Looking back on Maris' record-breaking homer 50 years ago

What a strange setting.

The most glamorous record in sports was about to fall, yet the stands at Yankee Stadium were less than half-filled. The record was being chased by a man about whom many baseball fans seemed ambivalent if not downright hostile.

And the commissioner of baseball, then the nation's most popular sport, appeared more interested in preserving the past than in promoting the present.

This was the backdrop 50 years ago, on Oct. 1, 1961, as New York Yankees outfielder Roger Maris took his final crack at breaking Babe Ruth's record of 60 home runs in a season.

What was going on?

Let's go back a few months to when Yankees teammates Maris and Mickey Mantle began challenging the Bambino's record, right there in the House That Ruth Built. A nation was captivated.

Maris and Mantle, the M & M Boys, were front-page news, not only in sports sections but also on the front pages around the country. They were on the cover of Life magazine, a huge deal in that era.

At a time when professional football had yet to dominate the sporting landscape and when both the NBA and college basketball were niche sports, baseball truly was the national pastime. Maris and Mantle were playing for the sport's premier team in the nation's premier city chasing their sport's premier record set by the game's premier personality.

Mantle was one of the most famous athletes in the country. He had won the Triple Crown in 1956, two American League MVP awards and had played on five World Series championship teams.

Maris, playing in only his second season as a Yankee after stops in Cleveland and Kansas City, was not nearly as well known. The 27-year-old North Dakotan was a quiet man who didn't care much for the bright lights of the big city. He also didn't care much for interviews and wasn't exactly Jackie Gleason in front of TV cameras.

Maris' season-long pursuit and ultimate conquest of Ruth's record (illness and an infected hip knocked Mantle out of the race with 54 homers in September) was a dynamic story but it proved bittersweet. Maris ended up battling not only American League pitchers but also public opinion and, sadly, baseball itself.

Instead of celebrating Maris for what he was, a soft-spoken well-rounded ballplayer who would do anything to help the Yankees win, he was criticized for what he wasn't, a colorful fun-loving character like Ruth or the skirt-chasing, hard-drinking Mantle.

Some baseball purists, such as Hall of Famer Rogers Hornsby, ripped his low batting average (.269). Totally ignored in those rudimentary days of baseball statistics was Maris' outstanding OPS (on base percentage plus slugging percentage) of .997. In the field and on the bases, Maris was superb.

"Roger was such a good all-around player," said Hall of Fame catcher and former Yankees teammate Yogi Berra in an e-mail. "He could run, field, throw, everything."

Bill Skowron, the Yankees' first baseman who hit a career-best 28 home runs in 1961, seconded Berra's opinion.

"Roger was a complete player," Skowron said. "He was one of the best defensive players and he had a great arm. On the bases he could break up the double play. He saved me from hitting into a lot of double plays by sliding so hard into second base.''

*****

In July 1961 Maris' (and Mantle's) home runs began drawing the notice of baseball officials. So did the new 162-game schedule. For the first time since the American League began play in 1901, the league had expanded to 10 teams, from eight, and the schedule had grown to 162 games, from 154.

No one thought much about this extension until midway through the season when sportswriters began to speculate whether the eight extra games might help Maris or Mantle chase down Ruth.

Even though he had played his last game in 1935 and had been dead for 13 years, Ruth's legacy continued to dominate baseball. There were veteran writers who as young men had covered Ruth. To them his record of 60 home runs set in the 1927 was sacrosanct.

One of those men was Commissioner Ford Frick. A former sportswriter, Frick spoke often of his friendship with Ruth. He had ghostwritten Ruth's autobiography and liked to remind fans that he was at the Babe's bedside the day before he died.

The commissioner convened a conference of baseball writers to discuss what would happen if Maris or Mantle broke Ruth's record after 154 games. Would that be fair?

No one mentioned that when Ruth established his first home run record of 29 in 1919 he had broken the ancient mark of 27 that was set by Ned Williamson in a 113-game schedule in 1884. And certainly no one argued that baseball was a whites-only game when Ruth played.

Frick could have dismissed the doubters and simply said, "a season is a season" and that would have been that. But Frick ruled that if Ruth's record was broken after 154 games a special designation, what came to be known as the asterisk, would be placed alongside that player's name.

(The NFL, which expanded to 14 games from 12 that same year, had no such problem with its record keeping. When the Philadelphia Eagles' Sonny Jurgensen threw 32 touchdown passes in 14 games that fall, he was given equal billing in the record book with Johnny Unitas who had thrown 32 touchdown passes in only 12 games).

Undeterred, the 6-foot, 200-pound Maris kept slugging. He had 40 homers at the end of July and 51 through August.

In each city, dozens of newspaper and magazine writers sought interviews with Maris. TV and radio stations were part of the pack. Some of the questions had nothing to do with baseball.

Maris told me in 1981 how one reporter asked him if he fooled around on the road.

"Of course not," Maris answered. "I'm married."

"Well, I'm married," the reporter said, "and I fool around on the road."

By September, Maris began losing small patches of hair.

On Sept. 2, against the second-place Detroit Tigers, he slammed Nos. 52 and 53 to ignite a 7-2 victory. In Billy Crystal's 61*, a mostly sympathetic documentary of Maris' record pursuit, the movie's account of that day is off base. Crystal showed the Yankee Stadium crowd jeering Maris after his 53rd homer as if he were Fidel Castro.

I was at Yankee Stadium that day and exactly the opposite happened. When that second homer cleared the rightfield wall, the crowd of 50,000 exploded with cheers. They were thrilled for Maris and thrilled that the Yankees were about to extend their lead in the standings over Detroit. Any boos were easily drowned out.

Yes, most Yankees fans -- as well as Maris' Yankees teammates -- would have preferred Mantle to break the record. The Mick was in his 11th season in pinstripes while Maris was only in his second. However, this didn't mean that Maris' teammates didn't appreciate his accomplishments.

"Roger was a real good guy around us," Berra said in his e-mail.

Game 154 brought the Yankees to Baltimore, Ruth's hometown. Maris had 58 homers, meaning he needed two more to tie Ruth and three to break the record. In what Maris biographer and longtime baseball writer Maury Allen called the best performance under pressure he had ever seen, Maris responded like a champion.

He hit what looked to be No. 59 in the first inning, only to see 23 m.p.h. winds from Hurricane Esther blow the ball foul. In the fourth inning he did hit No. 59. And in the seventh inning Maris blasted a shot that on another night would have been No. 60. Instead, the wind knocked down the ball and it was caught in front of the rightfield fence.

The Yankees won 4-2, clinching the American League pennant, but Maris' record run was officially over. At least that's what Frick and his supporters wanted fans to believe. It's as if they were saying to fans, "Nothing to see here, folks. Check back with us for the World Series"

*****

Instead of capacity crowds flocking to see if Maris could beat Ruth, he finished the 1961 season in front of sparse audiences at Yankee Stadium. A mere 19,401 fans saw him hit No. 60 against Baltimore on Sept. 26.

Only 23,154 were on hand for the final game of the season, on Oct. 1 against the Red Sox. Many fans congregated in the rightfield stands hoping to cash in on the $5,000 reward that a California restaurant owner was offering to anyone who caught the record breaker.

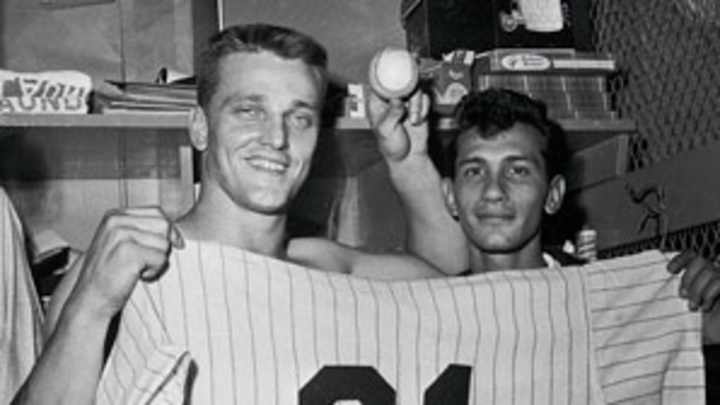

Maris delivered in the fourth inning, lining No. 61 into the rightfield grandstand and making truck driver Sal Durante of Brooklyn $5,000 richer. The Yankee Stadium crowd couldn't have cared less about Frick. They cheered and cheered until Maris came out of the dugout for a curtain call, a shockingly rare occurrence for a ballplayer in the 1960s.

"This is most unusual," exclaimed longtime Yankees broadcaster Mel Allen.

Maris added a grace note to the '61 season when his ninth-inning home run beat the Cincinnati Reds 3-2 in Game 3 of the World Series. The New York Daily News hailed it as "No. 62" and Maris called it his most important homer of the year. The Yankees went on to win the Series in five games.

Many fans, such as president John F. Kennedy who welcomed Maris to the White House, applauded his achievement. Others weren't so sure.

There was talk that expansion had watered down American League pitching, even though AL hitters had batted .256 in '61, barely up from .255 in '60. The league ERA climbed from 3.87 in '60 to 4.02 in '61 but it was well under the 4.16 in '56, Mantle's Triple Crown season.

It was fine for Ted Williams to be the last .400 hitter because he was the Splendid Splinter. Who but the great Joe DiMaggio, the Yankee Clipper, could hit in 56 straight games? And Babe Ruth should hold the home run record because, after all, he was the Sultan of Swat.

Of course, there was a lot more to Maris than those 61 homers. He was the 1960 American League MVP after slugging 39 homers and driving in 112 runs despite missing three weeks with a rib injury. He hit 33 homers and drove in 100 runs in '62.

In the '62 World Series against the San Francisco Giants, Maris helped win the Fall Classic with two plays that don't show up in any box score.

It's been well documented how in Game 7, with the Yankees holding a 1-0 lead in the ninth inning, Maris cut off Willie Mays' two-out double down the rightfield line and fired a perfect relay to second baseman Bobby Richardson to keep Matty Alou at third base. Moments later Willie McCovey lined out to Richardson to end the Series.

Less remembered is his base running gem that helped the Yankees win Game 3. In the seventh inning's Maris' two-run single had put New York up 2-0. He went to second base when McCovey couldn't handle the relay from rightfield.

Elston Howard then lifted a fly ball to Mays in medium right center. No one was supposed to run on the Say Hey Kid but Maris noticed that Howard's fly was drifting to right, taking Mays away from third base. Maris tagged up, took off for third and beat Mays' throw. He then scored on Clete Boyer's grounder for a 3-0 Yankees lead.

That run became crucial in the ninth inning when the Giants rallied for two runs before falling short, 3-2.

Maris also keyed the Yankees' 21-8 stretch drive to the 1964 AL pennant. After being traded to St. Louis, he batted. 385 and drove in seven runs in the 1967 World Series to help the Cardinals beat the Red Sox in seven games.

He played for seven pennant winners and three world champions and certainly wasn't the sullen, brooding ballplayer often portrayed in the media.

"Roger was a real good guy," Berra wrote in an e-mail. "He was a good family man. I played in his golf tournament in North Dakota. He was a good man."

Maris retired after the '68 season and moved to Gainesville, Fla., where he owned a beer distributorship. He slowly began making his way back into baseball, appearing at in old-timers' games and finally returning to Yankee Stadium in 1984 for a ceremony that retired his No. 9 and placed his plaque in Monument Park.

He died in December 1985 of Hodgkin's lymphoma at the age of 51. Six years later Commissioner Fay Vincent ruled that Maris was Major League Baseball's single-season home run record holder. His record stood until Mark McGwire blasted 70 homers in 1998. Barry Bonds hit 73 in 2001.

Both McGwire and Bonds later admitted to using performance enhancing drugs, although Bonds argued that he did so inadvertently.

*****

Maris never hit more than 39 homers in another season and his 61 were called a fluke. Today it might be classified as a sports outlier. The unexpected does happen in athletics, for teams and individuals.

Bob Beamon had never jumped farther than 27 feet, 4 3/4 inches but, aided by altitude and the maximum allowable wind, he soared past 29 feet at the 1968 Mexico City Olympics.

The 1969 New York Mets, the 1980 U.S. Olympic hockey team and the 1983 North Carolina State basketball team all far outperformed expectations. There was no way the New York Giants could defeat the unbeaten New England Patriots in the 2008 Super Bowl but they did.

Baseball, in particular, is filled with outlier performances. Pittsburgh's Chief Wilson holds the single-season record for triples with an astonishing 36 in 1912. He never hit more than 14 in any other season. The Red Sox's Earl Webb holds the record for doubles with 67 in 1931. His next highest total was 30.

Five Octobers before No. 61, a sub-.500 pitcher with a fondness for after-hours activities named Don Larsen threw a perfect game against the powerhouse Brooklyn Dodgers in the 1956 World Series.

Roger Maris had the misfortune to challenge the sainted Babe Ruth and for many older baseball fans and writers that was unacceptable.

These days Ruth remains a beloved figure but he's no longer cast in marble and he's certainly no saint. His many vices, always covered up during his playing days, have become part of his biography. His career home-run record has been surpassed twice and he no longer holds the single-season mark for slugging percentage.

Maris, whose main vice was said to be "too many Marlboros," has come off looking good after the steroids era rewrote (many would say stained) baseball's record book. He still holds the American League record for homers.

Berra said, "I don't want to get into [the debate]" about whether Maris is the true single-season home run king. Bill Skowron sees it differently.

"I would say that [Maris holds the record]. That's my opinion," Skowron said. "These other guys were on the steroids. But that's not my business. I'm 80 years old. Where am I going?"

Regardless of where baseball fans stand on Maris' record status, his 1961 season, over time, has come to be appreciated as one of the outstanding achievements in American sports.

Like the Mercury astronauts of the early '60s, who were pushing into outer space as his home runs were soaring in inner space, Roger Maris was a crew-cut straight shooter who completed his mission. He was the rightfielder with the right stuff.