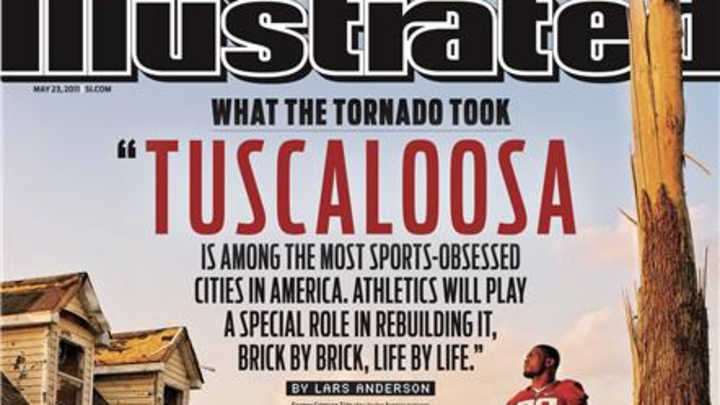

Tuscaloosa Marks Anniversary of 2011 Tornado

Everything changed on April 27, 2011.

It was an unusually warm day in Tuscaloosa, where most University of Alabama students were only dreading their upcoming finals and still basking from the unofficial offseason football holiday known as “A-Day.” Less than two weeks after the annual celebration surrounding the final scrimmage of spring practices, this one had been extra special because it had included Nick Saban having his statue unveiled in front of again-expanded Bryant-Denny Stadium, where the other coaches who have won national championships are permanently honored.

Intense warnings had been issued for that afternoon, but the sun had been out in between the passing storm clusters that have been known to frequent the South on a regular basis this time of the year. A particularly nasty one had come though in the early-morning hours, but still things went on as if it was nothing was out of the ordinary.

That is until about 5 p.m., when a monster tornado emerged in the southwest corner of Tuscaloosa and quickly began a mile-wide path of carnage.

Words simply can’t adequately describe what everyone experienced and endured. This wasn’t something on television or at a far-off place. They witnessed it while looking out of their windows, heard it as it ripped through everything in its way, and felt it as it cut through the heart of the community. Anyone who called Tuscaloosa home knew people who lost their businesses, homes or lives: Their friends, colleagues, and loved ones.

The gash went deeper than any satellite image could show, and after surveying the scene a couple of days later President Barack Obama said “I’ve never seen devastation like this.” To come up with a comparison, one needed to talk with those who had experienced Hurricane Andrew or Katrina, or even a war zone.

That’s what 15th Street and McFarland Boulevard, perhaps the busiest intersection in town, resembled. Nearby, Hokkaido Japanese Steak and Sushi Bar was completely destroyed. The pile of rubble across the street gave no hint to what had been there before, and the path of destruction stretched well beyond what the eye could see.

Standing there one couldn’t help but fear the worst.

“I’m just thanking God that I didn’t get picked up with it,” said linebacker Jerrell Harris, who was in an apartment on 15th Street when it struck. “You never think it’ll happen to you.

“It’s mind-blowing.”

Former Crimson Tide football player Javier Arenas was one of the fortunate ones to emerge uninjured after his house disintegrated around him, but two names in particular gave immediate faces to the disaster: Loryn Brown, the well-known daughter of former Alabama football player Shannon Brown, and Ashley Harrison.

“A special young lady,” former defensive tackle Bob Baumhower, who employed Brown at one of his restaurants, later said. “We went down to the visitation in Wetumpka and it was just amazing the support and the lives that she touched. You talk about making a difference, the short time she was here she made a huge difference.”

Harrison was the girlfriend of long-snapper Carson Tinker, and the two had taken refuge in a closet along with his roommates and their dogs. When the house took a direct hit, Ashley was ripped from his arms as they were thrown. Tinker sustained a broken wrist, concussion and ankle injury, while she died almost immediately from a broken neck. Harrison was 22.

Most people first heard about both by word of mouth, not so much because the power was out in most of Tuscaloosa, but due to the sheer volume of people helping their neighbors dig out or salvage what they could. Stories, mostly uplifting, were passed along as volunteers poured into the obliterated neighborhoods and went door-to-door asking “What do you need?” while passing out whatever supplies they could.

Saban, too, contributed on many levels. Knowing full well that when you’re the head of the Crimson Tide football program being the biggest face of the community comes with the job, he embraced the role. He served as a spokesman during Crimson Caravan gatherings, participated in a telethon, helped set up a storm recovery program through his Nick’s Kids Fund and was in the process of establishing a program to sponsor a specific neighborhood’s recovery.

But just as important as any financial donation, including his wife Terry purchasing hundreds of $50 gift cards and handing them out so people could buy what they needed, may have been visiting a shelter and spending time with people there.

“Sometimes your presence means something and you just have to listen,” he said. “We fed everyone and we gave away a thousand Alabama shirts, which everyone was really excited about. You would have thought we gave everyone an SUV they were so happy to have an Alabama shirt.

“You can watch all this on television and see the devastation, but until you meet the family that lost their home and all their belongings, things that were dear and personal to them, the guy who just lost his business, it was just blown away, but most importantly anyone who lost any loved ones. That’s the saddest thing.”

The coach also encouraged players, current and former, to do what they could as well, although little prompting appeared necessary.

For days, John Fulton, Brandon Gibson, Harrison Jones and Barrett Jones — who spent his previous two spring breaks in Haiti helping with earthquake recovery — were in numerous neighborhoods helping out.

“It’s the same kind of devastation,” Barrett Jones said. “We all want to show we’re part of this community too. We’re all affected by it.”

James Carpenter, Marcell Dareus and Cory Reamer raised money at Crimson Caravan events, with Julio Jones, Mark Ingram and Greg McElroy all coming back to help out. Courtney Upshaw held a special autograph session that led to thousands in donations and also brought supplies.

Arenas drove back to Kansas City, where he played for the NFL’s Chiefs, and did likewise, as did Preston Dial from Mobile. Justin Smiley bought an SUV for a family. DeMeco Ryans, who was supposed to be recovering from a torn Achilles, volunteered and made a sizable donation. Le'Ron McClain organized truckloads of supplies.

“Tuscaloosa may never be the same, and I think people have to realize that, but I also think that you almost have to look forward and as an opportunity to rebuild,” Saban said. “We can all make our community better by what we can all pitch in and do, but it’s not something that’s going to take two weeks, or two months, it’s going to take years.”

It took contributions by people like Baumhower, who helped feed people in Alberta City, which evolved into a relief hub.

“It was an amazing thing to watch,” said Baumhower, who estimated that between 30,000 and 40,000 meals were dished out.

It continued through the hot summer, when linebacker Nico Johnson and some of the other football players including defensive back Nick Perry and tackle D.J. Fluker got a mind-blowing look at what was left of Holt. Even though three months of non-stop cleanup efforts had transformed the remains of a neighborhood into basically a big stretch of open land, the surrounding devastation and corresponding smells of the twisted and broken wreckage remained overwhelming.

But they were not alone while helping out with the rebuilding of two houses. Also lending a hand were a number of volunteers from Saban’s alma mater Kent State, including some of the players they would soon face in the season opener at Bryant-Denny Stadium,

The trip was organized after Kent State athletic director Joel Nielson essentially asked Saban, “What can we do to help?”

“Being from Alabama, I definitely wanted to go,” said Kent State running back Jacquise Terry, the proud product of Phenix City. “I was eager to help.

“I heard through people in Birmingham and Tuscaloosa how bad it was, you know sometimes people can exaggerate, but it was worse than they really explained. It was worse than I thought, I so I was very shocked.”

The first house was completed just in time for the Golden Flashes’ return in September, but each and every day the Crimson Tide woke up to the realities of what had happened, with no end in sight.

Yet with the return of football, the familiar feel of everyday life began to return, and the bright lights from Bryant-Denny Stadium helped fill the voids as the area made the transition from cleanup to rebuilding. Fans had never been more eager to see their beloved Crimson Tide play again, and even though coaches were concerned about there being too much pressure on the players to try and win a national championship for the ravaged community.

They went on and won the next two titles anyway, and were joined by the Crimson Tide gymnastics, women's golf and softball teams. Men's golf joined in a year later with back-to-back crowns.

“We’re going to fight,” Tuscaloosa mayor Walt Maddox said. “We refuse to let April 27th define us. I told this to the President when he came to visit, the real story about Tuscaloosa, Alabama, is going to be its recovery.”

Some of this post originated from "100 Things Crimson tide Fans Should Know & Do Before They Die," published by Triumph Books

Christopher Walsh is the founder and publisher of Alabama Crimson Tide On SI, which first published as BamaCentral in 2018, and is also the publisher of the Boston College, Missouri and Vanderbilt sites . He's covered the Crimson Tide since 2004 and is the author of 27 books including “100 Things Crimson Tide Fans Should Know and Do Before They Die” and “Nick Saban vs. College Football.” He's an eight-time honoree of Football Writers Association of America awards and three-time winner of the Herby Kirby Memorial Award, the Alabama Sports Writers Association’s highest writing honor for story of the year. In 2022, he was named one of the 50 Legends of the ASWA. Previous beats include the Green Bay Packers, Arizona Cardinals and Tampa Bay Buccaneers, along with Major League Baseball’s Arizona Diamondbacks. Originally from Minnesota and a graduate of the University of New Hampshire, he currently resides in Tuscaloosa.

Follow BamaCentral