Book Excerpt: Bob Gibson's Experience with Racial Injustice in the 1960's

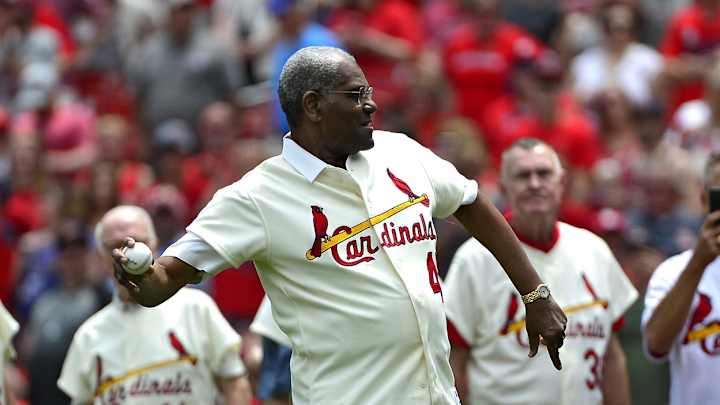

It's been a sad couple of days for baseball fans, and especially so for those of a certain age, raised on our national pastime during the 1960s. The Dodgers lost two of their own; Ron Perranoski on Saturday and "Sweet" Lou Johnson on Friday. Cardinals' fans, and those with an appreciation of historically-great pitching, were struck with the passing of Hall of Fame right-hander, Bob Gibson.

The Dodgers televised neither their home games nor their games from St. Louis in the 60's, so all we got to see of players like Gibson was the All-Star Game, the occasional Game of the Week, with Curt Gowdy and Tony Kubek and of course, the daytime-only World Series. Which was more than enough to impress young fans like me, and pretty much every friend I had. And still have. No doubt like you, my memories of Gibson center on both the 1967 and 1968 World Series, and 1968 -- the Year of the Pitcher -- in particular.

There is more to the man that just the on-field accomplishments, of course. And I wanted to share a bit with you here. I can personally recommend both the excerpt I've included about Gibson today, and the entirety of this fascinating book to you. It's "One Nation Under Baseball: How the 1960s Collided with the National Pastime" by John Florio and Ouisie Shapiro (April 2017, University of Nebraska Press, $9.99 Kindle, $14.64 paperback).

Florio describes the book this way:

"One Nation Under Baseball explores the intersection between American society and America’s pastime during the 1960s. It looks at the central issues -- race relations, the role of the press, and the labor wars between the players and the owners -- and reveals the events that reshaped the game.

"The decade was rich with memorable events. We spoke with insiders like Bill White and Elston Howard’s widow, Arlene, about the Jim Crow laws in Florida that segregated black players during spring training. Civil rights leader Andrew Young gave us a firsthand account of what it took for the city of Atlanta, determined to set itself apart from the backward South, to attract Henry Aaron and the Milwaukee Braves.

"We also look at the assassinations of JFK, RFK, and MLK through the eyes of ballplayers who were deeply affected by the events. Mudcat Grant had met John Kennedy in 1960 and was devastated when he heard the news of Kennedy’s death. Bob Gibson reacted to Dr. King’s murder by channeling his fury onto opponents during the ’68 season. Don Drysdale, who’d had a personal connection to Robert Kennedy, took his death to heart.

"We also cover fascinating stories featuring lesser-known names. George Gmelch was a minor-league prospect for the Tigers when he was called to the draft board. Fearing deployment to Vietnam, he and two other players schemed to flunk their physicals. And Michael Feinberg, who as a teenager worked as a vendor at Shea Stadium, smoked pot with John Lennon in the dressing room before the Beatles went on stage.

"The bad boy of the decade, [the late] Jim Bouton, [told] us how he threw the sport into chaos with baseball’s first tell-all. 'Ball Four' shook the game to its core; no one was more shaken than Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, who did his best to censor the book. Bouton’s recollection of his encounter with Kuhn the day he was summoned to the commissioner’s office is both hilarious and disturbing."

Below is an excerpt about Gibson, from Chapter 15:

The deaths of Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy struck the Cardinals’ Bob Gibson especially hard. He and millions of other black Americans had looked to the two leaders as their best hopes for achieving racial justice.

For Gibson, it had been a long time coming.

He’d grown up in the projects in Omaha, Nebraska, with his widowed mother and six siblings. Until Gibson’s senior year at Omaha Technical High School, his skin color was considered too dark for the baseball team. So he turned to basketball, became the team’s first black player, and showed so much promise that he set his sights on playing hoops at Indiana University. But prejudice cut him down again when Indiana informed him that the school had already reached its quota of black players: one. Undeterred, Gibson stayed in his hometown and became the first black athlete to receive a basketball scholarship from Creighton University. As a star at Creighton, he broke every school scoring record.

After college, Gibson was still undecided between basketball and baseball, so he signed with the Harlem Globetrotters and the St. Louis Cardinals. He eventually chose baseball and made the Majors in 1959, which is when he ran into Cardinals manager and unabashed bigot Solly Hemus.

Aside from calling Gibson and other black players “nigger” as a motivating tool, the thirty-six-year-old Hemus told the young Gibson he wasn’t big-league material. He even suggested that going over opposing hitters was beyond his intellectual scope. Just when Gibson was on the verge of quitting, he got some career advice from batting coach Harry Walker.

“It wasn’t much,” Gibson recalled, “but it hit the right chord. [Walker told me], ‘Hang in there, kid. Hemus will be gone long before you will.’”

Sure enough, Hemus was fired in the middle of the ’61 season, replaced by coach Johnny Keane (who would be replaced by Red Schoendienst in 1965). Keane didn’t give a damn about color. Upon taking over the reins, he gave his full support to black players, most notably Curt Flood, Bill White, and Gibson. With his manager’s encouragement, Gibson steadily blossomed into one of the game’s elite pitchers, finishing the 1963 season with an 18-9 record and 3.39 ERA. In the 1964 World Series, he beat the Yankees twice. In the 1967 Series against the Red Sox, he was nearly untouchable, hurling three complete-game victories and striking out twenty-six batters in twenty-seven innings.

But Gibson’s elevated stature in baseball earned him little respect outside the game. Vandals still pelted his house with bottles and eggs in an effort to drive him and his wife, Charline, out of their West Omaha neighborhood. Which is why, on the day that Martin Luther King was assassinated, Gibson was inconsolable.

Cardinals catcher Tim McCarver was quoted in Gibson’s 1996 memoir, Stranger to the Game.

Probably the last person he wanted to talk to that morning was a white man from Memphis, of all places. But I confronted him on that. . . . I told him that I had grown up in an environment of severe prejudice, but if I were any indication, it was possible for people to change their attitudes. . . . He didn’t really want to be calmed down and told me in so many words that it was plainly impossible for a white man to completely overcome prejudice. I said that he was taking a very nihilistic attitude and that just because some white people obviously maintained their hatred for blacks and considered them inferior, it was senseless to embrace a viewpoint that would lead nowhere.

The good news for the Cardinals was that Gibson channeled his fury into his pitches.

“You wouldn’t see him talk to the other players at all,” Schoendienst told Sports Illustrated. “It seemed like he just hated them. He said, ‘I ain’t going to get friendly with anybody.’”

The result was pure intimidation: a flamethrower with a scowl as nasty as his pitching arsenal.

“It was said that I threw, basically, five pitches,” Gibson wrote in his memoir. “Fastball, slider, curve, change-up, and knockdown. I don’t believe that assessment did me justice, though. I actually used about nine pitches—two different fastballs, two sliders, a curve, change-up, knockdown, brushback, and hit-batsman.”

Gibson started the 1968 season strong but had so little run support that he soon found himself with a losing record (4-5) despite his 1.66 ERA. On June 6, against the Astros, his team’s offense became a moot point. Gibson fired a shutout—and then did the same against the Braves, the Reds, and the Cubs.

“Without a doubt, I pitched better angry,” Gibson wrote. “I suspect that the control of my slider had more to do with it than anything, but I can’t completely dismiss the fact that nobody gave me any shit whatsoever for about two months after Bobby Kennedy died.”

At the end of June, he four-hit the Pirates and ran his shutout streak to five, putting him one shy of Drysdale’s mark. Sportswriters asked him whether he felt pressure trying to catch the Dodger ace.

“I face more pressure every day just being a Negro,” he said.

Gibson wasn’t alone. By the mid-’60s, black athletes were becoming increasingly vocal about racial inequality—and writing about it in autobiographies, such as Frank Robinson’s My Life in Baseball, Orlando Cepeda’s My Ups and Downs in Baseball, and Gibson’s first, From Ghetto to Glory.

At the same time, Sports Illustrated came out with a special series on the black athlete, in which it exposed the inequalities lurking in boxing rings, baseball dugouts, basketball benches, football huddles—and just about every other playing field. Black athletes, the magazine reported, were excluded from social activities on college campuses, taunted with racial slurs in professional arenas, subjected to tokenism in most sports, and regarded as lacking intellect across the board.

The popular press—Life, Time, Newsweek, U.S. News and World Report— took up the issue as well, running stories on Harry Edwards, an instructor at San Jose State, who was mobilizing black athletes into boycotting the upcoming Olympics in Mexico City. The group’s goal was to draw attention to the exploitation of black athletes in the United States and abroad. It called for, among other things, the reinstatement of Muhammad Ali’s heavyweight title, the hiring of more black coaches, and the removal of Nazi sympathizer Avery Brundage as head of the International Olympic Committee.

According to founding Chipmunk George Vecsey, “the first generation of black players all had to be Sidney Poitier; they all had to be the good Negro, the man who came to dinner, Jackie Robinson included. But there was another generation of black players; the core of the Cardinals in the mid-Sixties was black: Bob Gibson. Curt Flood. Lou Brock. They were all college guys. They had their opinions. These guys were taking on the role of teachers and shit-stirrers.”

On July 1, Gibson took the mound looking to break Drysdale’s scoreless-inning streak. The Cards were in Los Angeles, and Gibson was facing none other than Drysdale himself.

The suspense ended quickly. With two outs in the bottom of the first, Gibson gave up back-to-back singles. Then, with runners on first and third, he threw a fastball that tailed inside, surprising backup catcher Johnny Edwards. The ball skipped off Edwards’s glove, allowing a run to score. It was the first run Gibson had surrendered in a month, and the only one he’d give up in the game. His streak had ended at forty- seven innings, but he beat the Dodgers and raised his record to 10-5.

Gibson wouldn’t stop there. He’d go on to have one of the greatest seasons in baseball history. Displaying complete mastery of the craft of pitching—and riding his anger over the dual losses of King and Kennedy—he’d finish twenty-eight of his thirty-four starts. He’d compile a 22-9 record, 268 strikeouts, and a 1.12 ERA—the lowest in more than half a century.

“It was otherworldly,” says Tim McCarver, looking back on Gibson’s 1968 performance. “It staggered the imagination that during one stretch a guy pitched ninety-five innings and gave up two runs. He had eight shutouts in ten starts. . . . Keep in mind, every team had not only two or three, but in some cases four or five guys who could pummel you. . . . That season, [Gibson] could throw a ball to a spot no more than two balls wide, at will. Almost blindfolded. You can’t make 1968 bigger than it was.”

The Cardinals would ride Gibson’s golden right arm to the National League pennant, nine games ahead of the San Francisco Giants.

Howard Cole has been writing about baseball on the internet since Y2K. Follow him on Twitter.

Howard Cole is a news and sports journalist in Los Angeles. Credits include Sports Illustrated, Forbes, Rolling Stone, LAT, OCR, Guardian, LA Weekly, Westways, VOSD, Prevention, Bakersfield Californian and Jewish Journal. Founding Director, IBWAA.