Wilbur Jackson and John Mitchell Dedication About More Than History

In this story:

TUSCALOOSA, Ala. — He couldn’t talk at first, and that was before the plaque had been unveiled.

When the words finally started to come out, they more than reflected the emotions that John Mitchell had been feeling all weekend. He was trying not to be overwhelmed.

“From the bottom of my heart, I can’t tell you what this means to me,” he finally got out to the dignitaries, media and fans who had gathered to watch history.

He didn’t have to. Everyone got it.

Saturday afternoon, before the Alabama football team participated in the final scrimmage of spring practices, something much more important happened out in front of Bryant-Denny Stadium.

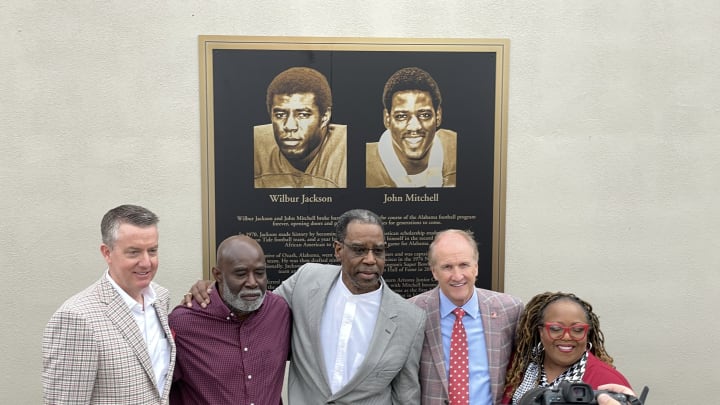

As part of a weekend celebration, the university unveiled a large plaque honoring Wilbur Jackson and Mitchell or helping break down racial barriers not only with the Alabama football program approximately 50 years ago, but the Southeastern Conference and in sports as a whole.

It was also the next important milestone in Alabama athletics recognizing these types of achievements.

In 2020, Nick Saban helped lead a march of hundreds of athletes, coaches and staff to protest racial injustice in the United State. The Black Lives Matter rally symbolically ended at Foster Auditorium, where the Stand at the Schoolhouse Door occurred in 1963.

Also, in 2020, Wendell Hudson, the first Black athlete to accept a scholarship to Alabama, had his basketball jersey retired at Coleman Coliseum, right before most of sports shut down due to the onset of the coronavirus pandemic.

“It’s great,” was Hudson’s reaction to Saturday’s ceremony.

In terms of pioneers, one would be hard-pressed to find a bigger one in Alabama football history than Jackson, the first Black athlete to sign a football scholarship to play for the Crimson Tide.

Integration was a hot issue in the South in the 1960s, especially in Alabama, which had endured everything from the bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, which killed four young girls, to Governor George Wallace trying to block the University of Alabama’s first two Black students from entering their classrooms.

Tensions were at an all-time high, and for years Coach Paul W. “Bear” Bryant maintained that the local social and political climate wasn’t ready for Black football players. During a deposition for an anti-discrimination lawsuit filed against the school, Bryant testified that he had actively been trying to recruit Black players for years, but had found no takers, while forwarding some to other coaches.

Alabama finally made history with Jackson, but the first Black player to get into a game was Mitchell, a two-time Junior College All-American defensive end at Eastern Arizona Junior College who Bryant nearly missed out on.

Mitchell was already committed Southern California when Bryant attended coaching clinic with John McKay, and the Trojans couch couldn’t help but brag about a player he had snared from Mobile. Bryant quickly excused himself from the room and called his recruiter on the Gulf Coast, and told him to look up every John Mitchell Sr. in the phone book until they found his father.

Mitchell went on to be named an All-American in 1972, the first Black co-captain at Alabama, the Tide’s first Black assistant coach, and later became the conference’s first Black defensive coordinator at LSU.

“I’d do it again in a minute,” he said. “If you’re a football player, you dream of playing for Coach Bryant.”

During his junior season, Jackson led the Southeastern Conference by averaging 7.1 yards per carry. For his senior year, he switched from halfback to fullback in the new wishbone offense and accumulated 752 rushing yards on 95 carries for a 7.9 average.

Alabama went 11-1 in 1971, 10-2 the following year and capped it with a 11-0 regular season in 1973 to be named the United Press International national champion in the final year the coaches’ poll was conducted prior to bowl games (it lost to Notre Dame in the Sugar Bowl, 24-23). All three years, the Crimson Tide captured the Southeastern Conference championship.

Jackson was selected in the first round of the 1974 draft by the San Francisco 49ers and played eight years in the National Football League, including with the 1982 Super Bowl champion Washington Redskins. He accumulated 895 yards his rookie season and was named NFC Rookie of the Year, and for his career posted 3,852 career rushing yards on 971 carries, with 1,572 receiving yards on 183 catches.

Mitchell went into coaching, including 24 years with the Pittsburgh Steelers.

“Look at the opportunities that both of those fine men _ and I coached with John Mitchell with the Cleveland Browns so I know him really, really well,” Saban said. “He's a great human being and a great man. So is Wilbur.”

Nevertheless, they opened an important door at Alabama, not only for the players who immediately came behind them like Sylvester Croom (by the 1973 season, one-third of Alabama’s starters were Black) and Ozzie Newsome, but players who have excelled under Saban, like Heisman Trophy winners Mark Ingram II, Derrick Henry, DeVonta Smith and last year Bryce Young.

How different things may have been had they not.

“It wasn’t about having a burden to carry across those who came behind us, it was just to do your best, to be the best that I could be every day,” Jackson said. “That was hard. That was hard enough to go to practice every day. To carry the burden beyond that would have been unbearable.”

Yes, what they experienced was very much like what so many players have over the years.

For example, Mitchell told the story again about how when he was helping recruit Newsome. Bryant told him “Don’t let him out of your sight.” He took it literally, sleeping on the family’s couch until the future Hall of Fame tight committed to the Crimson Tide.

Jackson, who originally hailed from Ozark, Alabama, was pushed to the brink of quitting, but needed one more dollar for the fare home. The low-key standout didn’t want to ask any teammates for it because he knew they would want to know what it was for.

The next day went a little better and he changed his mind.

“If I had one more dollar, I might have left,” Jackson said, thankful that he never had enough for the ticket.

Now their likeness is out in front of the most celebrated place on campus.

On the other side of the entrance to Bryant-Denny Stadium is the statue of two players holding a Crimson Tide flag. They’re supposed to be anonymous, but were modeled by former center Antoine Caldwell, and middle linebacker Matt Collins. That means that three of the faces on permanent display looking out over what’s known as the Walk of Champions are former Black athletes.

“It was very touching,” Mitchell said. “It’s a day that I’ll never forget.”

Christopher Walsh is the founder and publisher of Alabama Crimson Tide On SI, which first published as BamaCentral in 2018, and is also the publisher of the Boston College, Missouri and Vanderbilt sites. He's covered the Crimson Tide since 2004 and is the author of 26 books including “100 Things Crimson Tide Fans Should Know and Do Before They Die” and “Nick Saban vs. College Football.” He's an eight-time honoree of Football Writers Association of America awards and three-time winner of the Herby Kirby Memorial Award, the Alabama Sports Writers Association’s highest writing honor for story of the year. In 2022, he was named one of the 50 Legends of the ASWA. Previous beats include the Green Bay Packers, Arizona Cardinals and Tampa Bay Buccaneers, along with Major League Baseball’s Arizona Diamondbacks. Originally from Minnesota and a graduate of the University of New Hampshire, he currently resides in Tuscaloosa.

Follow BamaCentral