Pressure growing on Cubs after missing chance to close out Giants in NLDS

LOS ANGELES—Now the screw turns a little tighter. The Cubs have played baseball for seven months from out front and with the wind at their backs. They were in first place for every day of the season but one, way back when their record was an embryonic 4–1. They held a double-digit lead in the NL Central every day starting Aug. 7. They played virtual scrimmage games for the past three weeks. Their season was the baseball version of a Harlem Globetrotters tour: entertaining, but with the outcome never in doubt.

Mind you, today they still lead their Division Series over San Francisco, 2–1. But by letting Game 3 slip away into the dark night, Chicago's joyride has been curbed. Pressure has arrived in earnest.

Most every great team reaches one of these tests. In 1998, the 114-win Yankees trailed Cleveland by the same margin in the ALCS, but then won Games 4 and 5 on the road and didn't lose again that postseason en route to their 24th World Series championship.

The Cubs' plight isn’t nearly so onerous. But they come to AT&T Park today knowing that they had champagne chilled and ready. Holding a 3–2 lead in the eighth, they were five outs away from the NLCS with the ball in the hands of the recently-acquired closer who was supposed to be the last piece of their championship puzzle.

• SI VAULT: Five Outs Away, by Tom Verducci (10.11.2004)

Aroldis Chapman is the hardest throwing human on the planet. He had obtained six outs 14 times in his career. It was the right time and the place to call on him. He was needed because lefthander Travis Wood (single) and righty Hector Rondon (walk) failed to win favorable platoon matchups. Chapman struck out Hunter Pence with his triple-digit heat.

Next up was Conor Gillaspie, who has quickly placed himself with the likes of Pat Burrell, Aubrey Huff, Travis Ishikawa, Cody Ross, Marco Scutaro and the other lost journeyman who came to San Francisco as if it were Lourdes. Chapman had faced 380 lefthanded batters in his career without ever giving up a triple.

Gillapsie, of course, hit a triple. He put the Giants ahead, 4–3, then scored on a single by Brandon Crawford to make it 5–3. Yes, Kris Bryant hit a two-run home run off the roof of a cartoon car advertisement in leftfield to send the game into extra innings. But San Francisco prevailed, 6–5, when Crawford and Joe Panik laced two-base hits in the 13th inning.

The Giants are now 10–0 under manager Bruce Bochy when facing elimination, a definitive statistic that reads like a collective EKG of this team. There is something special that beats within this group. The Cubs have been playing National League ball for 127 years and have never won that many postseason games with their season on the line; the franchise now is 6–15 in elimination games.

More telling of the moment, Chicago now is 5–9 with a chance to clinch. And should the Cubs lose today, the baggage they take home will weigh so much greater than what they took with them to San Francisco.

It’s their biggest test yet. How do they bounce back on Wednesday, knowing the anxiety that would chill the air at Wrigley Field for a Game 5 like a bitter winter wind from Lake Michigan? Game 3 was a loss that corrodes like rust until the remedy of victory is applied. Given the Cubs' talent and panache, they should be fine, but this is new ground and these are the unbreakable Giants.

And then there is this: the Cubs have been playing baseball at Wrigley Field for 101 seasons. They have played only two winner-take-all games in the little green antique jewelry box. They have lost them both.

The Cubs lost Game 7 of the 1945 World Series to Detroit, 9–3, after being down 5–0 before they even came to bat. And they lost Game 7 of the 2003 NLCS, 9–6, after taking a 5–3 lead into the fifth inning. That Game 7 was made possible by the signature game of Chicago’s 108-year wait for a championship, the Bartman Game. That was another night, just like Monday night in San Francisco, when the Cubs were five outs away from moving on.

Big Papi bids Boston adieu: Behind the scenes of David Ortiz's final game

2. Cleveland Rocks

The post-mortems will be overwrought in Boston, as the hyper-dissection of three games out of 165 played will somehow tell the story about what’s “wrong” with the Red Sox. Easy there. The Sox put themselves in a bad position by faltering down the stretch (1–7), costing themselves home field advantage.

This was a team that led the league in runs, and eight of their top 13 position players remain on the good side of 30 years old. If there’s one concern, it would be David Price. The 31-year-old lefty with the contract worth an average of $31 million annually provided Boston with the workhorse starter it needed, but he was never easier to hit (.258/.301/.420; all career full-season worsts), he may be better suited for the NL (he went 10–8 with a 4.28 ERA against winning teams and 7–1, 3.40 against losers) and he has been both bad and unfortunate in the postseason (his teams are 0–9 when he starts). Red Sox advisor Bill James likes to speak of a “transition tax” when big free agents come to Boston, and Price became another example in year one of his seven-year, $217 million contract.

Here’s what happened to the Red Sox in the ALDS: Cleveland. The Indians simply outplayed Boston, perhaps benefiting from the comfort of a false underdog role. Baseball observers started doubting Cleveland because of injuries to starting pitchers Danny Salazar and Carlos Carrasco. But as I wrote earlier last month, we have to stop looking at postseason baseball through the lens of 1968.

Indians answer doubters with sweep of Red Sox to advance to ALCS

The inventory of pitchers with pure stuff keeps growing. One strikeout pitcher after another comes out of bullpens on a nightly basis. The offensive war plan from a decade ago—"Get the starter’s pitch count up and get into the bullpen"—is as outdated as muskets and cannonballs.

This has been the postseason when managers finally figured out how to deploy all these weapons. It’s been the postseason of quick hooks and five-out saves. Did you see Washington manager Dusty Baker grab NLDS Game 3 by the throat Monday? Baker once could have been the poster manager for the old school “ride the starter” mentality. But there he was yanking a veteran starter, Gio Gonzalez, after just two times around the lineup with the bases empty and a 4–3 lead in the fifth, just two outs away from qualifying for a win. It was the right move, and not just because the Nationals went on to win, 8–3.

Cleveland manager Terry Francona managed a terrific series with modern thinking. He inserted his best arm, Andrew Miller, into games in the fifth and sixth innings—more times than Miller had been used that early in his previous 195 appearances (once). Miller faced 16 Boston batters and whiffed seven of them.

Overall, Cleveland’s relievers took care of 38% of the outs in the series and pitched to a 1.74 ERA. They struck out 14 batters in 10 1/3 innings.

Just remember this when you’re watching postseason baseball: The teams that had the top bullpen ERAs in baseball this year were:

1. Nationals: 3.35

1. Dodgers: 3.35

3. Orioles: 3.40

4. Royals: 3.41

5. Indians: 3.45

All but Kansas City reached the playoffs this year. And the best bullpens can be even more effective in the postseason because of the extra off days that allow a manager to use his best relievers longer and more often.

So when you sit down the analyze the ALCS between Toronto and Cleveland, and you can’t help but be impressed by all that righthanded-hitting power on the Blue Jays, remind yourself that bullpens have never been more important in the postseason than they are this year. And the Indians have the better bullpen.

Longest World Series Championship Droughts

Cleveland Indians last won in 1948

Pictured: Bob Lemon

Texas Rangers/Washington Senators never won, Est. 1961

Pictured: Joe Hicks

Houston Astros/Colt .45's never won, Est. 1962

Pictured: Norm Larker

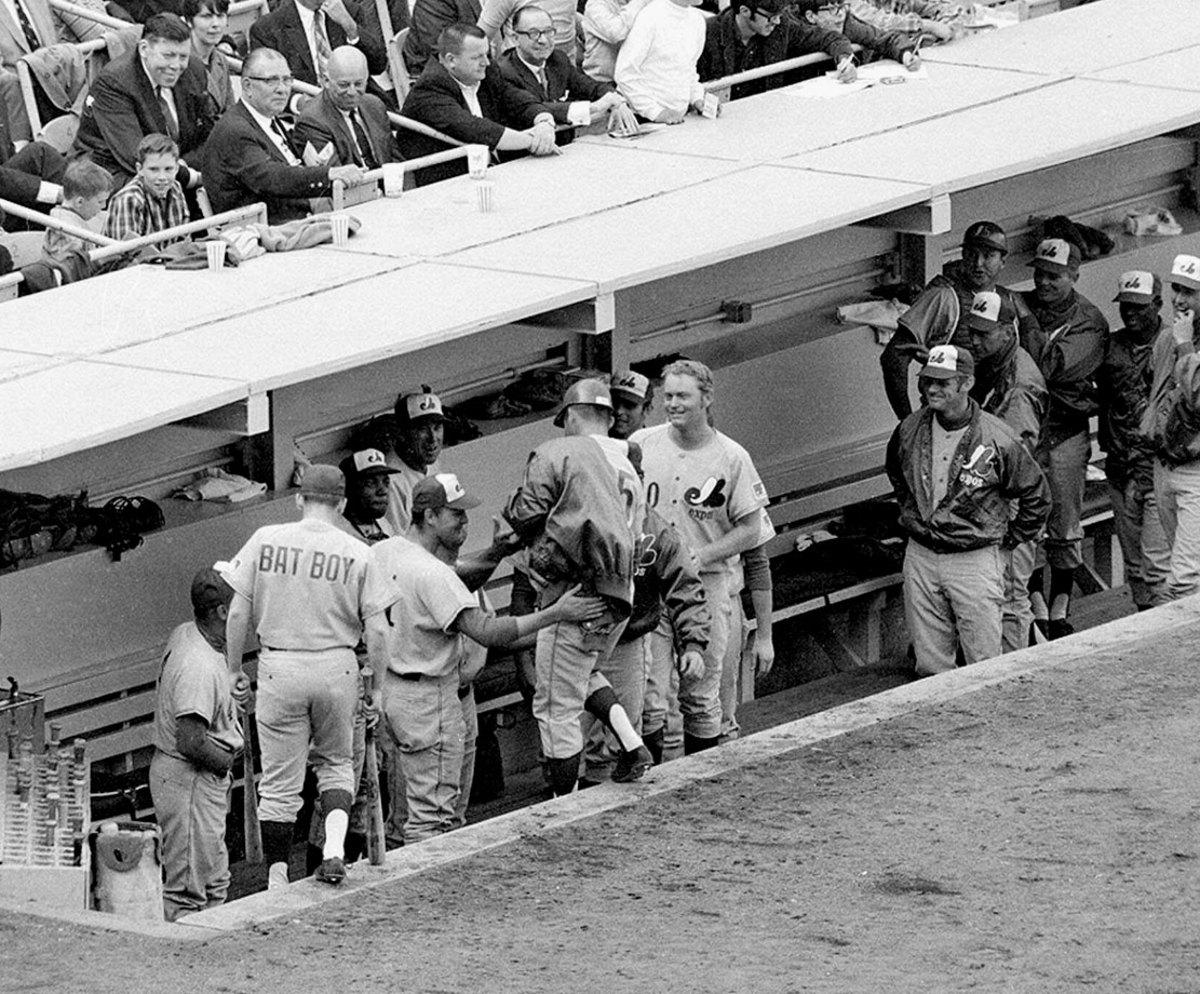

Washington Nationals/Montreal Expos never won, Est. 1969

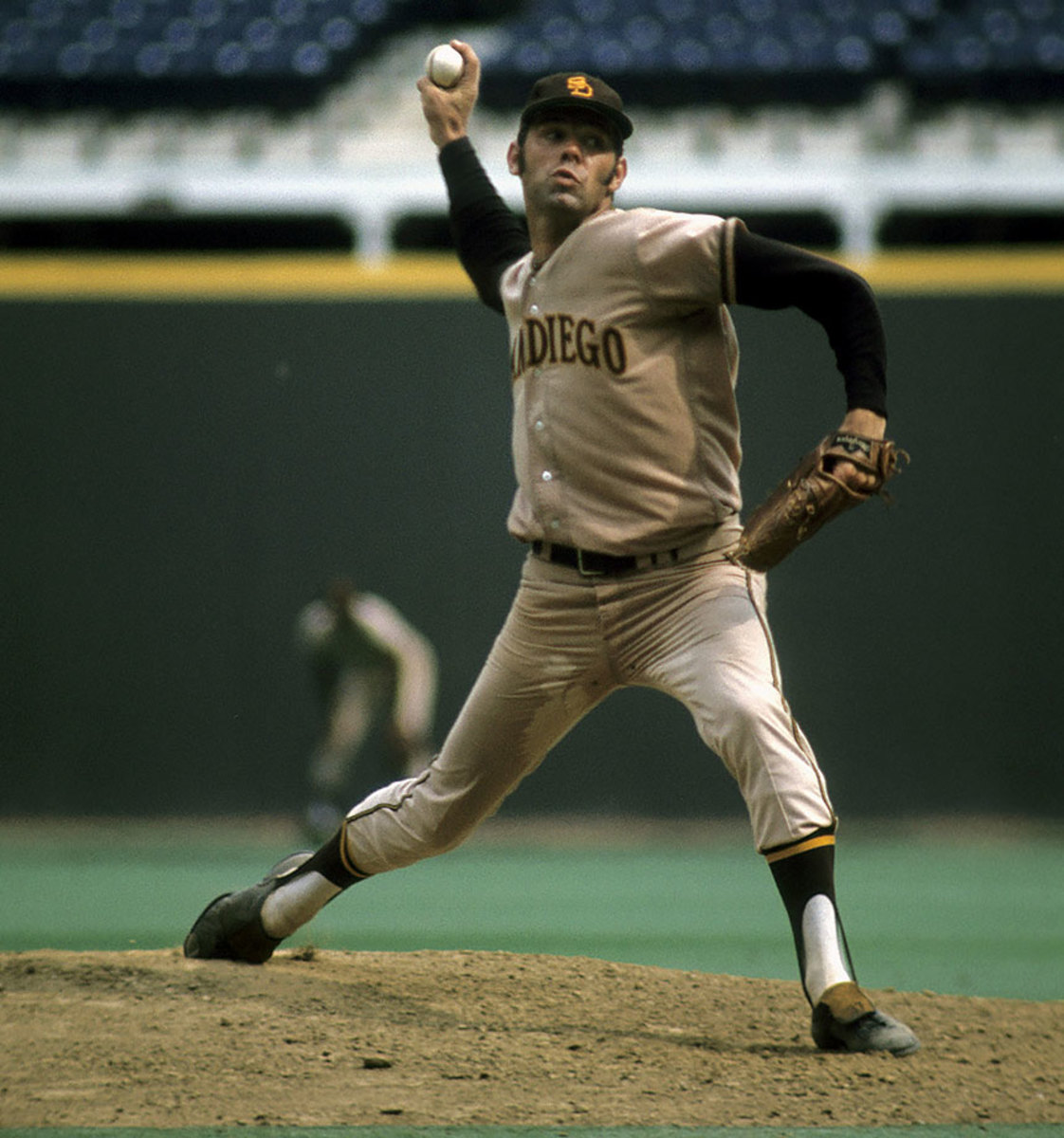

San Diego Padres never won, Est. 1969

Pictured: Clay Kirby

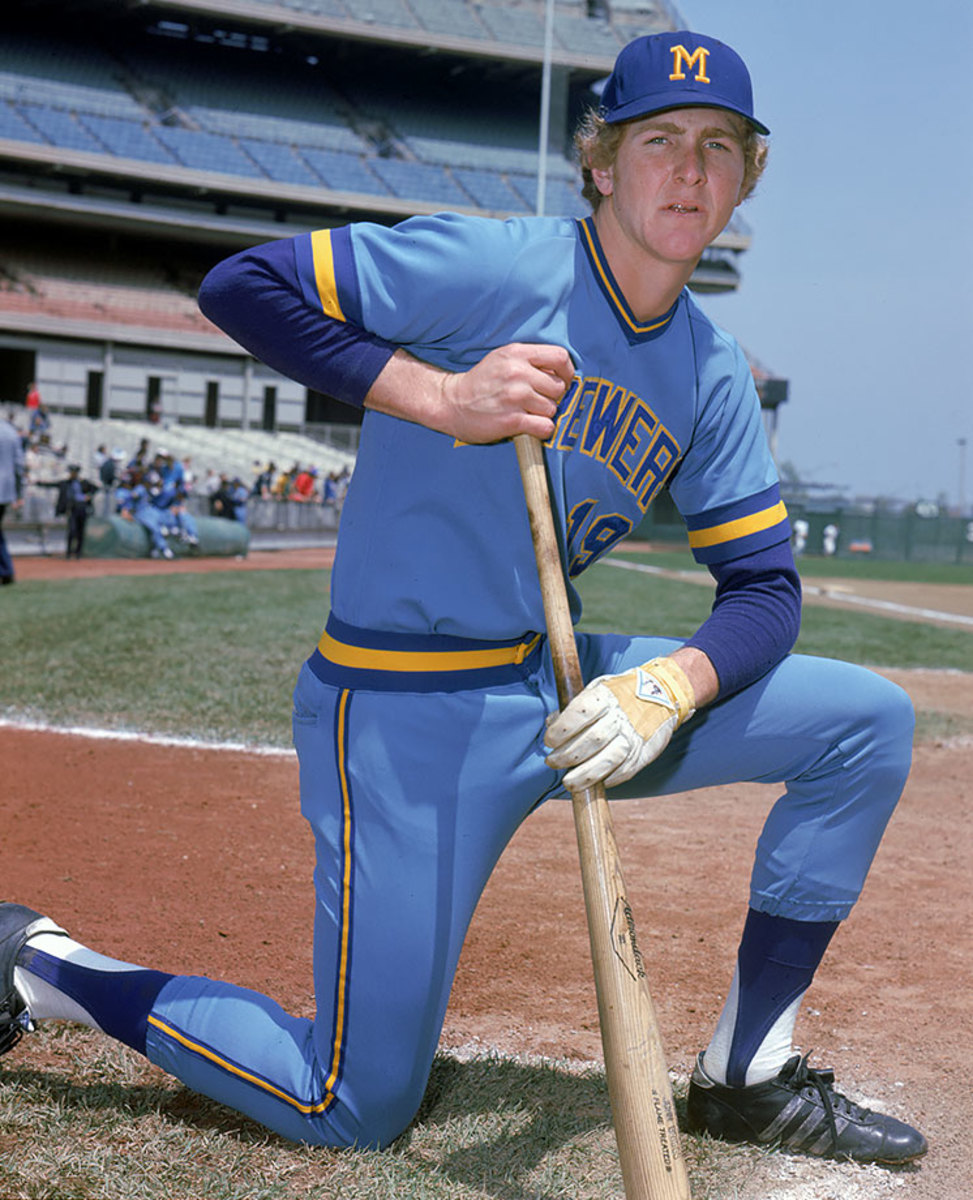

Milwaukee Brewers/Seattle Pilots never won, Est. 1969

Pictured: Robin Yount

Seattle Mariners never won, Est. 1977

Pictured: Part-owner Danny Kaye

Pittsburgh Pirates last won in 1979

Pictured: Willie Stargell and Manny Sanguillen

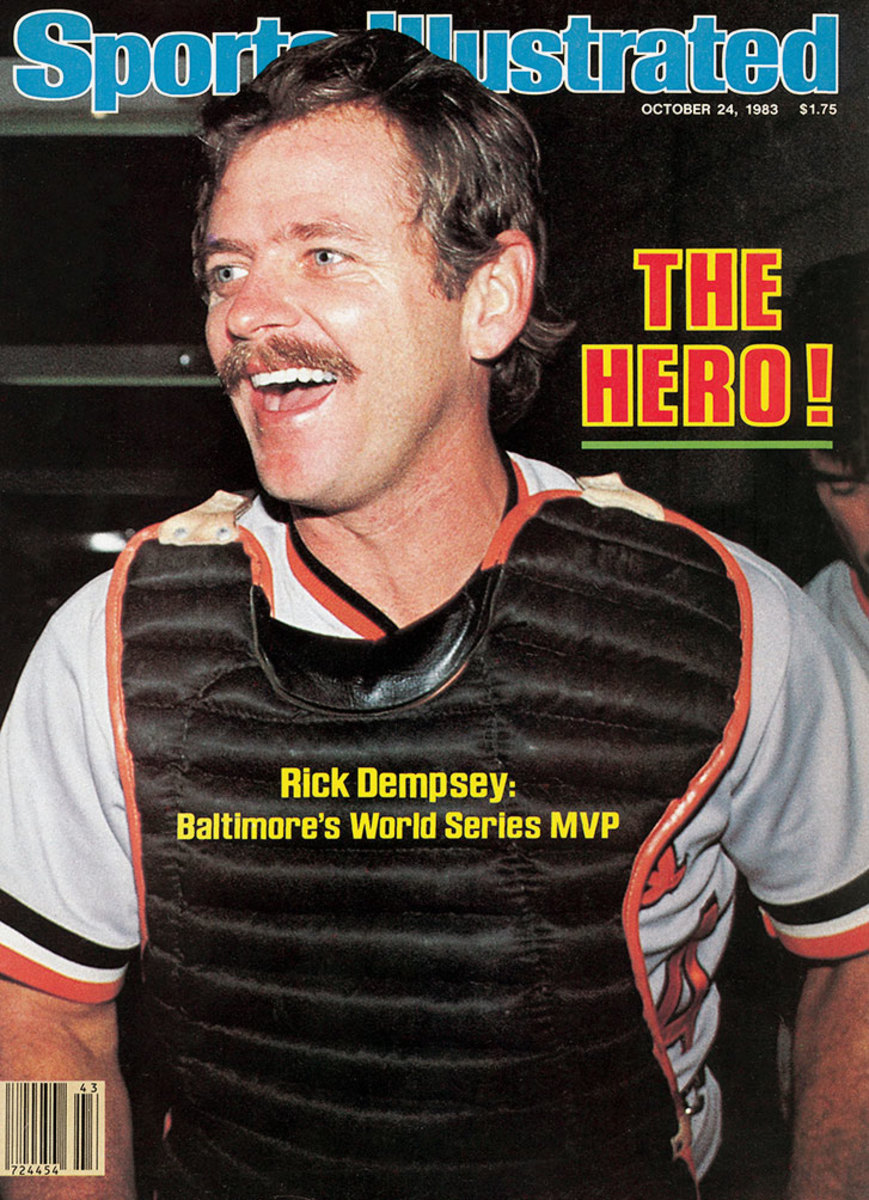

Baltimore Orioles last won in 1983

Pictured: Rick Dempsey

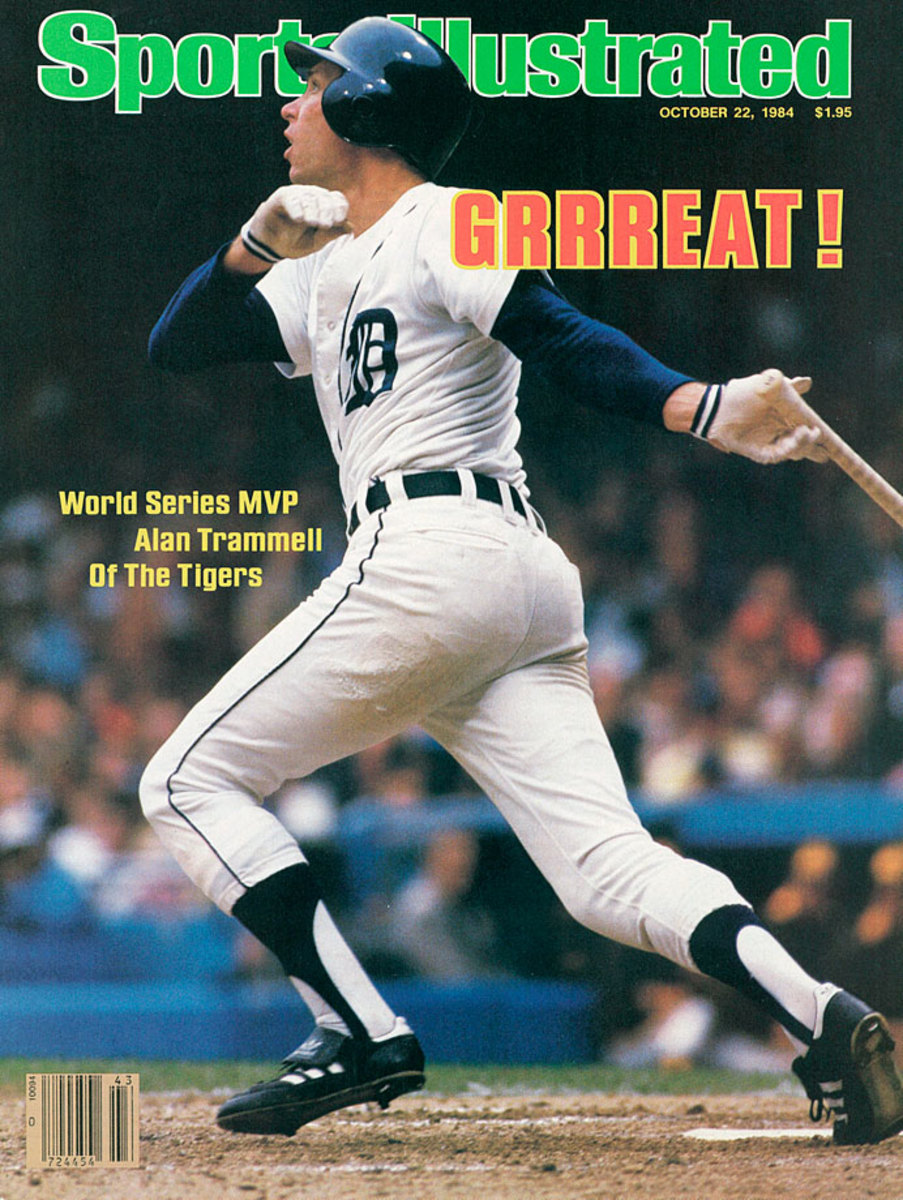

Detroit Tigers last won in 1984

Pictured: Alan Trammell

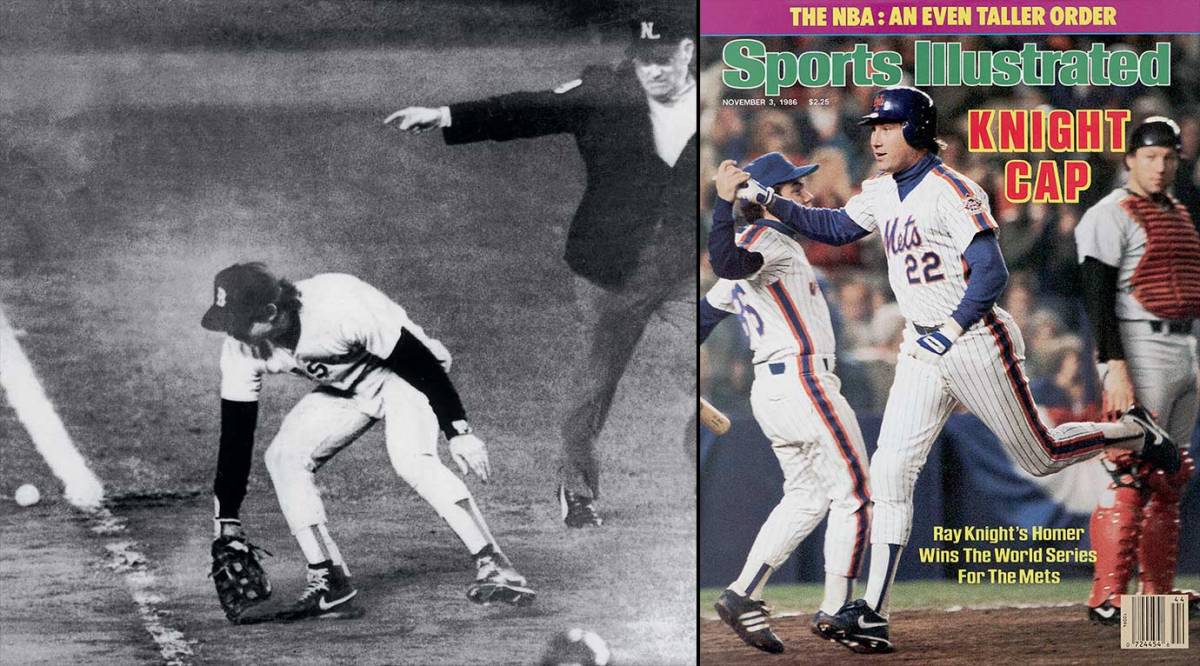

New York Mets last won in 1986

Pictured: Bill Buckner and Ray Knight

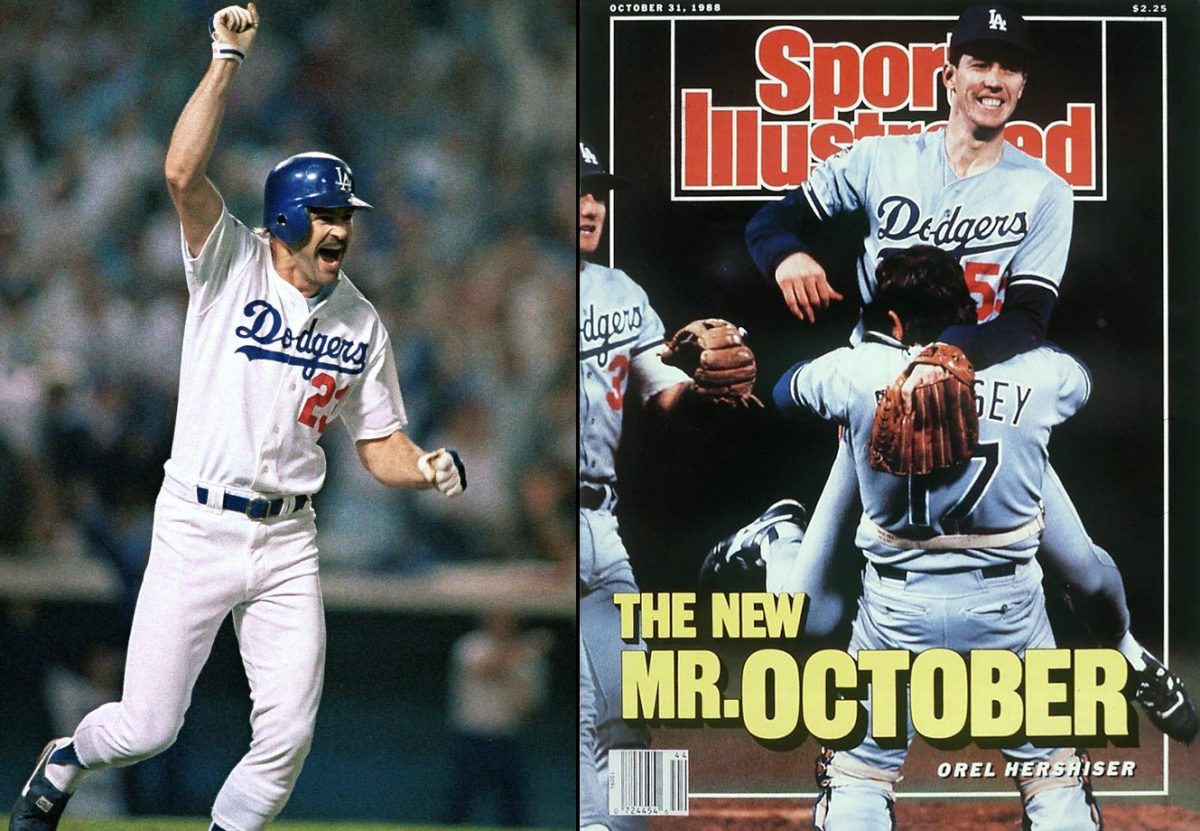

Los Angeles Dodgers last won in 1988

Pictured: Kirk Gibson and Orel Hershiser

Oakland Athletics last won in 1989

Pictured: Dennis Eckersley and Stan Javier

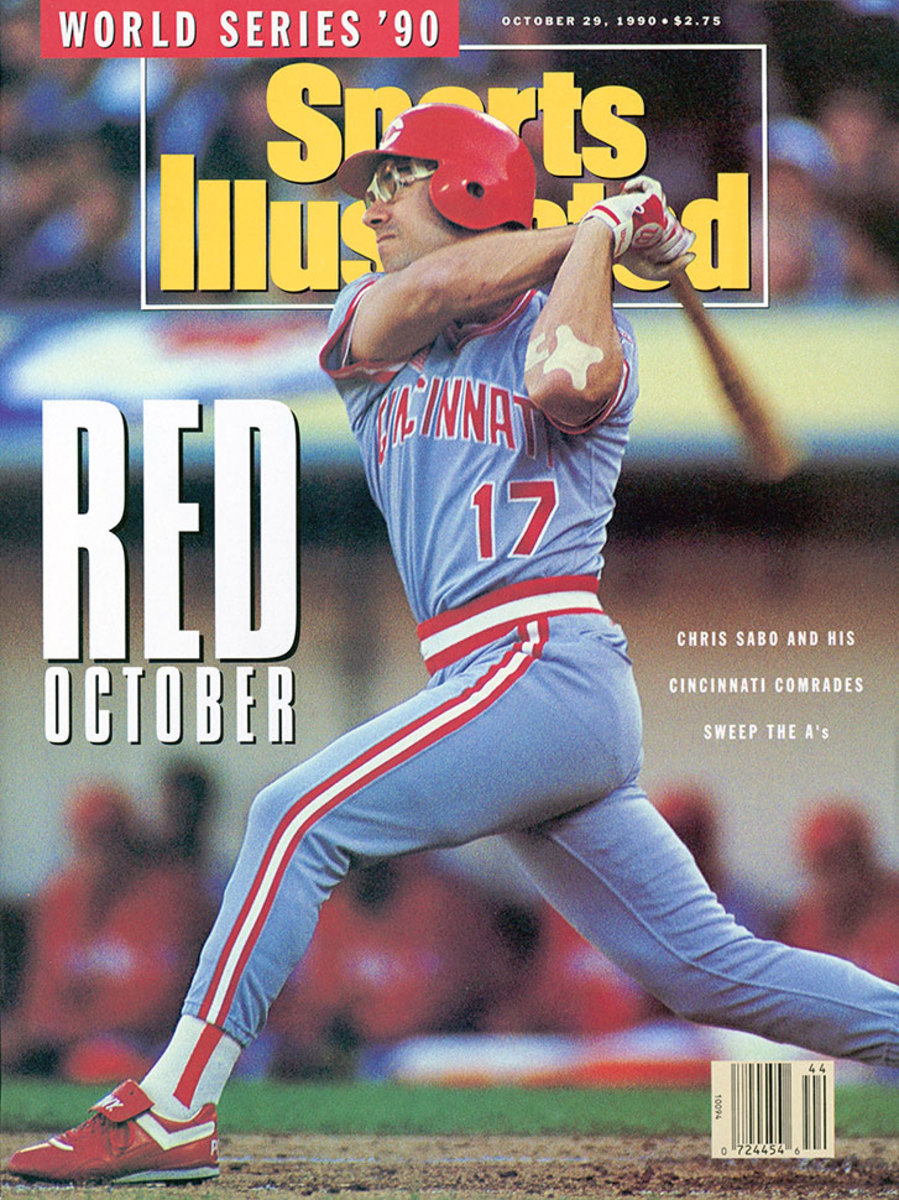

Cincinnati Reds last won in 1990

Pictured: Chris Sabo

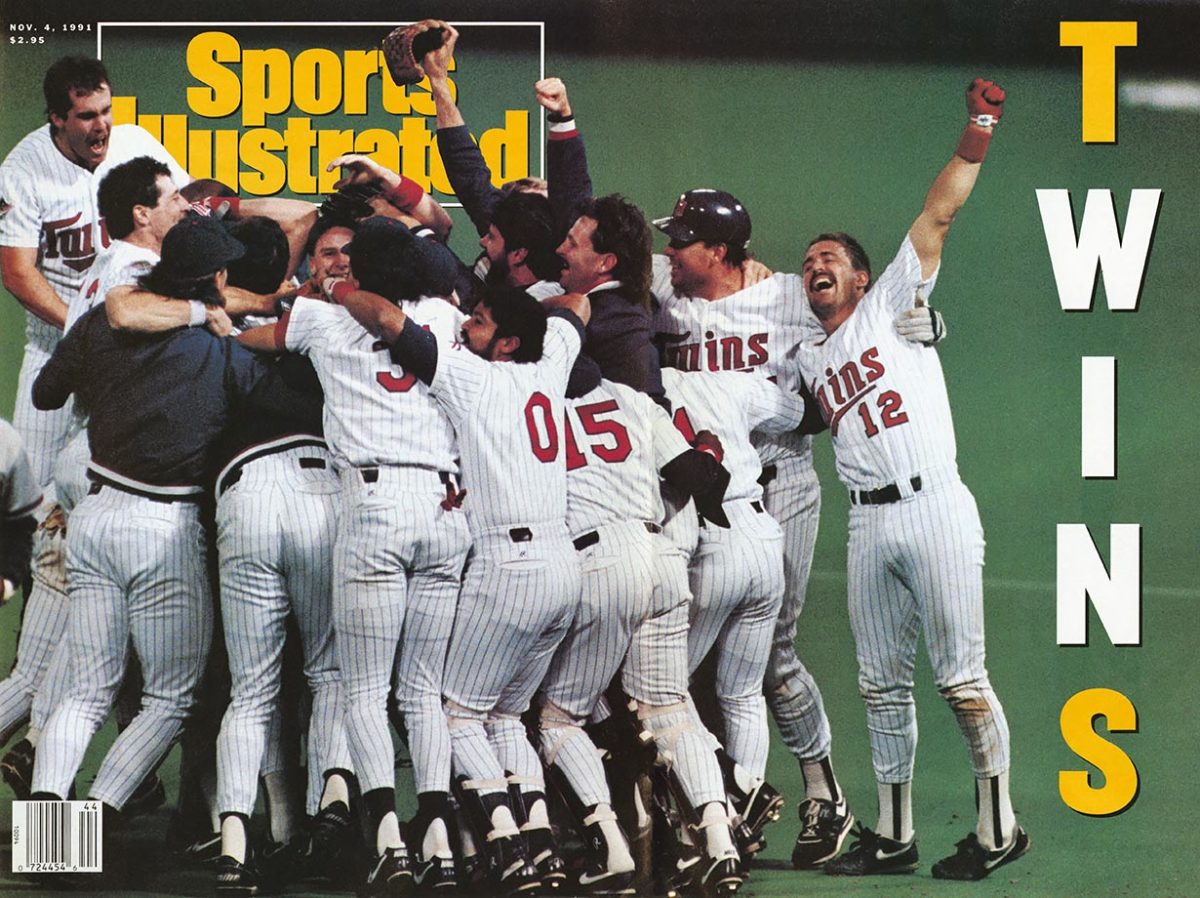

Minnesota Twins last won in 1991

3. News and Notes

• Welcome to the 2016 postseason, otherwise known as The Parade of Pitchers. There have been 119 pitchers used in 14 games, or 8.5 pitchers per game. Relievers have chewed up 45% of the outs. The starters have been horrible (7–10, 4.82 ERA) and the many relievers have been numbingly efficient (7–4, 2.11).

• Now here’s the down side to all these power bullpen arms shutting offenses down: They’re draining pace and action out of games. Here are the totals for the three games between Washington and Los Angeles: 713 minutes (an average of 3:58), 60 strikeouts, 26 pitching changes ... and zero quality starts. In Game 3, there were 351 pitches and only 49 balls put into play. On average, a ball was put into play only once every five minutes, eight seconds.

Bullpens the story as Nationals beat Dodgers in Game 3 to take NLDS lead

• Nationals rightfielder Bryce Harper has hit one home run in his past 103 at-bats, but in the NLDS he has looked as strong as he has since April. Harper, who lost weight over the grind of the season—partly due to injuries that limited his weight training—added weight in the past three weeks. He’s no longer playing a shallow rightfield (which he did to protect his compromised right shoulder) and has been an impact runner on the bases. Harper has stolen a base, dashed from first to third on a single and been thrown out at home trying to score on a pop fly to leftfield. In Game 3, he went from first to home on a double, plowing right through a stop sign at third base.

• Timing is everything: The Nationals have won one postseason series in their 48-year history—as the Montreal Expos in the 1981 NLDS over Philadelphia. They clinched their only series win exactly 35 years ago today, and on that anniversary they now have a chance at a second.

• This is the 14th game Baker will manage with a chance to close out a series. He is 3–10 in potential clinchers.

• The Dodgers’ problems against lefthanded pitching have been too systemic to be considered a fluke. Joc Pederson, a .125 hitter against lefties with eight hits all year against them, actually started a playoff game against a lefty. Until this year, no team ever made the postseason hitting worse than .230 against lefthanders; Los Angeles hit .215. Washington's southpaws have a 2.70 ERA in this series (three runs in 10 innings).

• The Rangers, still without a World Series title, are building a legacy of epic postseason losses. A Dean Palmer walk-off error in the 1996 ALDS; a Nelson Cruz defensive lapse in the 2011 World Series; the three botched infield plays in the 2015 ALDS. And now, a breakdown in triplicate to kick away the 2016 ALDS: a poor feed by shortstop Elvis Andrus, a bad pivot throw by second baseman Rougned Odor and a failed pick and throw by first baseman Mitch Moreland turned what could have been an inning-ending double play into a 7–6 loss to the Blue Jays in Game 3 on Sunday. The Rangers are now 1–8 all time when they have faced elimination.