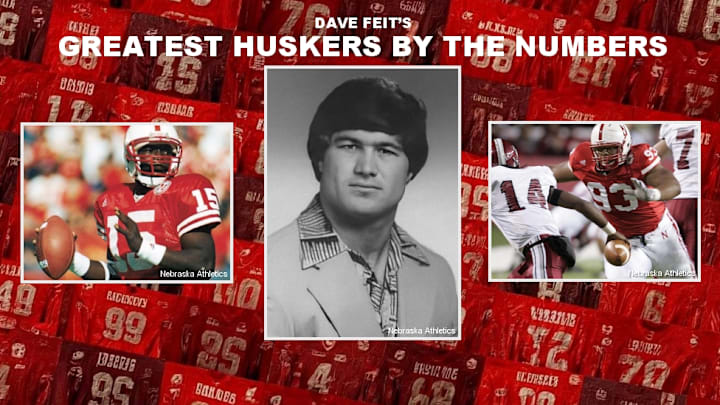

Dave Feit’s Greatest Huskers by the Numbers: 73 – Kelvin Clark

In this story:

Dave Feit is counting down the days until the start of the 2025 season by naming the best Husker to wear each uniform number, as well as one of his personal favorites at that number. For more information about the series, click here. To see more entries, click here.

Greatest Husker to wear 73: Kelvin Clark, Offensive Tackle, 1974 – 1978

Honorable Mention: Mark Behning, Marvin Crenshaw, Dan Hurley, Chris Mathis, Robert Pickens

Also worn by: Broc Bando, James Brown, Steve Engstrom, Pev Evans, Sam Hahn, Jared Helming, Dan Hurley, D.J. Jones, Tyler Moore, David Noonan, Fred Pollack

Dave’s Fave: Fred Pollack, Offensive Tackle, 1993 – 1997

“Champions are made when nobody’s watching.” – Boyd Epley

The early days of Husker Power were a time of growth, innovation and challenging convention. For example, Bob Devaney and Tom Osborne believed that the best way to condition football players before the season was running. Lots and lots and lots of running. One of the winter conditioning stations in 1968 was nothing but running for five minutes. Endurance training is great for cross country runners but isn’t the best approach for a football team.

Epley pointed out that most football plays last a handful of seconds, followed by 20-30 seconds of inactivity. Short, explosive bursts followed by quick recovery would better replicate game conditions. Lifts and exercises that generated power and force when pushing off the ground would matter more than running a mile.

Along the way, it became clear that the strength and conditioning needs of an offensive lineman would be vastly different from those of a receiver or cornerback. There was no need for offensive linemen to train like distance runners, and raw, brute strength was less important to a receiver than acceleration and change of direction. Position-specific exercises and lifts were developed and utilized throughout the entire calendar year.

In 1974, Nebraska became the first school to have an organized summer conditioning program with weightlifting. For those players who were not in Lincoln, a conditioning manual and logbook was printed so they could work out on their own. Players were asked to send postcards of their progress back to the coaching staff.

A copy of the 1978 summer conditioning book is archived online. Inside the 70+ pages is everything a player would need to know. It was meticulously laid out in the following sections:

- Warm-up and stretching – with diagrams on proper form.

- Form running – high knees, bounding, sprints, etc.

- “Skill and Drill” – position-specific drill work.

- Daily workout – Cardio and conditioning.

- Weight training – More diagrams to ensure injury-free technique.

- Cool down – A light jog and stretching.

- Nutrition – Meal plans for bulking up or slimming down.

At the time, summer conditioning was unheard of. Coaches believed summers were a time for resting the bodies or working a job. What few realized was that those summer jobs were often a summer conditioning program of their own. There were countless examples of players from previous eras who unintentionally gained great strength and endurance by doing manual labor jobs all summer long.

The lore around Nebraska natives has been the “beefy, corn-fed players,” when the reality is the many farm kids who grew up stacking hay bales and other manual jobs were essentially working out on their own. City kids knew hard work as well. In the late 1930s, Forrest Behm unloaded bags of sugar beets from a train and stacked them floor to ceiling in a warehouse.*

*That was his night job. During the days, he shoved concrete on the road now known as Cornhusker Highway. Stay tuned for Behm’s entry. It’s unbelievable.

By 1978, Summer Conditioning was a class available for college credit. The program included a taper-down phase to prepare players for camp and the regular season. The lifting did not stop when the games started. Epley pioneered in-season workouts as well.

The desire to innovate and maximize the student athletes’ potential was a driving force for Epley and Husker Power. As other schools saw Nebraska’s success and tried to replicate it and/or hire his staff,* Epley strived to always stay a step ahead of the rest of the sport, as that would keep Nebraska’s edge. He invented techniques and lifts, exercises and equipment, and regiments and evaluations to see his success. Yes, there was definitely some trial and error involved, but the overall results spoke for themselves.

*In 1976, Epley accepted a job to be the first strength and conditioning coach of the Detroit Lions, but Tom Osborne convinced Epley to stay.

Speaking of results, let’s talk about Kelvin Clark. Clark was an outstanding prep tackle in Odessa, Texas, with a 6-foot-4 frame. But he was reportedly 215 pounds as a college freshman in 1974 with a 40-yard dash time of 5.1 seconds. He did what so many other players – especially linemen – did during the Osborne era: He poured himself into Epley’s weight training program and worked on his technique with line coach Milt Tenopir. As a 230-pound sophomore, Clark played behind Bob Lingenfelter,* an All-Big Eight pick and honorable mention All-American. By his junior year (1977), Clark was up to 250 pounds and was starting at tackle.

*A photo of Bob Lingenfelter’s little brother Bruce was the inspiration for the Husker Power logo. The original logo was later tweaked to show the updated form for the lift.

As a senior in 1978, Clark had bulked up to 275, most of it pure muscle. He was voted “Weightlifter of the Year” by his teammates. His time in the 40 was down to 4.85 seconds. Clark was the left tackle on a line that helped Nebraska gain 501 yards of total offense, 337 yards rushing, and score 38 points per game. Tom Osborne beat Oklahoma for the first time in 1978, with Clark making excellent blocks on both of Nebraska’s touchdowns.

Clark was All-Big Eight and a consensus All-American. After the season, Osborne said Clark was “possibly the best offensive lineman ever to play at Nebraska.” Sure, that was said prior to the careers of Nebraska’s Outland Trophy-winning linemen, but it is still some high praise.

Meanwhile, Boyd Epley kept innovating and trying to stay ahead of the pack. When the Huskers played in a bowl game, it was not uncommon for Epley to have weightroom equipment trucked to the bowl site. He worked with manufacturers to develop new machines to isolate the muscle groups used in specific football moves. Nebraska’s weight room kept expanding as well. In 1981, NU had the largest weight room in the world (13,300 sq. ft., approximately twice the size of what Oklahoma had). Today, the weightroom in Nebraska’s new football complex is over 32,000 sq. ft.

In a 2010 ESPN article, Epley was named as “arguably the single most important individual in the history of strength and conditioning in college athletics.” Over 55,000 certified strength and conditioning coaches owe their careers to him and the industry he pioneered. Epley founded the National Strength and Conditioning Association in 1978, with 76 charter members. Their inaugural event was held in Lincoln. The entertainment was provided by Kelvin Clark, who sang for the audience.

***

“It was the weight room… that’s where it starts. To physically become stronger and dominate people physically, the weight room was the place where you went to improve, it’s where boys came to become men… That was the reality of it: we could hit you longer and harder and faster than the average team because we paid the price in that weight room.”

– former Husker split end Aaron Davis, (from Paul Koch’s “Anatomy of an Era“)

I was tempted to make Kelvin Clark my personal favorite solely based on his nickname “Big Neck.” Instead, I’m going with Freddy Pollack, part of some of the greatest offensive lines in school history. The odds are good that before we’re done, I’ll pick every single offensive lineman from 1994 to 1997 as a favorite. Sue me, I loved the dominance of the mid-’90s run game, and those offensive lines were a big reason it was so successful.

There was something so primally gratifying about watching Nebraska’s offensive line and backs break the spirit of a defense over the course of a game.

First quarter: The opposing defense would show off some new wrinkle designed to thwart Nebraska’s option and power running game. They’d get some tackles for loss and a few stops. But Nebraska, like a worker with a sledgehammer, would just keep swinging away.

Second quarter: Osborne and his staff didn’t wait for halftime to adjust. Most of the time, they didn’t need to. With most opponents, cracks were already starting to show in the defensive wall. The offense would continue to hammer away with 12-play, 80-yard scoring drives, converting third downs and keeping the defense on the field.

Third quarter: Nebraska’s I-backs didn’t need much. A small crevice or gap would be enough to burst for 15 yards – or more. Against an outmanned opponent (the Iowa States, Kansas schools and nonconference foes), the game would be out of reach in the third quarter and the backups would get their time to develop and shine.

Fourth quarter: Even in close games, the fourth quarter belonged to Nebraska. The Huskers' superior strength and conditioning would be too much for opposing defenses. A play that went for four yards in the first quarter would now go for 14 … or 40. Key on the quarterback or the I-back, then watch as a walk-on fullback from a tiny Nebraska town rumbled for a first down. Defensive backs, tired of getting knocked down by split ends all day long, would be ready to call it a day. Then, NU would hit a play-action pass over the top of them.

That level of domination didn’t just happen. It took months and years of hard work and dedication. It was cultural. Fred Pollack can attest to that. A scholarship recruit from Omaha’s Creighton Prep High School, Pollack was a finalist for Nebraska’s Lifter of the Year Award in 1996 and 1997. He set position records for strength and speed.

Pollack played in 35 games over his career but didn’t start until his senior year (1997). He piled up 102 pancake blocks, including 17 in the classic overtime win at Missouri. He earned honorable mention All-Big 12 honors at left tackle.

TV announcers and national writers used to marvel at how Nebraska was able to “reload” on offense year after year. The secret was the established culture of hard work, a dedication to the weight room, and the practice reps to gain mastery of their craft.

And it showed with guys like Fred Pollack who were willing to pay the price to start for a single, championship-winning team.

More from Nebraska on SI

Stay up to date on all things Huskers by bookmarking Nebraska Cornhuskers On SI, subscribing to HuskerMax on YouTube, and visiting HuskerMax.com daily.

Dave Feit is counting down the days until the start of the 2025 season by naming the best Husker to wear each uniform number, as well as one of his personal favorites at that number. For more information about the series, click here. To see more entries, click here.

Greatest Husker to wear 73: Kelvin Clark, Offensive Tackle, 1974 – 1978

Honorable Mention: Mark Behning, Marvin Crenshaw, Dan Hurley, Chris Mathis, Robert Pickens

Also worn by: Broc Bando, James Brown, Steve Engstrom, Pev Evans, Sam Hahn, Jared Helming, Dan Hurley, D.J. Jones, Tyler Moore, David Noonan, Fred Pollack

Dave’s Fave: Fred Pollack, Offensive Tackle, 1993 – 1997

“Champions are made when nobody’s watching.” – Boyd Epley

The early days of Husker Power were a time of growth, innovation and challenging convention. For example, Bob Devaney and Tom Osborne believed that the best way to condition football players before the season was running. Lots and lots and lots of running. One of the winter conditioning stations in 1968 was nothing but running for five minutes. Endurance training is great for cross country runners but isn’t the best approach for a football team.

Epley pointed out that most football plays last a handful of seconds, followed by 20-30 seconds of inactivity. Short, explosive bursts followed by quick recovery would better replicate game conditions. Lifts and exercises that generated power and force when pushing off the ground would matter more than running a mile.

Along the way, it became clear that the strength and conditioning needs of an offensive lineman would be vastly different from those of a receiver or cornerback. There was no need for offensive linemen to train like distance runners, and raw, brute strength were less important to a receiver than acceleration and change of direction. Position-specific exercises and lifts were developed and utilized throughout the entire calendar year.

In 1974, Nebraska became the first school to have an organized summer conditioning program with weightlifting. For those players who were not in Lincoln, a conditioning manual and logbook was printed so they could work out on their own. Players were asked to send post cards of their progress back to the coaching staff.

A copy of the 1978 summer conditioning book is archived online. Inside the 70+ pages are everything a player would need to know. It was meticulously laid out in the following sections:

- Warm-up and stretching – with diagrams on proper form.

- Form running – high knees, bounding, sprints, etc.

- “Skill and Drill” – position-specific drill work.

- Daily workout – Cardio and conditioning.

- Weight training – More diagrams to ensure injury-free technique.

- Cool down – A light jog and stretching.

- Nutrition – Meal plans for bulking up or slimming down.

At the time, summer conditioning was unheard of. Coaches believed summers were a time for resting the bodies or working a job. What few realized was that those summer jobs were often a summer conditioning program of their own. There were countless examples of players from previous eras who unintentionally gained great strength and endurance by doing manual labor jobs all summer long.

The lore around Nebraska natives has been the “beefy, corn-fed players,” when the reality is the many farm kids who grew up stacking hay bales and other manual jobs were essentially working out on their own. City kids knew hard work as well. In the late 1930s, Forrest Behm unloaded bags of sugar beets from a train and stacked them floor to ceiling in a warehouse.*

*That was his night job. During the days, he shoved concrete on the road now known as “Cornhusker Highway.” Stay tuned for Behm’s entry. It’s unbelievable.

By 1978, Summer Conditioning was a class available for college credit. The program included a taper down phase to prepare players for camp and the regular season. The lifting did not stop when the games started. Epley pioneered in-season workouts as well.

*In 1976, Epley accepted a job to be the first strength and conditioning coach of the Detroit Lions, but Tom Osborne convinced Epley to stay.

Speaking of results, let’s talk about Kelvin Clark. Clark was an outstanding prep tackle in Odessa, Texas with a 6-4 frame. But he was reportedly 215 pounds as a college freshman in 1974 with a 40-yard dash time of 5.1 seconds. He did what so many other players – especially linemen – did during the Osborne era: he poured himself into Epley’s weight training program and worked on his technique with line coach Milt Tenopir. As a 230-pound sophomore, Clark played behind Bob Lingenfelter,* an All-Big Eight pick and honorable mention All-American. By his junior year (1977), Clark was up to 250 pounds and was starting at tackle.

*A photo of Bob Lingenfelter’s little brother Bruce was the inspiration for the Husker Power logo. The original logo was later tweaked to show the updated form for the lift.

As a senior in 1978, Clark had bulked up to 275, most of it pure muscle. He was voted “Weightlifter of the Year” by his teammates. His time in the 40 was down to 4.85 seconds. Clark was the left tackle on a line that helped Nebraska gain 501 yards of total offense, 337 yards rushing, and score 38 points per game. Tom Osborne beat Oklahoma for the first time in 1978, with Clark making excellent blocks on both of Nebraska’s touchdowns.

Clark was All-Big Eight and a consensus All-American. After the season, Osborne said that Clark was “possibly the best offensive lineman ever to play at Nebraska.” Sure, that was said prior to the careers of Nebraska’s Outland Trophy winning linemen, but it is still some high praise.

Meanwhile, Boyd Epley kept innovating and trying to stay ahead of the pack. When the Huskers played in a bowl game, it was not uncommon for Epley to have weightroom equipment trucked to the bowl site. He worked with manufacturers to develop new machines to isolate the muscle groups used in specific football moves. Nebraska’s weight room kept expanding as well. In 1981, NU had the largest weight room in the world (13,300 sq. ft., approximately twice the size of what Oklahoma had). The weightroom in the Nebraska’s new football complex is over 32,000 sq. ft.

In a 2010 ESPN article, Epley was named as “arguably the single most important individual in the history of strength and conditioning in college athletics.” Over 55,000 certified strength and conditioning coaches owe their career to him and the industry he pioneered. Epley founded the National Strength and Conditioning Association in 1978, with 76 charter members. Their inaugural event was held in Lincoln. The entertainment was provided by Kelvin Clark, who sang for the audience.

***

“It was the weight room… that’s where it starts. To physically become stronger and dominate people physically, the weight room was the place where you went to improve, it’s where boys came to become men… That was the reality of it: we could hit you longer and harder and faster than the average team because we paid the price in that weight room.”

“It was the weight room … that’s where it starts. To physically become stronger and dominate people physically, the weight room was the place where you went to improve, it’s where boys came to become men … That was the reality of it: we could hit you longer and harder and faster than the average team because we paid the price in that weight room.”

– former Husker split end Aaron Davis, (from Paul Koch’s “Anatomy of an Era“)

I was tempted to make Kelvin Clark my personal favorite solely based on his nickname “Big Neck.” Instead, I’m going with Freddy Pollack, part of some of the greatest offensive lines in school history. The odds are good that before we’re done, I’ll pick every single offensive lineman from 1994 – 1997 as a favorite. Sue me, I loved the dominance of the mid-90s run game, and those offensive lines were a big reason why it was so successful.

There was something so primally gratifying about watching Nebraska’s offensive line and backs break the spirit of a defense over the course of a game.

First quarter: The opposing defense would show off some new wrinkle designed to thwart Nebraska’s option and power running game. They’d get some tackles for loss and a few stops. But Nebraska, like a worker with a sledgehammer, would just keep swinging away.

Second quarter: Osborne and his staff didn’t wait for halftime to adjust. Most of the time, they didn’t need to. With most opponents, cracks were already starting to show in the defensive wall. The offense would continue to hammer away with 12-play, 80-yard scoring drives, converting third downs and keeping the defense on the field.

Third quarter: Nebraska’s I-Backs didn’t need much. A small crevice or gap would be enough to burst for 15 yards – or more. Against an out-manned opponent (the Iowa States, Kansas schools and nonconference foes), the game would be out of reach in the third quarter and the backups would get their time to develop and shine.

Fourth quarter: Even in close games, the fourth quarter belonged to Nebraska. Their superior strength and conditioning would be too much for opposing defenses. A play that went for four yards in the first quarter would now go for 14… or 40. Key on the quarterback or the I-Back, then watch as a walk-on fullback from a tiny Nebraska town rumbled for a first down. Defensive backs, tired of getting knocked down by split ends all day long, would be ready to call it a day. Then, NU would hit a play action pass over the top of them.

That level of domination didn’t just happen. It took months and years of hard work and dedication. It was cultural. Fred Pollack can attest to that. A scholarship recruit from Omaha’s Creighton Prep High School, Pollack was a finalist for Nebraska’s Lifter of the Year Award in 1996 and 1997. He set position records for strength and speed.

Pollack played in 35 games over his career, but didn’t start until his senior year (1997). He piled up 102 pancake blocks, including 17 in the classic overtime win at Missouri. He earned honorable mention All-Big 12 honors at left tackle.

TV announcers and national writers used to marvel at how Nebraska was able to “reload” on offense year after year. The secret was the established culture of hard work, a dedication to the weight room, and the practice reps to gain mastery of their craft.

More from Nebraska on SI

Stay up to date on all things Huskers by bookmarking Nebraska Cornhuskers On SI, subscribing to HuskerMax on YouTube, and visiting HuskerMax.com daily.

Dave Feit began writing for HuskerMax in 2011. Follow him on Twitter (@feitcanwrite) or Facebook (www.facebook.com/FeitCanWrite)