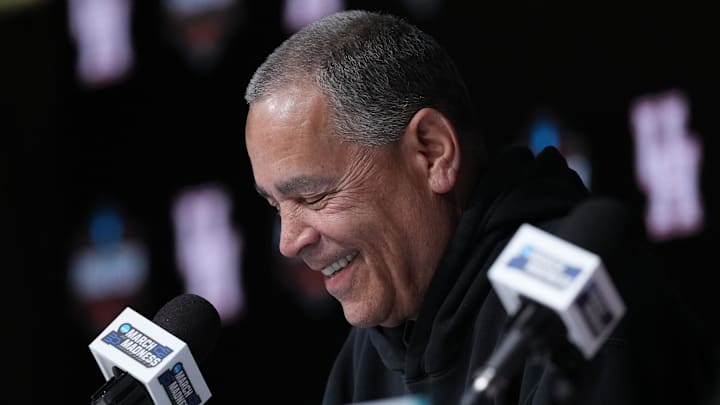

On the Doorstep of a National Championship, Kelvin Sampson Can Finally 'Smell the Roses'

In this story:

At 69 years old, Kelvin Sampson is still having a hard time taking stock and living in the moment.

When he got back to the team hotel in San Antonio on Saturday night after Sampson’s Houston Cougars knocked off Duke with a dramatic, even historic comeback in the Final Four, a legion of UH fans waited to greet him with raucous cheers and warm gratitude.

Sampson’s nature, however, was to be solely focused on the next task ahead — Monday night’s showdown with Florida for the national championship — and while he certainly appreciated all the well-wishers, he admitted Sunday that he wasn’t exactly in his element.

“I don't know. I'm not very good at that stuff,” Sampson said at Sunday’s off-day press conference. “ ... Certainly something to savor and enjoy. It's indicative of our journey, our success.

“My mind was focused on getting Kellen (Sampson, his son and top assistant coach) by himself and getting to a laptop and looking at Florida. I'm not very good at that.

“My mother always used to tell me that I had to learn to smell the roses. My mother passed away in 2014. I never did learn.”

Oklahoma fans no doubt have a soft spot in their heart for the coach who guided their Sooners for 12 seasons from 1994-2006 and won more than 72 percent of his games (280-108) with 11 NCAA Tournament berths, three Sweet Sixteens, two Elite Eights and one Final Four.

“Kelvin Ball” was maybe not as aesthetically pleasing as his predecessor’s “Billy Ball,” but it was every bit as successful. Billy Tubbs led the Sooners for 14 seasons, won 71.6 percent of his games and tallied a 333-132 record with 11 NCAA Tournaments, five Sweet Sixteens, two Elite Eights, and a Final Four trip that led to a loss in the national championship game.

Now, going on almost 20 years since Sampson roamed the Sooner sidelines (famously and frequently in a denim shirt that illustrated his blue-collar culture), he’s reached the pinnacle of his profession, his first national championship game.

If he wins one more game, he’ll hit the 800-win milestone. If he wins one more game, he’ll be the oldest coach to ever win a national title, surpassing UConn’s Jim Calhoun (68).

What does all that mean to Sampson?

“It's probably a good question,” he said. “When you're pressing 70, you look at things a lot differently. I mean, you're grown up now. You're 70. I've spent a little time this morning with my grandkids. First time I went to the Final Four in 2002, my son (Kellen) was on the team, or he was on the bench with us.”

Now Kellen is his right hand man.

“Over the years, things kind of come full circle in some ways,” Sampson said. “Last night I got so many texts. I haven't returned any. There's too many to even look at. I didn't even get through all of them.”

Among those who texted Sampson were college legends like Tubby Smith, Rick Barnes and Tom Izzo, and arguably the NBA’s greatest coach ever, Gregg Popovich.

“A bunch of the older coaches,” he said. “They all kind of had similar messages to me: win one for the old guys, something like that. We were all young at the same time coming up.”

In 11 seasons at Houston, Sampson has won 299 games and lost 83, a winning percentage of 78.3. Sampson has reinvented himself with the Cougars since his exile from the game following two successful but not necessarily NCAA-compliant seasons at Indiana. He spent six seasons as an assistant in the NBA with Milwaukee and Houston, and now has elevated the Cougars to heights not seen since Phi Slamma Jamma.

In each of the last seven full seasons, Sampson’s squads have made seven straight NCAA Tournaments, six Sweet Sixteens, three Elite Eights, two Final Fours and now the program’s first national championship game since 1984.

Now 36 years into a career that began as a graduate assistant at Michigan State under Jud Heathcote, Sampson — alongside his assistant coach son, Kellen, his basketball ops director daughter, Lauren, and as always with his wife and biggest supporter, Karen — is on the verge of the ultimate basketball achievement.

“It's hard for me to think about the journey without thinking of my mother and father,” he said. “My mother was a nurse. She worked 12-hour shifts. Her shift was either 8 to 8 or 7 to 7. My dad (Ned) was a high school basketball coach in a little country community at Magnolia High School. I'm not even sure if I would know how to get to that.”

Growing up in Pembroke, NC, as a member of the Lumbee Indian Nation, Sampson’s journey has included plenty of trials and triumphs.

But there was always basketball, and there was always home.

“I have a lot of friends back there,” he said. “Some of them are actually here right now. I haven't seen 'em; my wife, Karen, she does a good job of running interference on stuff like that. But coming from a small town where you had to kind of outwork everybody was perfect for me because I didn't get to be an assistant coach for somebody and learn as much as some of these other guys do.”

Even today, Sampson often speaks of the hardpan lessons he learned from his dad and from Heathcote before becoming a head coach at Montana Tech just one year after leaving East Lansing. After two more years as an assistant at Washington State, Sampson took over the Cougars — the Washington State Cougars — and, other than six years in the NBA, has called his own shots ever since.

“Those guys were just old school, discipline, do things the right way, coach 'em up, and play ball,” he said. “That's kind of what I was raised with.”

That’s why the Houston Cougars have been successful over the last decade, and it’s why they were able to overcome a 14-point deficit in the final minutes to get their coach back to the cusp of hoops immortality.

There’s a reason why Sampson’s backcourt from OU’s 2002 Final Four run — Quannas White and Hollis Price — have stayed by his side during most of his run at UH. Like all of his former players, they love him.

Houston’s J’Wan Roberts expressed the same sentiments on Sunday in the Alamo City.

“I mean, too much to say,” he said. “ … For these six years that I've known Coach Sampson, I can honestly say he's like a second father to me, especially on and off the court. He makes sure I'm good, randomly calls me, randomly texts me, tells me he loves me.

“When you come across people like that, you have to keep them with you for a long time. I feel like in the next 5-10 years, Coach Sampson is going to be a person I can call. Hopefully in the future when I have my kids, we can all sit down and have a great conversation about what we've been through.”

Those, then, are the moments that Sampson can embrace. He pauses more these days — he cried a lot in 2023 when cancer stole Sooners icon Ryan Minor, and he took a brief emotional break more than once on Sunday as he talks about family — but age and time has given him the wisdom and the grace to finally be able to reflect and appreciate.

Not necessarily the adoration and applause from the thousands of Houston fans in San Antonio this weekend. But certainly the more intimate interactions with family, old friends, and of course his players.

“I used to come to the tournament when I was a young coach,” Sampson said. “I would sit in those stands and look at the two coaches in the championship game. You think you'd like to be there one day, if you could ever get a chance.

So for me, it's a lot of gratitude, a lot of appreciation for having this opportunity.

“But you owe it to so many people. You don't do things like this in a vacuum. I got a great team, a great staff. I'm able to work independent of everything. I run the program without any resistance. I make all the decisions. I do everything on my own, so — with my staff, of course. We've kind of done it our way. It's worked out pretty good.”

John is an award-winning journalist whose work spans five decades in Oklahoma, with multiple state, regional and national awards as a sportswriter at various newspapers. During his newspaper career, John covered the Dallas Cowboys, the Kansas City Chiefs, the Oklahoma Sooners, the Oklahoma State Cowboys, the Arkansas Razorbacks and much more. In 2016, John changed careers, migrating into radio and launching a YouTube channel, and has built a successful independent media company, DanCam Media. From there, John has written under the banners of Sporting News, Sports Illustrated, Fan Nation and a handful of local and national magazines while hosting daily sports talk radio shows in Oklahoma City, Tulsa and statewide. John has also spoken on Capitol Hill in Oklahoma City in a successful effort to put more certified athletic trainers in Oklahoma public high schools. Among the dozens of awards he has won, John most cherishes his national "Beat Writer of the Year" from the Associated Press Sports Editors, Oklahoma's "Best Sports Column" from the Society of Professional Journalists, and Two "Excellence in Sports Medicine Reporting" Awards from the National Athletic Trainers Association. John holds a bachelor's degree in Mass Communications from East Central University in Ada, OK. Born and raised in North Pole, Alaska, John played football and wrote for the school paper at Ada High School in Ada, OK. He enjoys books, movies and travel, and lives in Broken Arrow, OK, with his wife and two kids.

Follow johnehoover