Book Excerpt: Issei Baseball: The Story of the First Japanese American Baseball Players

Continuing with our series of book excerpts, we are pleased to present a chapter from Issei Baseball: The Story of the First Japanese American Baseball Players, by Robert K. Fitts.

I asked the author to give us the elevator speech; a one-minute introduction to his work. Here is that explanation, followed by the text of Chapter 4:

Baseball has been called America’s true melting pot, a game that unites us as a people. Issei Baseball is the story of the pioneers of Japanese American baseball, Harry Saisho, Ken Kitsuse, Tom Uyeda, Tozan Masko, Kiichi Suzuki, and others—young men who came to the United States to start a new life but found bigotry and discrimination.

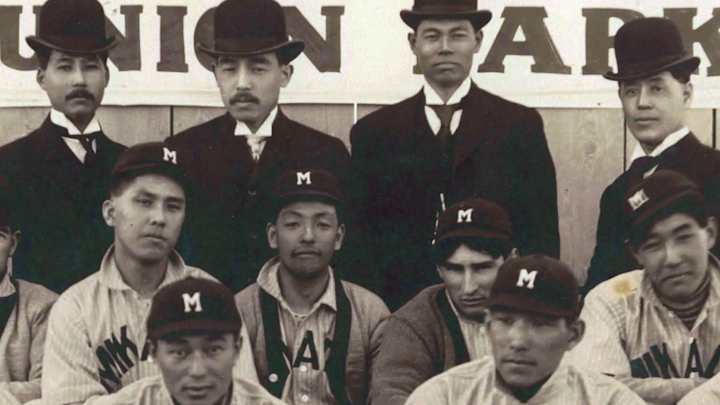

In 1905 they formed a baseball club in Los Angeles and began playing local amateur teams. Inspired by the Waseda University baseball team’s 1905 visit to the West Coast, they became the first Japanese professional baseball club on either side of the Pacific and barnstormed across the American Midwest in 1906 and 1911. Tens of thousands came to see “how the minions of the Mikado played the national pastime.” As they played, the Japanese earned the respect of their opponents and fans, breaking down racial stereotypes. Baseball became a bridge between the two cultures, bringing Japanese and Americans together through the shared love of the game.

Chapter 4, entitled Issei Baseball, introduces Tozan Masko, who would become the first Japanese manager/promoter of a professional ballclub, and discusses the beginnings of Japanese American baseball in Los Angeles and other cities.

Excerpt begins here:

Tozan Masko was a precocious young man. He was the third son of Kurobei Mashiko, a large landowner and entrepreneur from the village of Niida in the Iwase district of Fukushima Prefecture. Born on July 4, 1881, his parents named him Takanori. Japanese kanji can be pronounced in several ways, so the characters used to write his name can also be read as “Koji.” Throughout his life he would use both variations as his first name but usually went by his nickname, Tozan. He, or his father, also shortened the last name to Masuko. Later in life Tozan would Anglicize the last name to Masko.

Niida was a remote village with a population of just 2,375 in 1889. To pursue his business interests Kurobei maintained a home in Tokyo, where Tozan may have been born and raised. As a young teen in Tokyo, Masko frequented the offices of the Yamato newspaper, the third or fourth largest newspaper in the country with a circulation of 20,000– 28,000. It was known for its gossip columns and color wood- block prints (nishiki- e) of significant events. Young Tozan impressed the reporters with his intelligence and drew the attention of prominent politician and fellow Iwase native Hironaka Kono. A fierce supporter of the Meiji Restoration and democracy, Kono realized that Japan would soon become a world power and advised Masko to study in the United States to master English and receive a Western education.

On April 17, 1896, fourteen- year- old Tozan Masko boarded the ss Doric in Yokohama to begin his journey. He traveled without a chaperone or companion in Asiatic steerage. Fortunately, the voyage was uneventful and quick. Not making the usual stop in Honolulu, the Doric went straight from Yokohama to San Francisco, setting a record for the fastest Pacific crossing at twelve days, twenty- two hours, and eighteen minutes. After a brief stay at the Angel Island quarantine station, Masko entered San Francisco on May 1, 1896.

Masko settled at the Japanese Methodist Episcopal Mission at 1329 Pine Street, between Hyde and Larkin Streets, on the southwest slope of Nob Hill. Just a few blocks away, at the crest of the hill, stood the magnificent mansions of San Francisco’s elite. But at the hill’s base the neighborhood was decidedly more modest. Two- story wooden houses divided into “flats” lined the streets, alongside larger, three- story boarding houses and light industries—printing, carpentry, and machine shops. The area was gritty. Coal- burning furnaces in nearly every dwelling created perpetual smog, exacerbated by the city’s famous fog. With the smog came a fine black grime that settled on every surface. A coal yard located just three doors down made the Japanese mission especially dirty. In these pre-automobile days horse dung and garbage littered the street. Stables stood on nearly every block, further assaulting one’s sense of smell. To repair the horses’ shoes the local farrier’s hammer could be heard banging throughout the day. On top of this the sickly- sweet smell of yeast and hops from the large San Francisco Brewery and the Golden Gate Yeast Company, located just a block away at 1426 Pine, permeated the neighborhood.

One block north of the mission stood the remarkable Lurline Salt Water Baths, a large two- story building containing a 150-x-75- foot unheated salt-water swimming pool with two water slides. Water for the pool was drawn daily from San Francisco Bay, piped four miles to the company’s five- million- gallon reservoir and then on to the pool. Private steam-heated baths were available on a balcony above the pool. Both the pool and baths were open to the public for a cost of just thirty cents, including a rental bathing suit. Special hours, 9 a.m. to 12 p.m., twice a week, were set aside for women bathers.

Masko, along with about thirty other Japanese men, lived in a two-story wooden dormitory positioned immediately behind the church. The residents were fed three meals a day in return for a nominal fee and chores. No alcohol or gambling was permitted. A national report of the Methodist Episcopal Church noted that the mission’s “aim is to keep the church abreast of the needs of the people, and for this purpose there is maintained the Anglo-Japanese Training School, . . . an English language school . . . [that] seeks to fit pupils for the schools in America.” The course of study was challenging, taking three years to complete, and few residents finished the program. In 1900, the only year that still has surviving data, as many as two hundred men enrolled in the school, but only six graduated.

Young Masko excelled at the mission school. Industrious and ambitious, he picked up English quickly and helped organize a student club. When not attending classes, Masko worked at the Shin Sekai newspaper, a Japanese language daily founded in 1894 by Hachiro Soejima. Although Shin Sekai would become one of the leading Japanese papers in California, at the time it was still a small enterprise with a circulation of just two hundred.

In the summer of 1897 Masko was ready leave the mission and find a job. He took out an advertisement in the help wanted section of the June 26 issue of the San Francisco Chronicle: “Japanese boy wishes a situation to do light housework: has good recommendation. Please address G. Masuko 1329 Pine St.” Although Masko would use a Japanese surname for most of his life, he would occasionally, especially when interacting with Anglo-Americans, use “George” as his first name. The advertisement ran for only one week as Masko found employment as a chef in the household of Claus Spreckels, the largest beet sugar manufacturer in the United States, whose son owned the neighboring Lurline Salt Water Baths. Masko worked and lived at one of the Spreckels’s estates in the Santa Cruz area, where he also attended an American high school and became an avid baseball player.

After four years with the Spreckels, Masko returned to the Shin Sekai newspaper in 1902. Newspaper founder Hachiro Soejima placed him at the head of the paper’s Fresno office, where he remained for a year and a half until he was forced to resign. The reason for his resignation is lost to time. The record only states that the transgression was another’s fault. In 1904 Masko, now nearly twenty-four years old, moved to Los Angeles to take a job with the Rafu Shimpo newspaper.

At the beginning of the twentieth century Los Angeles contained a small but rapidly expanding Japanese community. In 1890 fewer than a hundred Japanese lived in the city, but fourteen years later the community had grown to nearly four thousand. By 1907 the population would rise to six thousand. Nearly all these new residents were men. Known as birds of passage— deseki in Japanese— they planned to stay in the United States a short time, earn as much as possible, and return to Japan with enough money to purchase a farm or business and start a family.

Japanese-owned boarding houses and supporting businesses sprung up to accommodate the new arrivals. Most were located around North San Pedro Street and First Avenue, an area that would become known as Little Tokyo. By 1907 there were more than sixty Japanese-owned lodging houses and a half dozen pool halls, as well as barbershops, groceries, and other businesses. There were also over sixty Japanese-owned restaurants, which catered to their own countrymen instead of serving the general American- born population. Many were drinking establishments known as nomiya. With the large, transient, mostly male population came problems. Public drunkenness and disorderly behavior became nightly occurrences, brawls increasingly commonplace, and gambling and prostitution widespread.

As Los Angeles’s Japanese community grew, two young students at the University of Southern California saw an opportunity. There were no local Japanese-language newspapers. To get their news Japanese speakers relied on papers printed in San Francisco. Seijiro Shibuya, a twenty-five-year-old son of a wealthy Tokyo samurai family, and twenty- six-year- old Masaharu Yamaguchi, a graduate of Tokyo Imperial University, created the Rafu Shimpo (Los Angeles Currier) in April 1903. The first issues came out sporadically, written by hand and mimeographed.

Within months the newspaper prospered, and Yamaguchi returned to Japan to purchase a set of printer’s type in Japanese— an item unavailable in the United States. The founders set up offices in four cramped rooms on the second floor of 128 N. Main St. (where City Hall now stands) and hired a small staff. On February 1, 1904, the paper began as a daily.

The paper soon attracted a number of bright, progressive, ambitious young men as writers and editors. Tozan Masko joined the staff in the spring, and a few months later, in August 1904, Hanzaburo Harase came on board as a writer and editor. A graduate of either the Japanese Naval School or the aristocratic Peers College (sources differ), Harase arrived in the United States to visit the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis and then settled in Los Angeles. A brilliant, creative thinker, he would eventually become a successful businessman, engineer, and inventor, holding several mechanical patents. Harase was said to have a “sense of humor so great that he could compete with Charlie Chaplin.”

The pay at Rafu Shimpo was poor. As chief editor, Shibiya made $25 per month; Harase and the other editors/writers received $15– $18. (At the time uneducated day laborers made one dollar per day.) On these meager salaries the writers could not afford to rent an apartment, so most slept and cooked their skimpy meals in the cramped newspaper offices. When the office was full of sleeping writers and printing supplies, reporters would sleep in the “black only” bathroom (restrooms were segregated at that time) located on the building’s second floor.

With the start of the Russo-Japanese War the paper’s circulation rose from 250 to 400 as Japanese immigrants wanted to stay abreast of the latest developments. Unable to keep up with the increased demand in the tiny second- floor rooms, the paper moved to the building’s larger basement in 1905. Despite its rising sales, the newspaper remained amateur. Articles and editorials were often poorly thought out, recklessly opinionated, and needlessly argumentative. Such flaws led to libel suits and disputes with prominent members of the Japanese community.

The writers were a young, rowdy bunch. Nearly all were sons of ex-samurai families, educated at the top schools in Japan before coming to California to further their education or make their fortune. Los Angeles offered many vices, and Rafu Shimpo’s staff sampled them regularly. In 1929 Harase remembered having to rouse hungover writers sleeping in the segregated bathroom. “Tozan Masko and Kotan Saito asked for a few minutes, put their heads into the dirty toilets, and flushed water over their heads. They then claimed that they felt better.” Saito’s and fellow editor Yoshio Sato’s drinking binges would occasionally shut down the newspaper. Without their contributions the paper could not go to press, and after particularly raucous evenings the next day’s issue would have to be canceled. The paper kept the type assembled to print a one- page apology “saying that there would be no issue as the printing press was broken” just for these occasions.

The drinking sometimes led to brawling. On Harase’s second day at the paper he arrived at the office and “was first surprised by the smell of alcohol, second by groans, and by finding a monster-like person, named Ono, sleeping on the floor wrapped in a newspaper. His face looked just like a bulldog’s. Shibuya was sleeping right next to him. He didn’t seem to have a nose either. They looked very different from how they had looked the day before. Apparently, Shibuya had gotten into a fight with a police officer the night before. Ono tried to stop them but also got hit. No wonder I couldn’t see their noses in their swollen purple faces.”

Some staff members frequented Los Angeles’s red-light district. A small scandal erupted in late 1904– 5, when the rival paper, Rafu Mainichi, ran a large article attacking Rafu Shimpo founder Masaharu Yamaguchi and another editor under the headline “Elite Gentleman Buying Prostitutes.” The motive for the attack soon became apparent. Mainichi’s editor was not only a business rival, but also Yamaguchi’s rival for the affections of the same prostitute.

On weekend afternoons, when they were not working, drinking, or whoring, the young reporters played baseball. The team began in 1904, probably with informal pick- up games joined by whoever could be convinced to play. Soon, however, a true team coalesced, and players joined from outside the newspaper. An article in the Los Angeles Herald noted that the squad was calling itself the Japanese Base Ball Club of Los Angeles by May 17, 1905.

The team included Harase, the drinking partners Saito and Sato, and Tozan Masko. Twenty- five- year- old Takejiro Ito, one of the most respected men in Los Angeles’s Japanese community, became the club’s first president. From Chiba Prefecture, Ito graduated from Saisei Gakusha Medical School at just seventeen years old in 1895 and passed the national medical board two years later. In 1898 he immigrated to the United States and, after stints in Portland and Fresno, arrived in Los Angeles to open his own medical practice around 1903. Despite his education and stature in the community, Ito meshed well with his Rafu Shimpo teammates. A biographical entry noted that he was “very friendly to everyone, having relationships with people in all different social levels. He loves sake and was very energetic and never got a hangover.” As he got older, Ito would become known as a community organizer and patron of Japanese sports such as sumo, jiujitsu, and archery, as well as baseball.

Soon after arriving in Los Angeles in late 1905, Harry Saisho and Ken Kitsuse visited the Rafu Shimpo office, met with the ballplayers, and joined the team. Finding an open space to play ball near the newspaper offices was difficult. By 1904 office and industrial buildings covered most of downtown Los Angeles. The ballplayers would walk east on First Street, past the domed Santa Fe Railroad depot, across the First Street Bridge, to the open lots on East First Street, just west of Aliso Road and Boyle Ave. In the late 1880s to early 1890s the area held one of the city’s first baseball fields. Known as the Old First Street Grounds, the ballpark was owned and operated by Marco Hellman, the son of Isaias Hellman, a wealthy banker, real estate developer, and founder of the University of Southern California. No description of the ballpark survives, although we know that it had a grandstand shaded by canvas because two local boys stole the covering in August 1890. The park was closed in 1895, but maps show that sections remained undeveloped until after 1905. Each Sunday the members of the Japanese Base Ball Club of Los Angeles would meet at the open lot and practice or play against other amateur teams. According to an unidentified longtime resident, these games became “celebrated as a healthy form of entertainment in the Japanese community.”

The club was among the earliest Japanese immigrant baseball teams. The first teams emerged in Hawaii, where large numbers of Japanese had immigrated to work on the islands’ sugar plantations. In 1896 Reverend Takie Okumura, concerned about the moral and physical welfare of children left on their own while their parents toiled in the fields and mills, established a Japanese kindergarten and the Honolulu Japanese Elementary School. Three years later he organized his students into a baseball team called the Excelsiors. Although just youths, the Excelsiors are the first known all-Japanese team organized outside of Japan. Within a few years other Japanese youth teams, such as the Asahi, were created. Adult teams followed, and in 1908 the first Japanese baseball league was established in Honolulu with five teams. A decade later the Hawaiian Islands contained dozens of organized Japanese ball clubs at all levels, playing in both Japanese and multiethnic leagues.

On the mainland United States primary sources for early Japanese immigrant baseball are scarce— almost nonexistent. Few copies of Japanese immigrant newspapers prior to 1906 survive, and mainstream American newspapers mostly ignored Asian players and teams. As a result, there is no primary evidence of a Japanese immigrant team on the mainland prior to the Herald’s May 1905 reference to the Rafu Shimpo club. But oral tradition states that the first Issei team began in San Francisco when famed artist Chiura Obata founded the Fuji Athletic Club in the fall of 1903 and designed the team’s interlocking FAC logo. Tradition also states that the following year a group of young men from Kanagawa Prefecture organized the Kanagawa Doshi Club (kdc) in the Bay City.

Two reports of individual Japanese playing in the United States before May 1905 did reach the national press. On June 7, 1897, “Patsy” Tebeau, the player-manager of the Cleveland Spiders, whose outfield already included Native American Louis Sockalexis, sprung some choice news on a reporter from the Washington Post:

By the way, I forgot to tell you that we are going to enlarge the curio department of the Spiders. Sockalexis is the feature of our museum now, barring a necktie that Jack O’Connor brought in Boston and broke the Sabbath with. . . . Besides Sockalexis and Jack’s Sabbath breaking neckwear in our museum, I will place a five-foot- three Jap. This Jap is built like little Cub Stricker [the Cleveland infielder who stood 5 feet 3 and weighed 138 pounds] and is a relative of Sorakichi, the Japanese wrestler, who died a few years ago. He was brought to my attention by Pete Gallagher, the old catcher, who is now a politician in Chicago. Jap has played on amateur teams in Chicago. He is swift as a bullet and can hit in the .300 class, so Pete believes. He handles himself like a seasoned veteran. I will spring him on the public next season. These museum attractions on a ball team are boxoffice successes.

About a month later Sporting Life announced, “It is reported that Manager Tebeau of Cleveland has signed a new player in the person of a Japanese athlete and juggler, a half-brother to Matsuda Sorakichi, the famous wrestler. Tebeau thinks the Jap will be the marvel of the diamond and the greatest player of the century.”

Tebeau, however, did not follow through on his plan, and newspapers provide no more information on this mysterious Japanese ballplayer. His reported half- brother, Matsuda Sorakichi, was well known to most sporting fans in the 1880s. Born in 1859 in Japan, Matsuda was a trained sumo wrestler with the name Torakichi before emigrating to the United States in 1883 and becoming a professional wrestler. He wrestled throughout the Northeast and Great Lakes area, facing the world’s top wrestlers during his seven- year career. In 1885 he married Ella B. Lodge, a white American widow from Philadelphia, but the two would separate before Sorakichi died penniless on August 16, 1891. No record of Matsuda’s having a half-brother or other relatives in the United States has been found. It is, of course, highly possible that Tebeau, or his friend Pete Gallagher, claimed that the Japanese player was a relative of the famous wrestler to help publicize the prospect.

No other Japanese ballplayer would make the news until 1905, when Patsy Tebeau’s archrival John McGraw of the New York Giants reportedly tried to sign a Japanese. On February 10 the New York Times reported, “When the New York National League players start south on their training trip they will be accompanied by a Japanese ball player, who answers to the name of Shumza Sugimoto. He is twenty-three years old, an outfielder, and played last year with the Cuban Giants. While McGraw does not expect the Japanese to make the team, he has consented to take him South, and see what there is in him. Sugimoto is a jiu jitsu expert . . . [and] weighs only 118 pounds, but it is said can handle a man who tips the scales at 175.”

The next day the Elmira Gazette and Free Press added that Sugimoto was “a remarkable outfielder, a fine batter and skillful base runner [who] is likely to be put into regular service in center field.” Other publications picked up the news and added that Sugimoto “was a masseur at the Hot Springs, where McGraw found him and took him on the field to try him out. The little manager declared he was ‘all to the good.’”

Even if Sugimoto had the ability to make the Giants, his eligibility to play in the National League was in doubt. McGraw told the Sporting Life, “The question as to whether a Mongolian can play in the National League will be raised in time.” On February 25 the Oakland Tribune ran an article questioning the validity of barring Japanese. The article noted, “All this talk of drawing the color line on Sugimoto seems rather incongruous when one recalls the fact that Bender, Sockalexis and other Indians have been allowed to play in the big league.” Furthermore, “There is nothing in the by-laws and constitution of the National League which would prevent Sugimoto from making his appearance at the historic Polo Grounds.” Sugimoto seemed indignant that he could be barred from playing. Sporting Life reported that he “does not like the drawing of the color line in his case and says he will remain a semi-professional with the Creole Stars of New Orleans if his engagement by the Giants will be resented by the players of other clubs.”

Whether it was on account of race or ability, McGraw did not sign Sugimoto, and he disappears from the records. Attempts to trace his baseball career with the Cuban Giants and Creole Stars or his personal life have been fruitless. A tantalizing document, however, suggests his possible past. On March 10, 1904, the Louisiana, out of Havana, docked at New Orleans. Among the passengers was the Sugimoto Acrobat Troupe from Japan. During the voyage one of the troupe “was attacked in the hold of a steamship traveling from Havana to New Orleans by an infuriated panther. His cries for help were quickly answered, but not before he was terribly torn.” After disembarking, the Sugimoto Troupe joined the Great Floto Show, a traveling circus, and toured throughout the West and Louisiana. The troupe consisted of forty-four- year- old K. Sugimoto and his five sons, who ranged in age from eight to twenty-three. The eldest son, recorded in the passenger list as S. Sugimoto, born about 1881, would be the same age as Shumza Sugimoto, who would play ball in New Orleans. Although it is possible, it seems unlikely that there were two twenty-three-year-old athletes from Japan named S. Sugimoto living in the New Orleans area during the winter of 1904– 5.

Starting in April 1905, Japanese baseball was again in the news as Isoo Abe and his Waseda University Base Ball Club arrived in San Francisco with plans to tour the United States. It would be the first foreign team to play in America. The visit would transform both international and Japanese American baseball and change Saisho’s and Kitsuse’s lives.

End of excerpt.

A former archaeologist with a Ph.d. from Brown University, Rob Fitts left academics behind to follow his passion - Japanese Baseball. An award-winning author and speaker, his articles have appeared in numerous magazines and websites, including Nine, the Baseball Research Journal, the National Pastime, Sports Collectors Digest, and on MLB.com.

He is the author of five books on Japanese baseball. His latest book, Issei Baseball: The Story of the First Japanese American Ballplayers was just published by the University of Nebraska in April 2020. Earlier books include Mashi: The Unfulfilled Baseball Dreams of Masanori Murakami, the First Japanese Major Leaguer (University of Nebraska Press, 2015); Banzai Babe Ruth (University of Nebraska Press, 2012); Wally Yonamine: The Man Who Changed Japanese Baseball (University of Nebraska Press, 2008); and Remembering Japanese Baseball: An Oral History of the Game (Southern Illinois University Press, 2005).

Fitts is the founder of SABR's Asian Baseball Committee and recipient of the society's 2013 Seymour Medal for Best Baseball Book of 2012; the 2019 McFarland-SABR Baseball Research Award; the 2012 Doug Pappas Award for best oral research presentation at the Annual Convention; and the 2006 Sporting News- SABR Research Award. He has also been a finalist for the Casey Award and a silver medalist at the Independent Publish Book Awards.

While living in Tokyo in 1993-94, Fitts began collecting Japanese baseball cards. He is now recognized as one of the leading experts in the field and has created the ebusiness Robs Japanese Cards LLC. He regularly writes and speaks about the history of Japanese baseball cards and was a 2020 finalist for the Jefferson Burdick Award for Contributions to the Hobby.

Excerpted from Issei Baseball: The Story of the First Japanese American Baseball Players by Robert K. Fitts by permission of the University of Nebraska Press. ©2020 by Robert K. Fitts.

Howard Cole is a news and sports journalist in Los Angeles. Credits include Sports Illustrated, Forbes, Rolling Stone, LAT, OCR, Guardian, LA Weekly, Westways, VOSD, Prevention, Bakersfield Californian and Jewish Journal. Founding Director, IBWAA.