The King of the Three True Outcomes, Adam Dunn calls it a career

Adam Dunn will never play a postseason game, but if the 34-year-old slugger is indeed making good on his plans to retire, he does so as the all-time Three True Outcomes king — the exemplar of an era of changing baseball, one of which not everybody is so fond.

As first introduced to the public by Baseball Prospectus co-founder Rany Jazayerli, the Three True Outcomes are the home run, the strikeout and the base on balls, the events which "distill the game to its essence, the battle of pitcher against hitter, free from the distractions of the defense, the distortion of foot speed or the corruption of managerial tactics like the bunt and his wicked brother, the hit-and-run," as Jazayerli wrote back in 2000. A decade and a half later, those outcomes have become even more prevalent at the major league level, both on the field — with soaring rising strikeout rates and still-high home run rates, even if they've fallen from their peak — and in analytic circles.

Wait 'Til Next Year: Did A's mortgage their future with deadline deals?

The Three True Outcomes form the foundation of the Fielding Independent Pitching statistic and the FanGraphs version of Wins Above Replacement. On a certain level, they're a Rorschach blot, lazily linked to Moneyball by those who couldn't be bothered to discern Michael Lewis' book's real message about searching for hidden value on a shoestring budget — and by contrast, to the put-it-in-play small-ball style with which this year's Royals knocked Dunn's A's out of the playoffs before he could make an appearance.

With his 462 career home runs (35th all-time), 1,317 walks (40th) and 2,379 strikeouts (third), Dunn produced a TTO event in 49.93 percent of his career plate appearances, the highest rate of any player with at least 4,000 PA, just ahead of Rob Deer, the patron saint of the phenomenon back when Jazayerli and his fellow statheads began tracking it in the late 1990s:

rank | player | Tto% | years | pa | hr | bb | so |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 | Adam Dunn | 49.9 | 2001-14 | 8,328 | 462 | 1,317 | 2,379 |

2 | Rob Deer | 49.1 | 1984-96 | 4,513 | 230 | 575 | 1,409 |

3 | 48.6 | 2007-14 | 4,380 | 224 | 506 | 1,398 | |

4 | Jim Thome | 47.6 | 1991-2012 | 10,313 | 612 | 1,747 | 2,548 |

5 | Mark McGwire | 45.6 | 1986-2001 | 7,660 | 583 | 1,317 | 1,596 |

6 | 45.5 | 2004-14 | 5,666 | 334 | 655 | 1,591 | |

7 | Carlos Pena | 45.5 | 2001-14 | 5,893 | 286 | 817 | 1,577 |

8 | Mickey Tettleton | 43.5 | 1984-97 | 5,745 | 245 | 949 | 1,307 |

9 | Pat Burrell | 42.8 | 2000-11 | 6,520 | 292 | 932 | 1,564 |

10 | Jay Buhner | 42.3 | 1987-2001 | 5,927 | 310 | 792 | 1,406 |

11 | Gorman Thomas | 42.0 | 1973-86 | 5,486 | 268 | 697 | 1,339 |

12 | Danny Tartabull | 40.9 | 1984-97 | 5,842 | 262 | 768 | 1,362 |

13 | Jose Canseco | 40.7 | 1985-2001 | 8,129 | 462 | 906 | 1,942 |

14 | Mickey Mantle | 40.2 | 1951-68 | 9,907 | 536 | 1,733 | 1,710 |

15 | Troy Glaus | 40.1 | 1998-2010 | 6,355 | 320 | 854 | 1,377 |

16 | Dan Uggla | 39.9 | 2006-14 | 5,368 | 233 | 607 | 1,301 |

17 | Reggie Jackson | 39.7 | 1967-87 | 11,418 | 563 | 1,375 | 2,597 |

18 | Darryl Strawberry | 39.6 | 1983-99 | 6,326 | 335 | 816 | 1,352 |

19 | Gene Tenance | 39.5 | 1969-83 | 5,527 | 201 | 984 | 998 |

20 | 39.4 | 2003-13 | 5,258 | 222 | 636 | 1,216 |

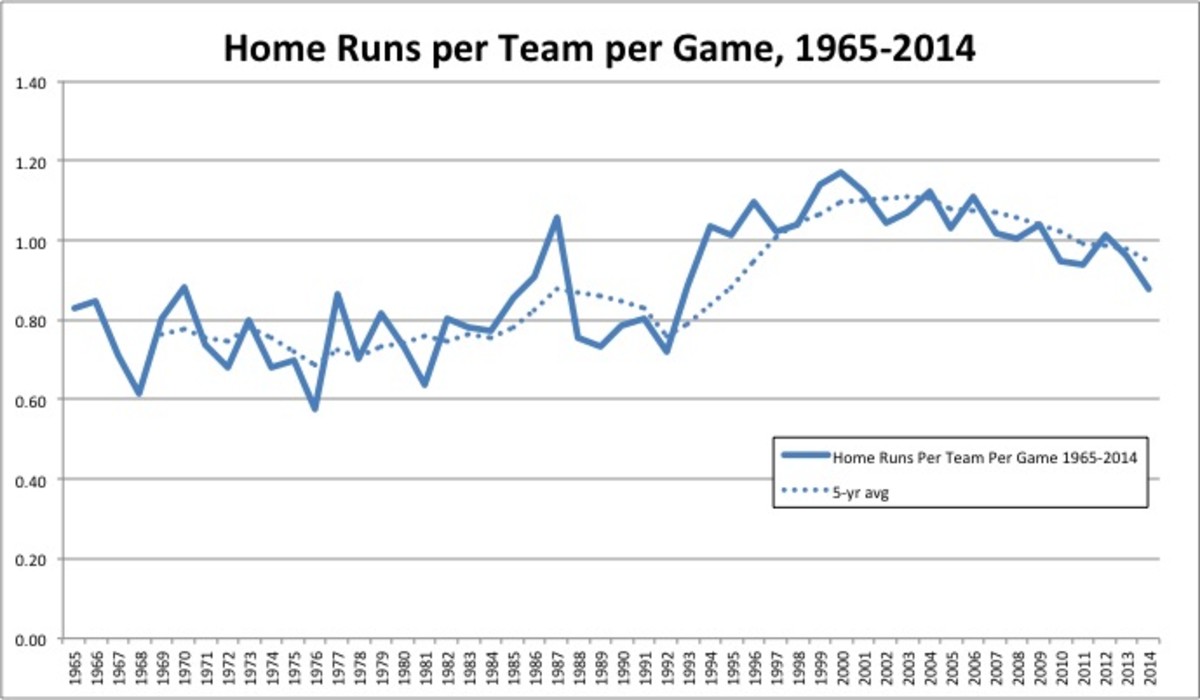

Note that 16 of the 20 players on that leaderboard spent time in the majors after 1993, the period during which home runs have been at their peak:

, namely hitting for power, drawing walks and avoiding double plays.

Consider the history of the single-season strikeout record of 189 as set by Bobby Bonds back in 1970. TTO-types such as Deer (1987), Jose Hernandez (2001) and Preston Wilson (2002) challenged the record, but such was the stigma of holding it that their managers sat them down late in the year to avoid breaking it. Dunn was the man who eventually toppled it in 2004, when he whiffed 195 times, but that mark is now merely tied for 13th as players such as Howard, Reynolds, Chris Davis and Chris Carter surpassed it; Dunn himself did so twice, in 2010 (199) and 2012 (222).

The 19 player-seasons with at least 189 whiffs have been accompanied by an average of 35.4 homers and 2.1 Wins Above Replacement — a slightly above-average performance, more or less, whose value was often suppressed by lousy defense or confinement to a DH role, thus incurring the positional penalty built into WAR. Dunn's 195-K 2004 season produced 46 homers and 4.7 WAR, the third-best among those seasons, with Davis' 199-K, 53-homer 2013 season of 6.1 WAR atop the leaderboard.

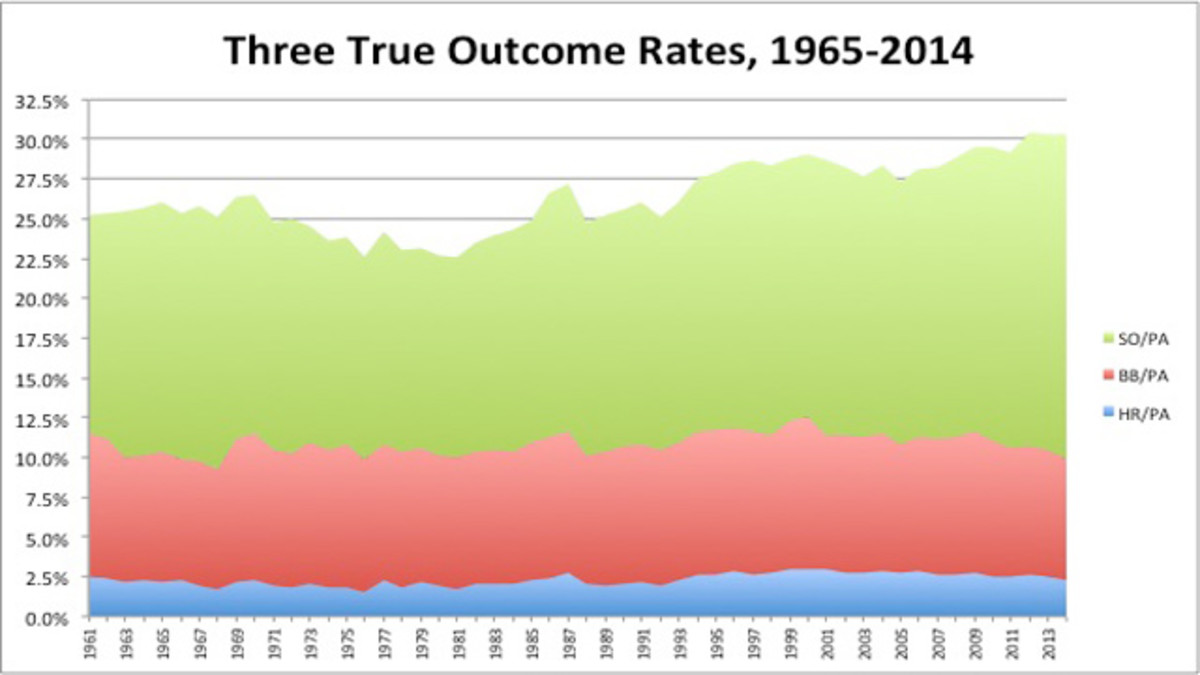

On a league-wide basis, TTO rates have risen to the point that they cumulatively occupy roughly 30 percent of all plate appearances, up from about 25 percent from 1965-1993:

Here's a closer look at the data underlying the last 10 seasons (2005-2014) on that graph:

year | hr% | BB% | so% | TTO5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

2005 | 2.7 | 8.2 | 16.4 | 27.3 |

2006 | 2.9 | 8.4 | 16.8 | 28.1 |

2007 | 2.6 | 8.5 | 17.1 | 28.2 |

2008 | 2.6 | 8.7 | 17.5 | 28.8 |

2009 | 2.7 | 8.9 | 18.0 | 29.5 |

2010 | 2.5 | 8.5 | 18.5 | 29.5 |

2011 | 2.5 | 8.1 | 18.6 | 29.2 |

2012 | 2.7 | 8.0 | 19.8 | 30.4 |

2013 | 2.5 | 7.9 | 19.9 | 30.3 |

2014 | 2.3 | 7.6 | 20.4 | 30.2 |

While some might assume that Dunn's claiming of the TTO crown owed to the combination of his own decline amid the league-wide rising tide of strikeouts, the reality is that he was above 49 percent by the end of the 2006 season, ahead of the pace of Thome (regarded by many as the TTO king for his career length and Hall of Fame-ready performance). Dunn actually finished the 2012 season at 50.03 percent before receding slightly; as it is, he's just six events shy of 50 percent.

It does appear that Dunn's done. In the final year of a four-year, $56 million deal with the White Sox that saw his skills bottom out during an abysmal 2011 (.159/.292/.277 with 11 homers) before recovering, he hit .219/.337/.415 with 22 homers in 511 plate appearances split between the Sox and the Athletics, who traded for him on Aug. 31. With the A’s desperate to fill the power void left not only by the July 31 trade of Yoenis Cespedes but also by the production-sapping injuries of Coco Crisp, John Jaso, Brandon Moss, Derek Norris and Stephen Vogt, Dunn paid an instant dividend when he homered in his first plate appearance for the green-and-gold. But he went just 7-for-42 with one double and no homers from Sept. 11 onward, sitting against left-handed starters in all but one game.

Royals earn overdue postseason win as Athletics complete collapse

Nonetheless, it still rated as a surprise that on Wednesday night, A's manager Bob Melvin kept Dunn on the bench with righty James Shields on the mound; instead, he started Moss at DH, Vogt at first base and Sam Fuld in rightfield. Moss homered twice and Fuld went 2-for-5 with a walk. It was in pinch-hitting for Vogt’s sub, righty Nate Freiman, with switch-hitting Alberto Callaspo against righty Jason Frasor in the 12th inning that would have best suited Dunn. Callaspo made the move pay off by expanding his zone to single in a run for his first RBI since Aug. 24; he had gone 4-for-50 since then.

By not getting into the game, Dunn left intact an unenviable streak of having played 2,001 regular-season games without a single postseason appearance, the highest active total but just the 14th-highest of all time. Hall of Famer Ernie Banks holds the record (2,528 games), and five other Hall of Famers — Luke Appling, Ron Santo, Joe Torre, Harry Heilman and George Sisler — all played in more than Dunn without a taste of playoff action. All six of those players spent at least part of their careers in the pre-division play era (1969 onward) when only the pennant winners got to play in the postseason; the next-highest total from the Wild Card era belongs to Vernon Wells (1,731), while the highest active total now belongs to Alex Rios (1,586).

Dunn's not going to wind up in Cooperstown alongside Banks and company, nor should he. While he reached the 30-homer plateau nine times and the 40-homer plateau six times (including four straight seasons with exactly 40), he never led his league, though he did finish in the top-five seven times and as a runner-up three times. He had eight seasons of at least 100 walks, six with at least 100 RBI, and he was durable enough to play at least 158 games seven times, and at least 149 games in 10 seasons.

Still, horrendous defense (-173 runs, according to Baseball-Reference.com) offset much of his offensive value as he spent his first 11 seasons trapped in the National League, without the benefit of regular DH duty, then struggled to adapt to the role once he signed with the White Sox. For his career, Dunn hit .237/.364/.490 for a 123 OPS+, accumulating 34.2 offensive WAR (based solely on his hitting and baserunning) but a net (including defense and positional adjustments) of just 16.7 WAR.

Looking for a playoff team to root for? Here's who you should pick

At least part of the blame for that imbalance is owed to the general managers above him who spent years sticking a square peg into a round hole instead of trading him to an AL club where he could more fully flourish. Perhaps some of that blame is owed to perceptions of him such as the one espoused by former Blue Jays general manager J.P. Ricciardi, who claimed to have personal insight into Dunn’s soul as well as his style of play. To a radio caller in 2008, Ricciardi said, "Do you know the guy doesn’t really like baseball that much?… Do you know the guy doesn’t have a passion to play the game that much?"

(For the record, it should be noted that neither Ricciardi's Blue Jays [2002-09] nor the Mets who currently employ him in as a special assistant [2011 onward] have gotten even as close to the playoffs as Dunn did when he joined the A's; only as part of Oakland's front office under Billy Beane [2000-01] could Ricciardi take credit for helping a team to the postseason.)

In any case, that Dunn's style of play was polarizing in some circles should be no surprise, for it has been just one front in an ongoing philosophical battle that still rages over the contrast often lazily reduced to "smallball versus Moneyball." Nobody would win with an entire lineup of Dunns, just as nobody is likely to win with an entire team of Jarrod Dysons; even Whitey Herzog's 1980s Cardinals had Jack Clark to knock the ball over the wall once in awhile.

It's not Dunn's fault that he became such a flashpoint. He was very good at some things, and not very good at others, some of which mattered — but which could have been worked around — and some of which did not. It still takes a pretty great hitter to do what he did for as long as he did, and he should be remembered for that.