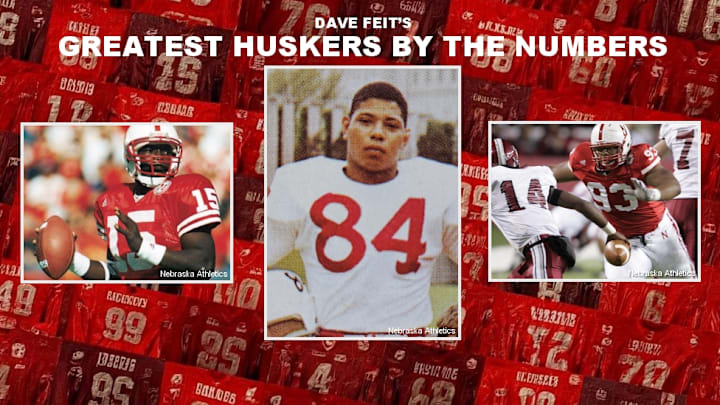

Dave Feit’s Greatest Huskers by the Numbers: 84 – Tony Jeter

In this story:

Dave Feit is counting down the days until the start of the 2025 season by naming the best Husker to wear each uniform number, as well as one of his personal favorites at that number. For more information about the series, click here. To see more entries, click here.

Greatest Husker to wear 84: Tony Jeter, End, 1963 – 1965

Honorable Mention: Willie Griffin, Donta Jones, Mike Rucker, Tim Smith

Also worn by: Jon Bowling, Alex Bullock, Sam Cotton, Dale Didur, Don Hewitt, Dan Hill, Miles Kimmel, Brandon Kinnie, Grant Mulkey, Jordan Ober, Dave Redding, Gregg Reeves, Xavier Rucker, Rick Wendland

Dave’s Fave: Mike Rucker, Rush End, 1994 – 1998

Last time, we talked about the “Magnificent Eight,” a group of eight black players on the 1964 Nebraska team.

There are two important things we need to discuss with those eight players and the others who followed in their footsteps: how they got to Nebraska, and how they were treated once they arrived. Remember: the early and mid-1960s were a turbulent time in our nation’s history. The quest for equal rights was strong, but so were the stubborn, ignorant ways of the past.

Let’s start with how black players were treated when they arrived at the University of Nebraska. I’d love to be able to tell you that every black player was welcomed with open arms by their white teammates and campus classmates (many of whom, from smaller Nebraska towns, may not have ever met a black person before).

But we all know that wasn’t the reality of being a black man in the 1960s. As All-American guard Bob Brown once said: “There were some things yelled from cars. But cowards do cowardly things.”

I will tell you that Bob Devaney did not tolerate racism on this teams or racist treatment of his players. There are two famous examples of this:

In 1963, Nebraska earned an invitation to the Orange Bowl in Miami. Upon arriving at the team hotel, the manager told Devaney that his black players would have to stay somewhere else. Devaney agreed that the black players would stay somewhere else… and the white players would too. He promptly moved the entire team to a different hotel. His Cornhuskers would stay together.

On the 1969 team, four of the five starting defensive linemen were black. This led to some murmurs in the locker room. Defensive line coach Monte Kiffin stopped it cold. He had the starters stand at the front of the room and proclaimed, “If anybody can beat them out, beat them out. That’s the only way you’re going to start.” Playing time was about merit, not skin tone. Put up or shut up.

***

We will dive deeper into this topic later on, but Devaney focused his recruiting efforts in two primary places: Nebraska (particularly, Omaha) and the Big Ten footprint. Devaney landed numerous players – both white and black – from these areas.

But today we’re going to focus on Devaney’s recruitment of black players. Preston Love, another member of the Magnificent Eight and a graduate of Technical High School in Omaha, described Bob Devaney as “a pioneer” in this regard.

Bob Devaney did not shy away from recruiting black players to Nebraska. He embraced it. In north Omaha, where the neighborhood understood the reasons Gale Sayers went to Kansas, Devaney had to make inroads and build relationships. He put in the work, connected with parents and backed up his promises.

As Omaha players saw Devaney recruit – and play – their friends and classmates, the recruiting wins started to snowball. The successes of the Magnificent Eight helped Devaney sign two of the best players from Omaha – Mike Green from Tech and Dick Davis from North. In turn, Green was influential in persuading another Tech High graduate – Johnny Rodgers – to come to Lincoln. Although Devaney himself made a pretty convincing promise to keep Rodgers from heading to USC.

At a 2019 event, Johnny Rodgers recounted a vow that Devaney made to him: “Bob told me he was going to recruit more black players than anybody ever had, and he was going to let them play. And that’s what he went on to do.”

Devaney’s greatest gifts – his disarming personality and quick, self-effacing wit – helped him relate in both black and white living rooms all around the country. Many coaches would shy away from venturing into black neighborhoods for recruiting; they preferred to meet players at the high school. Devaney didn’t care. He went to where the players were and connected with them and their families. There is a classic Devaney recruiting story that is the perfect example of this.

Devaney was sitting in the living room of a humble West Virgina apartment. The mother of the recruit sat at the piano and played the old hymn “Bringing in the Sheaves.” She stopped, and asked Devaney a question:

“Is it true, that you have gone so far as to sing hymns with a mother to get her boy to go to Nebraska?”

“Yes, I did that,” Devaney replied. “The mother came to Nebraska and the boy enrolled at Missouri.”

In this case, the recruit – who initially wanted to go to Arizona State – ended up in Lincoln.

His name was Tony Jeter.

At Nebraska, Jeter started all 33 games of his varsity career. In 1963 (his first on varsity), he was the team’s leading receiver on a very run-heavy team (nine catches for 151 yards). At Minnesota, Jeter caught a 65-yard fourth-quarter touchdown that turned out to be the game winner. In 1964, he earned All-Big Eight honors.

As a senior in 1965, Jeter was once again named first-team All-Big Eight. He ended up with a career receiving line of 38 catches for 528 yards and one TD.*

*A reminder that old statistics do not include bowl games, which is a shame because Jeter had two touchdowns in his final game, the 1966 Orange Bowl against Alabama.

At the end of the 1965 season, Jeter was a named a first-team All-American. He was also honored as an Academic All-American, making him the first black player at Nebraska to earn that prestigious recognition.

Tony Jeter was drafted by the Green Packers and attended training camp with his older brother Bobby (an All-American at Iowa). However, Tony was traded to Pittsburgh before the season started.

***

In early November 1997, my buddy Mark and I left Lincoln on a road trip. We drove down to Emporia, Kansas, to pick up two more friends. Our destination? Columbia, Missouri. We had tickets to watch top-ranked Nebraska play the Missouri Tigers.

We had great seats in the Nebraska section in the southwest corner of the stadium. We settled in, expecting another blowout – the Huskers had won their first five Big 12 games by an average score of 48-11.

Mizzou went right down the field and scored. Scott Frost scored on a pair of first-quarter touchdown runs to give NU a 21-7 lead.

But the Tigers kept battling back. They took advantage of defensive lapses and Husker turnovers to take a 24-21 lead at halftime. Mizzou fans started chirping at us, but we weren’t worried.

The teams traded touchdowns in the third quarter. Nebraska was moving the ball (the Huskers had 528 yards of total offense) but turned it over three times. Missouri quarterback Corby Jones was playing an amazing game. He made big play after big play, accounting for 293 yards of total offense and four touchdowns. The fourth came with just 4:39 left in the game and put Mizzou ahead 38-31.

On the ensuing drive, Nebraska gained six yards on three plays. The Huskers had to punt with 3:31 left. The Tigers gained a first down and we exchanged nervous looks. At this point in my life, I had been to almost 40 Nebraska games and had never seen the Huskers lose in person. If Mizzou got another first down, that streak would end.

But the Blackshirts stood tall. They got three straight stops, and Tom Osborne used all three of his timeouts. Bobby Newcombe returned the Tiger punt 17 yards to the 33. There was 1:02 left on the clock.

Two things are true about that final drive. 1) Scott Frost deserves all of the credit for driving the Huskers 67 yards in 62 seconds. 2) This was not Frost’s best passing day. He threw 10 passes on the final drive. Five were incomplete. Two of the completions – both to Kenny Cheatham – were thrown low, which kept Cheatham from getting out of bounds to stop the clock. Despite it all, Nebraska had a chance.

Third-and-10 from the Tiger 12-yard line. Seven seconds left on the clock. You’ve seen the replay a million times, so here is what we saw from our seats in the opposite end of the field:

Frost drops back and rifles a ball over the middle to Shevin Wiggins. Wiggins falls backwards into the end zone. The home crowd goes nuts and fans start pouring onto the field. Deflation sets in as we realize Nebraska has just los…. wait! Matt Davison is holding the ball over his head. THE REF IS SIGNALING TOUCHDOWN!?! WHAT JUST HAPPENED???*

*In 1997, Missouri did not have any replay screens in their stadium. The first iPhone would not be released for another decade. We had no idea happened on the “flea kicker” play until we had driven back to our friends’ place in Emporia. We saw it on SportsCenter with our jaws on the floor.

The officials and stadium personnel cleared the students off the field. As Kris Brown lined up to kick the crucial PAT, the goalpost was still swaying from the fans that were just attempting to tear it down. Brown’s kick was perfect, and Nebraska was heading to its first-ever overtime game.

Missouri won the toss and chose to go on defense. Nebraska scored in three plays. I have heard that the ABC stations in Nebraska were just coming back from commercial when Frost scored from 12 yards out. On defense, Corby Jones’s magic finally ran out. Two incomplete passes and a three-yard scramble set up a do-or-die fourth down. Grant Wistrom and Mike Rucker – two Missouri natives who both turned down the Tigers to play for Nebraska – met at the quarterback, sacking Jones to end the game. It was the second sack of the game for each player.

Nebraska’s national championship hopes were still alive.

Mike Rucker was one of my favorite players of that era. Although he never earned the accolades of Wistrom, Jared Tomich, Trev Alberts and others, Rucker is one of the best rush ends to ever play at Nebraska. Possessing a dangerous combination of speed and power, he was a force on the edge – and not too shabby as a blocker on the punt return team.

Rucker finished his Husker career with 17 sacks, 40 tackles for loss and 36 quarterback hurries. He went on to have a lengthy and successful career with the Carolina Panthers.

More from Nebraska on SI

Stay up to date on all things Huskers by bookmarking Nebraska Cornhuskers On SI, subscribing to HuskerMax on YouTube, and visiting HuskerMax.com daily.

Dave Feit began writing for HuskerMax in 2011. Follow him on Twitter (@feitcanwrite) or Facebook (www.facebook.com/FeitCanWrite)