilized, otherwise he would definitely be in this countdown.

After Flippin, Nebraska had a handful of black players on its rosters. But the racist realities of the era – both in Lincoln and in some of the places Nebraska regularly played (namely, Missouri and Oklahoma) – meant the Huskers stopped having black student athletes on their teams. Clinton Ross, a guard on the 1913 team, was the last black player to letter at Nebraska for almost 40 years.

In 1946, the legendary Lincoln Star sports columnist Cy Sherman wrote “I have been advised, but never officially, that a gentleman’s agreement has been in existence for some years within the (Big Six) conference, according to the terms of which negro players are deemed undesirable in football and other contact sports.” Sherman stated it was “common knowledge” that the gentleman’s agreement originated at Oklahoma and Missouri.

In the late 1940s, the tide slowly started to shift. Student governments at Kansas and Nebraska spoke out against the gentleman’s agreement. In 1947, Nebraska’s Student Council asked NU to withdraw from the Big Six Conference if the ban on black athletes was not lifted. But as Sherman wrote: “Prejudices are deep seated and often unreasoning in those states, and any endeavor to convince the average Missourian or Oklahoman that a negro has his rightful place in the Big Six football doubtless would be doomed to fail.”

Kansas State encouraged a local black player, Manhattan High’s Harold Robinson, to join the team in 1948, and placed him on scholarship for the 1949 season. He was allowed to play at OU and Mizzou, but he was segregated from his teammates while in those states. He endured racial slurs and physical play in games, but he broke the conference’s “color line.”

Charles Bryant broke the color line at Nebraska in 1952.* A multi-sport star at Omaha South, Bryant watched as two of his white teammates were recruited to NU by coach Bill Glassford. Bryant’s high school coach told him “You’re going to go play football at Nebraska. Get in that truck.”

*It is worth noting that Tom Carodine, a black halfback from Boys Town did play for Nebraska in 1951. He rushed for 101 yards against TCU in the opener and scored a touchdown in the 1951 Kansas State game, a 6-6 tie that later became a 1-0 forfeit because the Wildcats used ineligible players. However, Carodine was kicked off the team less than two weeks later for cutting classes and missing a practice. Carodine does not appear on any rosters from the 1951 team and did not receive a varsity letter. Bryant – who did letter – is thus credited with breaking the color line.

At NU, many of Bryant’s teammates – especially those from smaller Nebraska towns – had never met a black man before. Bryant was either ignored or treated like, as he put it, “a spaceman.” But his athletic successes – he was an All-Big Seven guard in 1954 and earned three letters in wrestling, including the Big Seven championship in 1955 – earned him respect on campus.

But it did not help south of Lincoln.

On some road trips, he would have to sleep at the black YMCA or on the team bus. If a restaurant refused to serve him or his black teammates (Sylvester Harris and Jon McWilliams joined NU in 1953), they would have to rely on their white teammates for dinner.

A 2014 profile on Bryant (and his grandson Brandin Bryant, whose Florida Atlantic team was preparing to play Nebraska) put some perspective on the discrimination and segregation Bryant faced.

The Omaha World-Herald’s Dirk Chatelain wrote that “on the last road trip of his career, the 1955 Orange Bowl, he was barred from the hotel lobby and the swimming pool. On New Year’s Day afternoon, he led NU with 14 tackles.”

I find this quote – taken from a 2011 profile by Leo Adam Biga – very insightful on what made Bryant successful:

“I was tenacious. I was mean. Tough as nails. Pain was nothing. If you hit me I was going to hit you back. When you played across from me you had to play the whole game. It was like war to me every day I went out there. I was just a fierce competitor. I guess it came from the fact that I felt on a football field I was finally equal. You couldn’t hide from me out there.”

Charles Bryant was a true trailblazer who helped pave the way for thousands of black athletes at Nebraska, including Bob Brown.

More from Nebraska on SI

Stay up to date on all things Huskers by bookmarking Nebraska Cornhuskers On SI, subscribing to HuskerMax on YouTube, and visiting HuskerMax.com daily.

Dave Feit began writing for HuskerMax in 2011. Follow him on Twitter (@feitcanwrite) or Facebook (www.facebook.com/FeitCanWrite)