Stan Mikita's legacy and grace endure even as dementia afflicts the Blackhawks legend

He is skating, always skating, cast in bronze and frozen in time. His hands cradle the hockey stick, detailed down to his custom curve. The number on the home red sweater is 21, captain’s C on the chest. Hair slicked, neck muscles tensed, knees bent, gaze locked, he appears to be moving with purpose. The sculptor made fitting choices with these details. This was—no, this is—Stan Mikita.

The Blackhawks unveiled the statue in October 2011, outside Gate 3½ at Chicago’s United Center. The credentials for canonization are etched into the base. The list is long, and the font is small: 22 NHL seasons, all in Chicago, a team record like his 1,467 points and 926 assists. More games (1,394) than any European-born player in league history, spanning four decades and six U.S. Presidents. Seven-time first-team all-star; only player ever to win the Hart, Art Ross and Lady Byng trophies in one year (twice); Stanley Cup champion in ’61; Hockey Hall of Fame inductee in ’83…

And yet, one life-sized monument to the sinewy center somehow falls short in measuring his full legacy. For that, we require more metal. Certainly another statue belongs at Kemper Lakes Golf Club, where for six years he paid equal attention to repairing swings and divots. Commission one, too, for his philanthropic work, particularly with Special Olympians and hearing-impaired hockey players. Heck, erect a fourth in his old Chicago-area neighborhood, where he cleared so many snow-covered driveways without anyone ever asking; and a fifth in present-day Slovakia, where he lived until age 8, destined to become the first European native in the NHL. There is, however, no need to build a monument to his contribution to Hollywood; it’s already been done. Comedy fans will forever recall the 12-foot-tall figure gliding atop the fictitious donut haunt in suburban Illinois.

“It just resonates,” says Doug Wilson, Mikita’s former Blackhawks teammate and longtime friend, “what he did for the game and what he did for all us.”

Stan Mikita is 76 years old now. Aside from some gray hairs dotting his temples, he still very much resembles the statue outside United Center—5’ 9”, athletic and usually laser-focused. “Wiry strong, like a wrestler,” says Chris, the youngest of Mikita’s four children. But these are only physical traits, what the world can see from the outside. In his mind, Mikita cannot recall what he did for the game, what he did for Wilson, what resonates with everyone else. Suffering from dementia, he’s been left with only a select few.

But if the utter cruelty of his condition makes him forget, at least some beauty can be found through the many who still remember.

Mike Myers riffs on Stan Mikita's Donuts, the iconic shop from 'Wayne's World'

In November 1969, Cliff Koroll was two months into his first season with the Blackhawks. One day in the locker room, Mikita approached Koroll, then 23 years old and the new right-winger on his line. “Come with me,” Mikita ordered. By then he had already led the NHL in scoring four times, won two MVPs and hoisted the Stanley Cup. Koroll simply suspected that a veteran superstar wanted to treat him to lunch and beers. Instead, Mikita drove them to a local church, where over the next several hours they raised funds by signing autographs and posing for pictures. As Koroll remembers, once they were done—the parish served lunch, but no beer—Mikita again approached. He jabbed one finger into the rookie’s chest and said, “This is what you have to do. This is part of your responsibility.”

The family believes such ethos stems from his humble beginnings. “He lived his life never forgetting where he came from,” says Scott, Mikita’s second child. Born Stanislav Gvoth in 1940, he was raised on a small farming community in rural Czechoslovakia, where food grew in the garden, water rose from an outdoor pump and German soldiers occupied his bungalow home during World War II. Just before Christmas 1948, he was adopted by Anna and Joe Mikita, his aunt and uncle, and moved to the Toronto suburb. Shortening his name to Stan, he enrolled in third grade despite knowing no English. This made him a target for bullies, who derisively nicknamed him “DP,” for “Displaced Person.”

In hockey Stan found an outlet for lashing back. “I don’t know where my aggression stemmed from,” he wrote in his 2011 book, Forever A Blackhawk, “but it might have had something to do with feeling like an outsider for so long.” After making his NHL debut at age 18, Mikita topped 100 penalty minutes in his first two seasons. Quick to run his mouth, quicker to drop his gloves, he then hit 97 in year three. Even as he led the league in scoring in 1963–64 and ’64–65, he also spent five whole hours in the penalty box. A hefty chunk of those were misconducts, usually for retaliating against opponents who were eager to run the 160-pounder. “That’s how he exhibited his anxiety,” his wife, Jill, says today, “was by fighting.”

Off the ice, it had the opposite effect. “[He was] sensitive to being the person who’s different,” says Meg, his oldest daughter. “He knew how it felt. He never made anyone feel like that.” The Mikita children remember volunteering as finish-line huggers for races at the Special Olympics, which Stan had helped bring to Chicago. He later founded the Stan Mikita School for Hearing Impaired, inspired by a friend’s deaf son who was an aspiring goalie. The annual summer camp still runs today. “Predicated on empathy,” says Mike Mullins, one of Stan’s closest friends. “He told me that he might as well have been deaf when he started playing hockey.”

Today, Koroll serves as president of the Blackhawks Alumni Association. For the past three decades, the organization has hosted an annual golf tournament named in Mikita’s honor. Sometimes, Koroll gets booked for speaking engagements. He tells the church story at every turn. “Greatest lesson I learned from him,” Koroll says. “I learned a lot on and off the ice, but that’s the best gift he could’ve given me.”

Sports Illustrated's 10 greatest hockey stories

The pacification began with an infant’s wisdom. At least, that’s how the story goes.

One afternoon in 1965, the Blackhawks were playing the Rangers. Again, Mikita had been banished into the sin bin. Watching on TV from their apartment, 14-month-old Meg wondered aloud why daddy always sat by himself and never with his friends on the bench. “I said, ‘Because he did something he wasn’t supposed to do,’” Jill says. “She proceeded to ask him the same question when he came home.”

Seemingly as easy as stopping on an edge, Mikita changed his attitude. He quit yapping to referees, reduced stick fouls like slashing and spearing, cut back on the revenge missions. As a result, his penalty minutes plummeted: 154 in 1964–65, to 58 a year later. In the following two seasons, he collected an astonishingly low 12 and 14 minutes, respectively, netting him consecutive Lady Byng awards for gentlemanly play. Paired with back-to-back scoring titles and MVP honors, earned despite playing in the shadow of Bobby Hull, Mikita is still history’s only winner of that particular trophy trifecta. “He was feared and respected,” Wilson says. “He could play any way that you wanted.”

Classic Photos of Stan Mikita

Stan Mikita poses for a photo circa 1963.

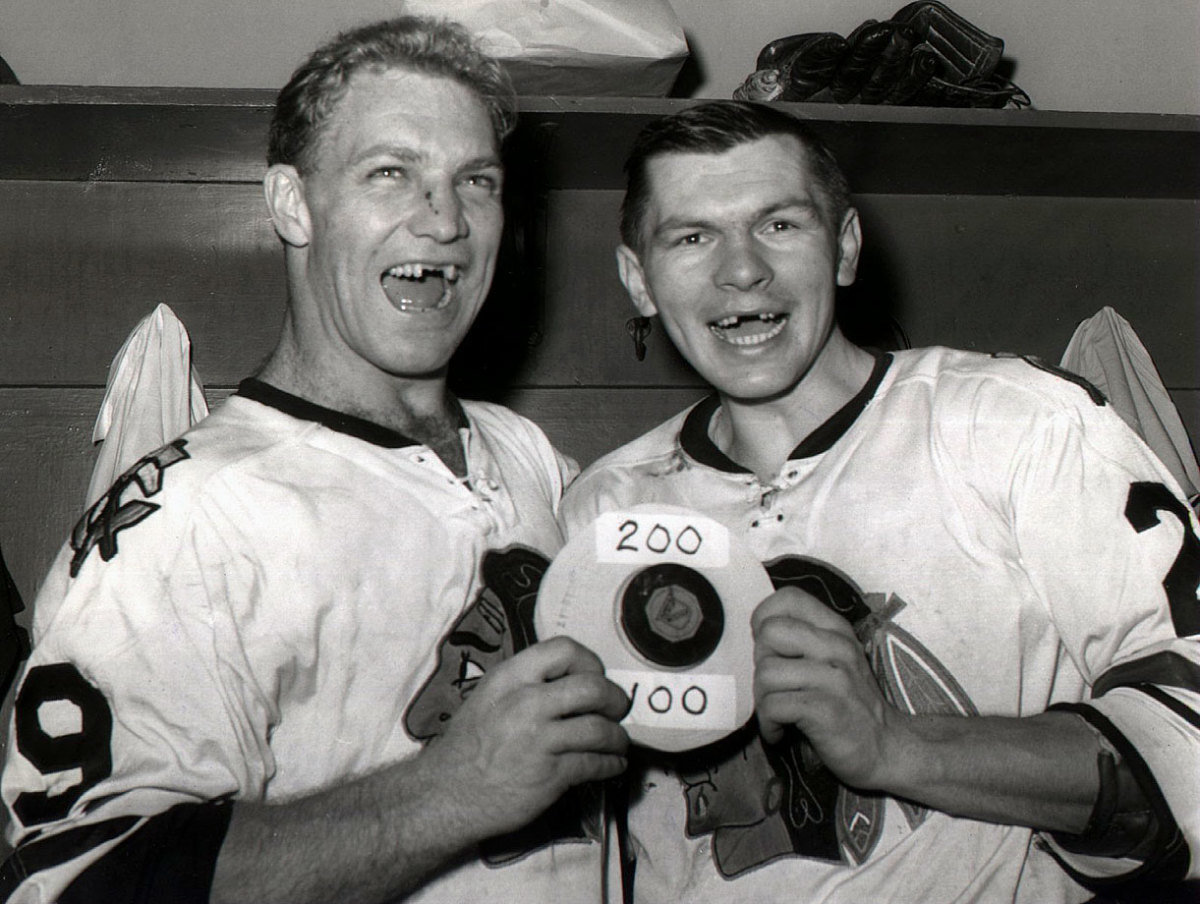

Bobby Hull and Stan Mikita pose together after Hull scored his 200th career goal in the same game Mikita score his 100th career goal during the 1963-64 season.

Stan Mikita celebrates after scoring a goal past Eddie Johnston during the Chicago Blackhawks game against the Boston Bruins on Jan. 23, 1964 at Boston Garden.

Tim Horton defends against Stan Mikita during the Chicago Blackhawks game against the Toronto Maple Leafs circa 1965.

Stan Mikita shoots the puck during the Chicago Blackhawks game against the New York Rangers on Jan. 8, 1966 at Madison Square Garden in New York City.

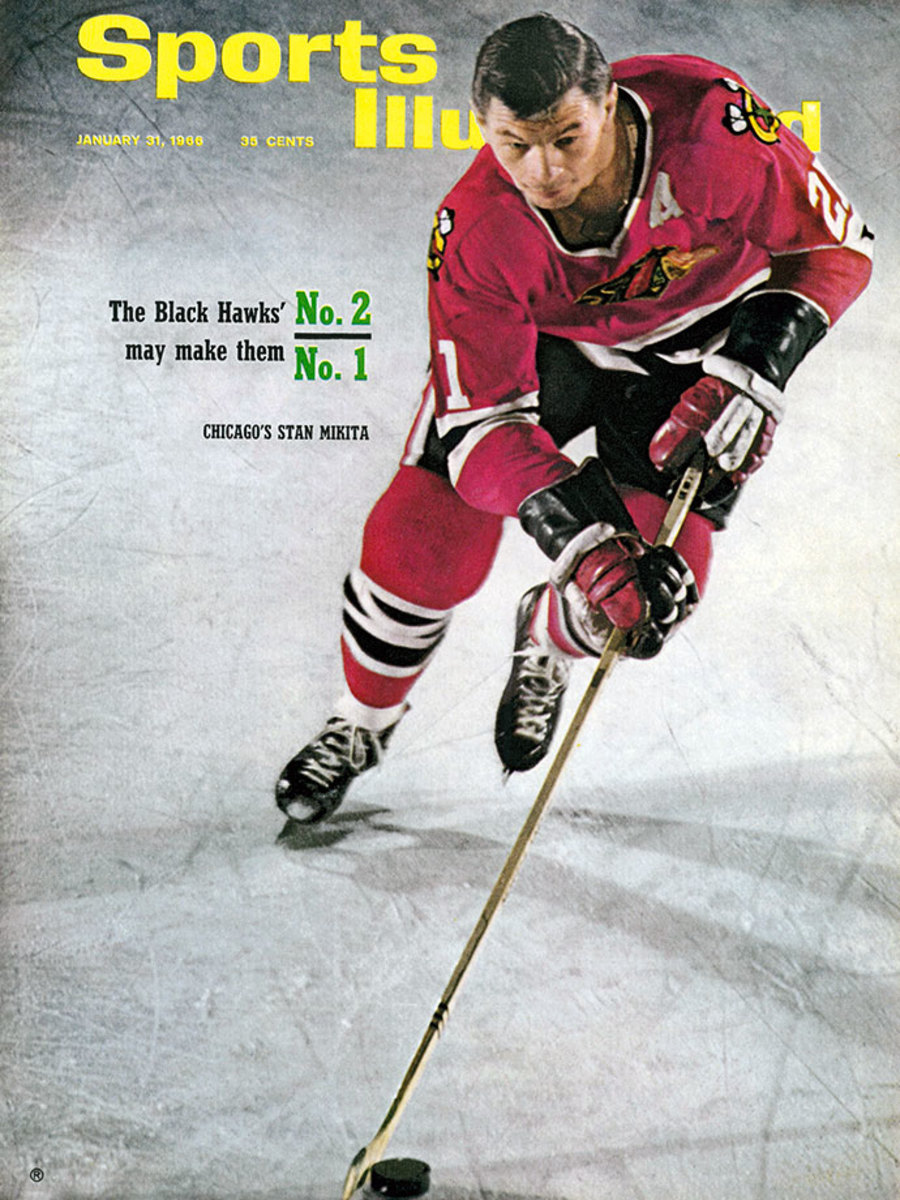

Stan Mikita appears on the Jan. 31, 1966 cover of Sports Illustrated.

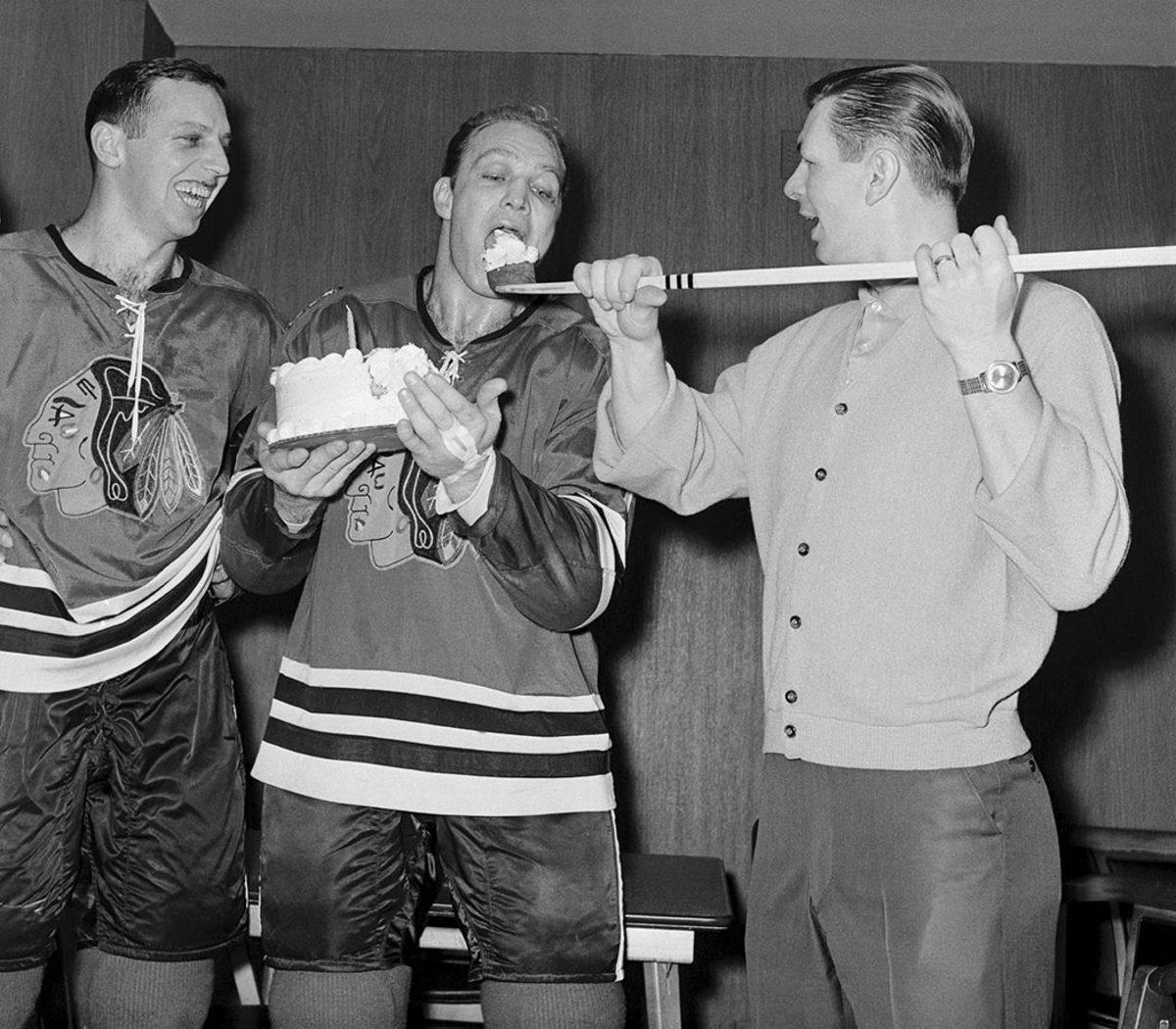

Stan Mikita uses a hockey stick to serve up a piece of birthday cake to teammate Bobby Hull during a small celebration for Hull's 28th birthday, one day late, on Jan. 4, 1967 at Chicago Stadium.

Stan Mikita looks on from the bench during the Chicago Blackhawks game against the Boston Bruins on Feb. 25, 1967 at Chicago Stadium.

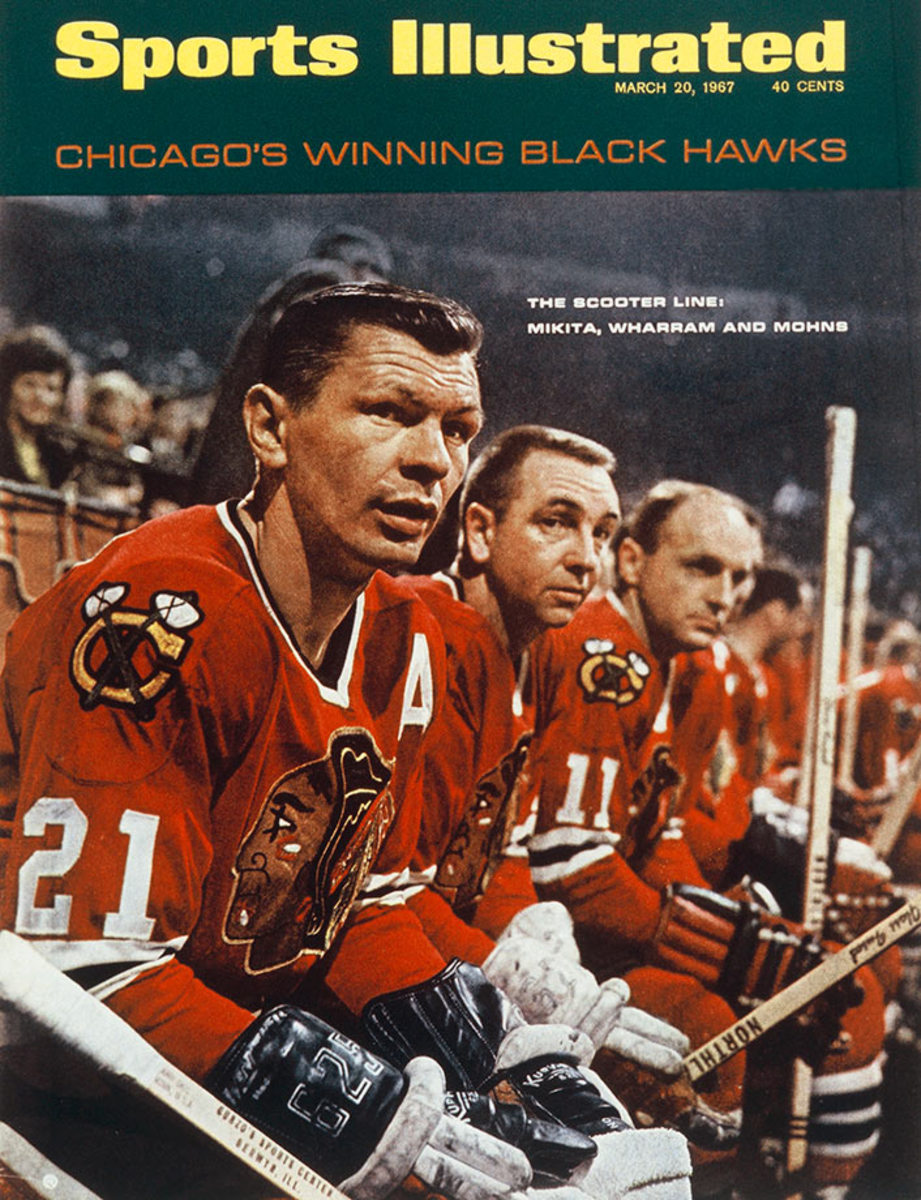

Stan Mikita, Kenny Wharram and Doug Mohns appear on the March 20, 1967 cover of Sports Illustrated.

Stan Mikita poses with four pucks after his four goal game in the Chicago Blackhawks 7-2 win over the Pittsburgh Penguins on Dec. 6, 1967 at Chicago Stadium.

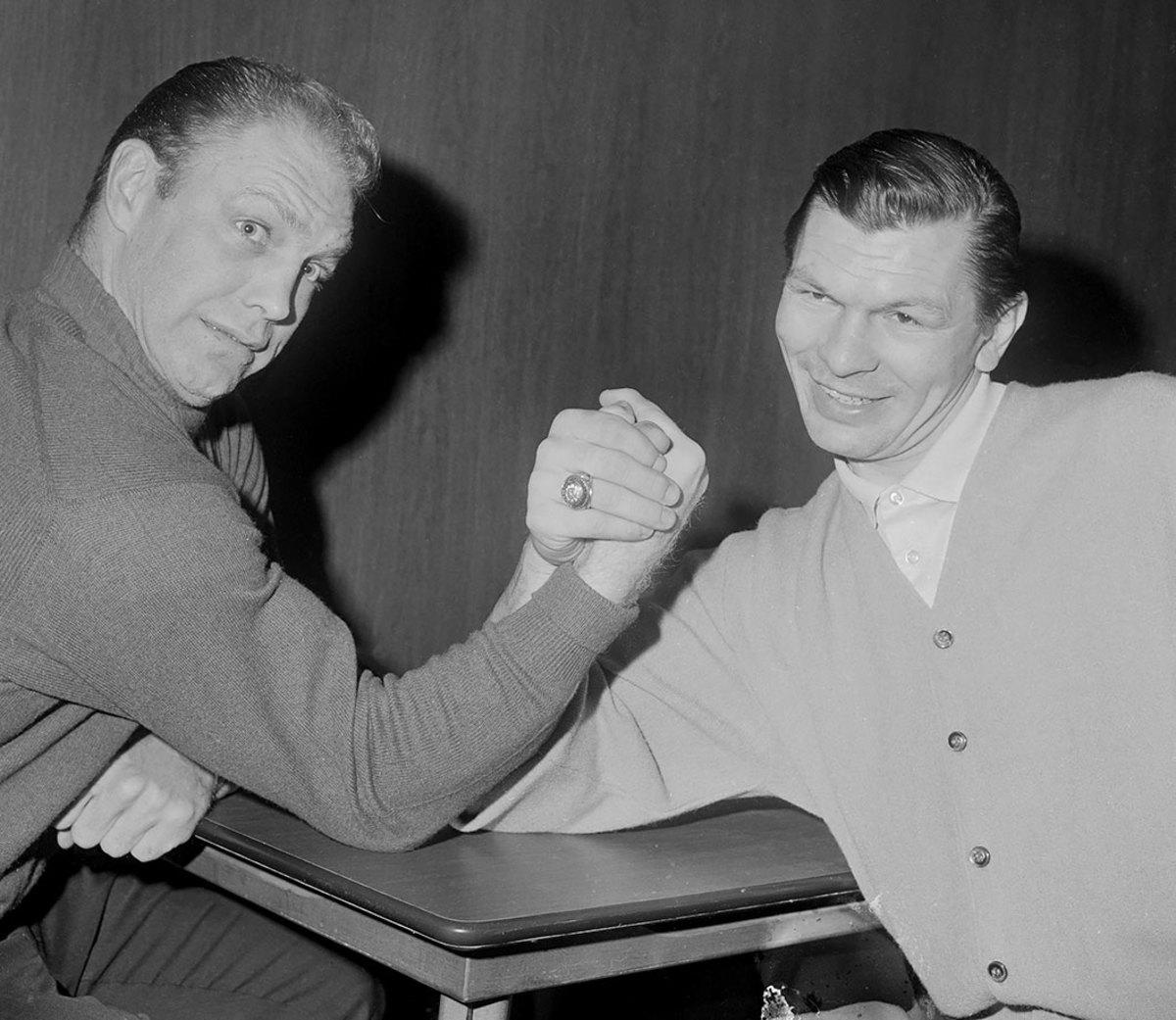

Bobby Hull and Stan Mikita, tied for the NHL scoring lead midway through the season with 48 points each, appear to be settling their friendly battle by arm wrestling prior to the Chicago Blackhawks game against the New York Rangers on Jan. 10, 1968 at Chicago Stadium.

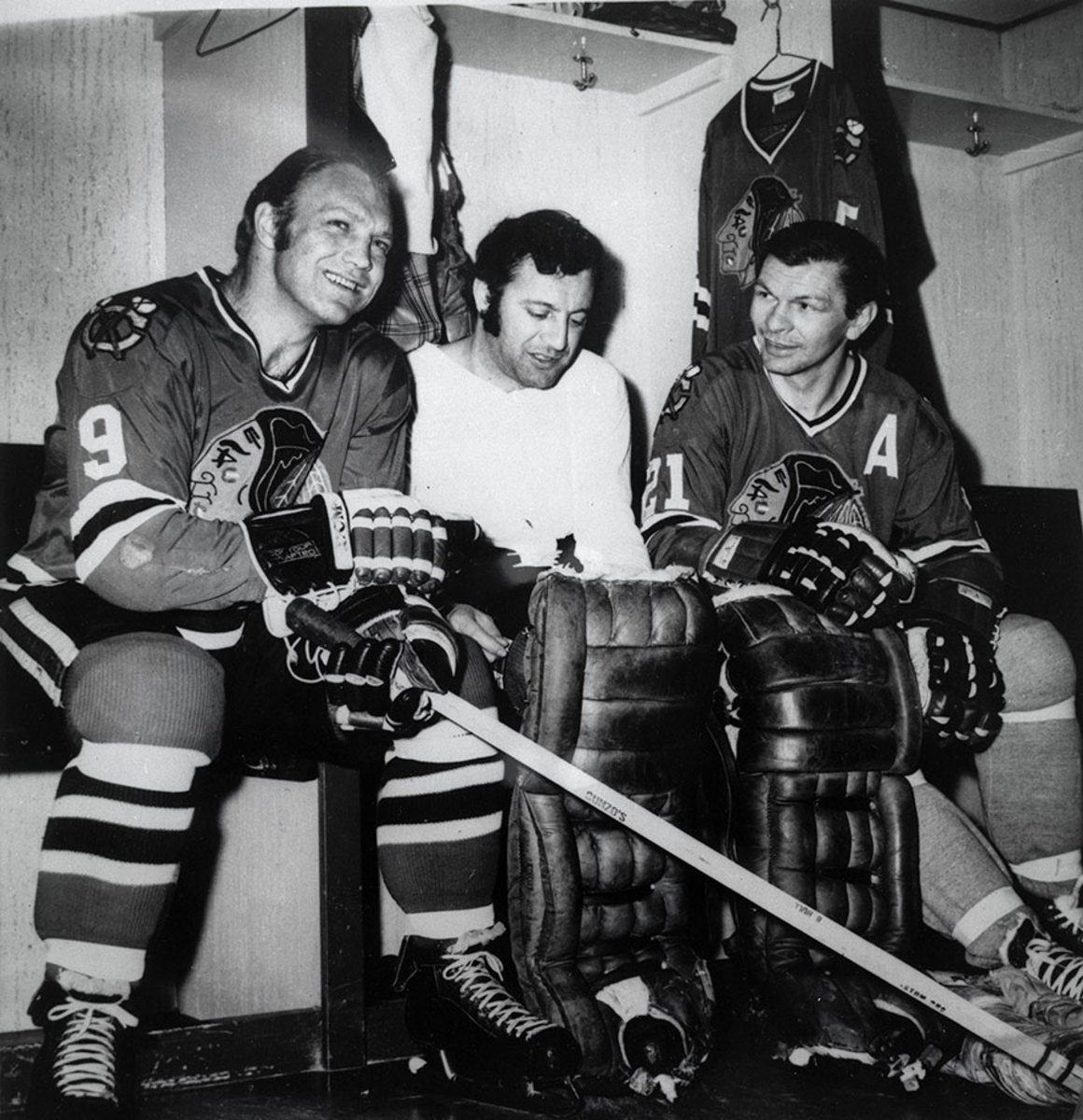

Bobby Hull, Tony Esposito and Stan Mikita, rest after a light workout on May 3, 1971 at Chicago Stadium.

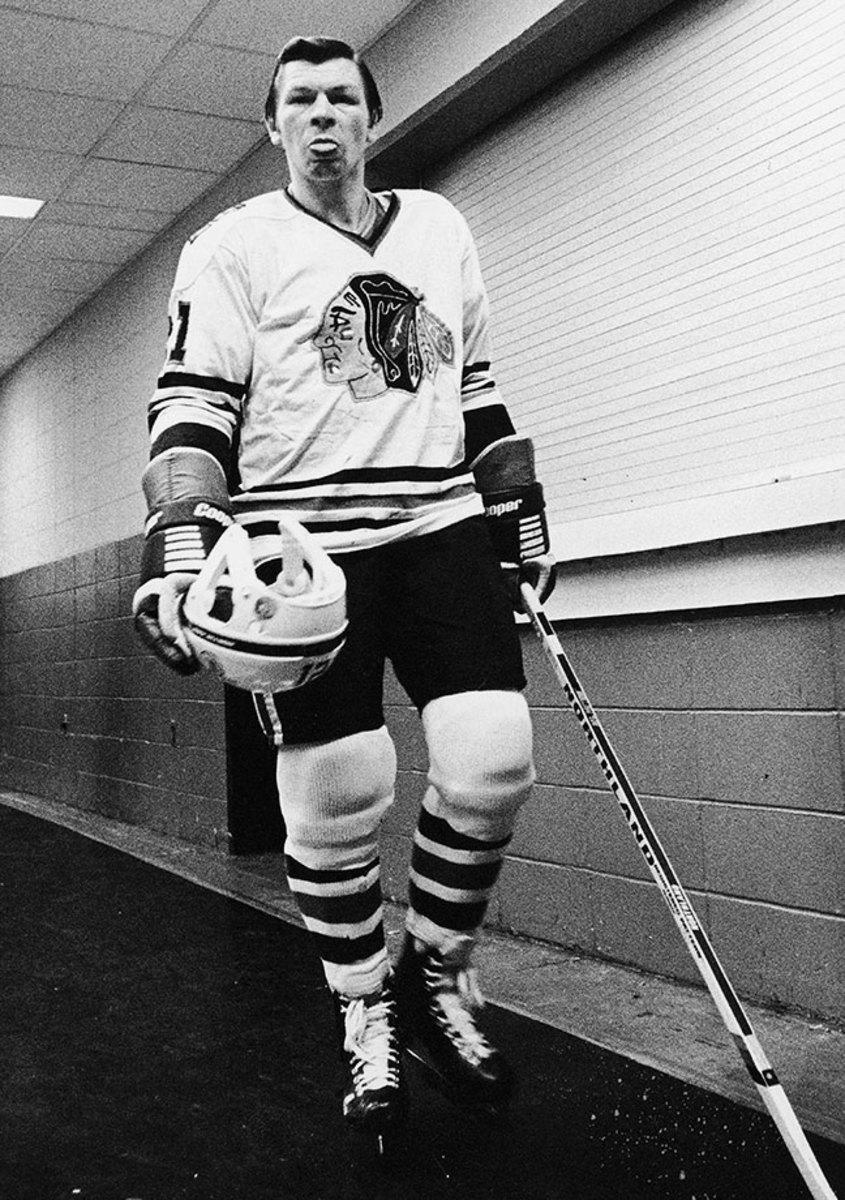

Stan Mikita sticks his tongue out as he walks out to play in the Chicago Blackhawks game against the New York Islanders on Dec. 21, 1974 at the Nassau Coliseum in Uniondale, N.Y.

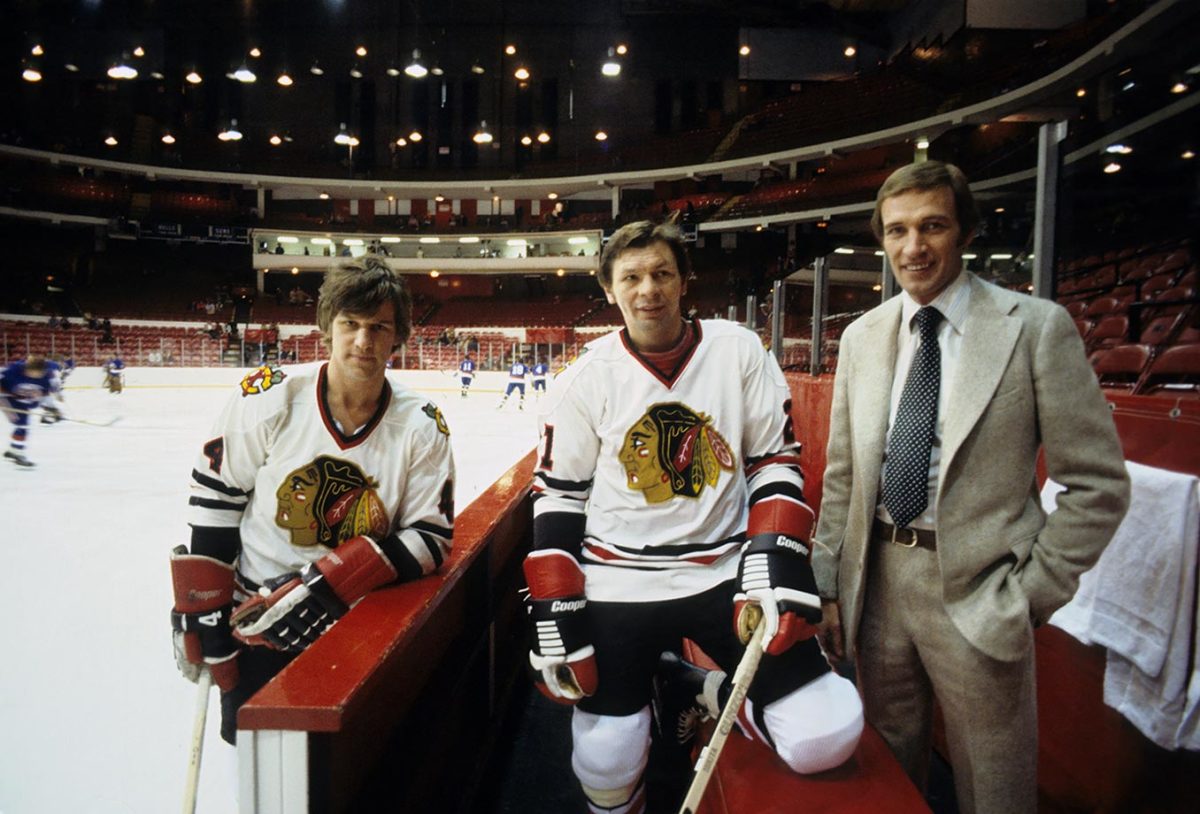

Bobby Orr, Stan Mikita and coach Bill White pose together before the Chicago Blackhawks game against the New York Islanders on Jan. 12, 1977 at Chicago Stadium.

Stan Mikita acknowledges the crowd during a pre-game ceremony honoring Mikita and Bobby Hull before the Chicago Blackhawks game against the San Jose Sharks on March 7, 2008 at the United Center in Chicago.

Stan Mikita is greeted by fans after arriving for the Chicago Blackhawks home opener against the Nashville Predators on Oct. 13, 2008 at the United Center in Chicago.

Stan Mikita smiles while attending the Chicago Blackhawks home opener against the Nashville Predators on Oct. 13, 2008 at the United Center in Chicago.

Stan Mikita and Bobby Hull skate together while lined up with the Chicago Blackhawks Legends team prior to the Blackhawks home opener against the Colorado Avalanche on Oct. 10, 2009 at the United Center in Chicago.

Stan Mikita stands in front of his statue after the unveiling of statues honoring Mikita and Bobby Hull prior to the Chicago Blackhawks game against the Colorado Avalanche on Oct. 22, 2011 at the United Center in Chicago.

Bobby Hull, Michael Jordan and Stan Mikita pose together in their suite during Game 6 of the Western Conference Quarterfinals between the Chicago Blackhawks and Phoenix Coyotes on April 23, 2012 at the United Center in Chicago.

Tony Esposito, Bobby Hull, and Stan Mikita pose together in their suite during the Chicago Blackhawks Stadium Series game against the Pittsburgh Penguins on March 1, 2014 at Soldier Field in Chicago.

To those who know him well, the switcheroo from being “a mean little bastard”—Mullins’ words—reflects Mikita’s willpower, a trait Jill recalls seeing during their courtship, when he always seemed to wake her when he called late at night after games. They met in March 1962, got engaged that June and married the following spring. “Persistence,” she clarifies, “but not stalking.” Around the house, he would sign stacks of hockey school letters for hours without any breaks; he’d work on the same crossword puzzle for a week just to see it finished. Midway through his career, doctors advised him to quit smoking after a health scare. Mikita had been puffing since age 12, peaked at a pack a day, and sometimes lit up during intermission of Blackhawks games, but dropped the habit cold turkey. “No patch, no group,” Meg says. “That was it. Once he was determined, he just did it.”

Even upon retiring from hockey in 1980, Mikita rarely let up. Bent on becoming a golf pro, he wore out the family copy of Ben Hogan’s Five Lessons, passed the certification tests, and before long was running Kemper Lakes. (Chris also says his father has hit 21 holes-in-one, “same as his jersey number.”) Since Mikita had bolted Canadian high school one year early for the Blackhawks, he later completed his equivalency degree in Chicago. And then, just to prove that he could’ve succeeded in university, he aced the one business class he took at Elmhurst College. Together Chris and Jane now oversee day-to-day management of Stan Mikita Enterprises, which among other things makes the small sauce containers that accompany chicken nuggets at McDonald’s. “And he didn’t know s--- about the plastics business or the packaging business,” Mullins says. “But he was willing to do the homework, willing to invest the time.”

Indeed, Mikita always figured out life in his own unique way. He certainly did as a kid, during the infancy of his hockey career. Absent any neighborhood street or pond games, Stan would retreat into the basement of his Ontario home. There, alone, he honed his soft hands by stickhandling raw eggs around the concrete floor.

“I’m not sure there was a smarter player who ever played the game.”

That’s Wilson again. Now general manager of the San Jose Sharks, he spent his first three NHL seasons witnessing the end of Mikita’s career with the Blackhawks. Saddled by an aging back, Mikita increasingly relied on veteran guile for survival. Others noticed, too. Teammates recall long conversations with Mikita over lunch – at the bar, not the church – in which he dissected opposing lines and formed scouting reports for faceoffs. “Always strategizing, always thinking ahead,” Koroll says. Meg remembers her father studying geometry, so he could angle passes more efficiently off the boards. “He learned by doing,” says Meg, a special education teacher in the Boston area. “That’s the way he processed it.”

Every so often, though, raw ingenuity struck. Mikita is widely credited with popularizing, if not outright inventing, the practice of curving sticks. The inspiration dawned during a scrimmage, when his blade got caught in the bench door and bent like a banana. Before long, Mikita was borrowing the trainers’ propane gas torch and creating some wicked movement on his shots. “We didn’t like it,” says Glenn Hall, Chicago’s goalie and mercifully masked guinea pig. “The puck wasn’t coming true.”

Strangely enough, that wasn’t even Mikita’s sole lasting impact on NHL equipment trends. In a December 1967 game against Pittsburgh, an errant puck ripped off a chunk of his right ear. Doctors stitched the missing piece back on, so Mikita taped a steel athletic cup to the side of an earless helmet and played the next game. A dozen years before the NHL began mandating protective headgear to new players—and much longer before “concussions” replaced “bell-rungs” as the accepted vernacular—Stan was among the first to start donning domes full-time.

“I think he was a step ahead of everybody,” Koroll says. “Always looking for innovative ideas.” In particular, this translated well into golf. At home, he would strengthen his wrists by fiddling weighted clubs while watching TV. On road trips, Mikita always carried spare shafts to practice regripping, and he was often spotted fine-tuning his shooting form in hotel mirrors. (No wonder Mikita later steadied around a plus-2 handicap.) When he taught lessons at Kemper Lakes, Mikita started memorizing his students’ exact swings, which he later replicated to diagnose hitches. Once, this routine unfolded with balloons stuffed down his shirt, because Jill had suggested it might help more accurately replicate the experience of a female client. “He found great satisfaction when he could help these people,” his wife says.

How the Washington Capitals turned in—and recovered from—the worst NHL season ever

Though thinner boundaries separated superstar from fan during Mikita’s era in general, his natural gentility erased what existed. If autograph-seeking kids rang the doorbell during dinner, in they came while steak and potatoes cooled on his plate. Before leaving Chicago Stadium after games, Mikita would gently remind his family, “Okay, we’re going out here, but you’re going to have to wait a while.” Though Mikita is no longer able to public appearances, the Blackhawks still employ him as an official team ambassador. While he could, herelished the role. “The patience he has for people who are just genuinely interested in him, it was limitless,” Mullins says. “And it was the star asking you questions, instead of the other way around.”

The best example of this took place inside an old florist shop along La Brea Avenue in Hollywood. When Mike Myers was writing his first film, Wayne’s World, the greater Toronto native and lifelong Maple Leafs fan wanted to pay homage to a popular hangout spot from his childhood— Tim Hortons coffee. And since the script took place in Aurora, Ill., and since the main characters would be diehard fans who played street hockey in Blackhawks sweaters, and since in real life Myers always considered Mikita was one of those “defoliants, i.e. they would destroy the Leafs”… Stan Mikita’s Donuts was born.

“We just wished he played for the Leafs, basically,” Myers says. “You couldn’t imagine it not being Stan Mikita’s Donuts. Sometimes when you just wish it, you know that it’s right, the universe rewards, you know?”

Truckloads of custom memorabilia, much of it adorned by Mikita’s smiling face, had already been hauled onto set before someone realized they’d forgotten to get licensing approval from Mikita himself. “We were already knee deep in s--- at that point,” says Wayne’s World director Penelope Spheeris. “We had committed to Stan. He could’ve asked for millions of dollars at that point, and he’d have gotten it.” Instead, when Paramount Pictures called, Mikita merely requested a round-trip ticket to Los Angeles and a cameo.

Mikita only spent one day on the donut shop set, and emerging with just a brief non-speaking role in the final cut. (He sits at the bar counter, back to the camera, wearing a purple shirt.) But even a quarter-century later, Mikita’s brief visit still resonates. “Everything stopped,” Spheeris says. “And that doesn’t happen on a set. Everyone fluttered around him. We had to pay tribute right there.”

“It all seemed like an insane fantastic dream,” Myers says. “It was like, ‘Oh my god, that’s Stan Mikita.’ That’s crazy. He’s just a hero. A great, hunky hero.”

Mikita, on the other hand, left Hollywood with mixed feelings about the moviemaking business. Too many hours spent sitting around with such little to do, he told his family. But Scott also remembers his dad eagerly returning to Chicago with a giant prop box, stuffed with coffee cups and other donut shop swag. That was the best part of the trip, Stan told Scott -- hanging with members of the crew, learning how the set got built, asking questions about how the props were made.

They visit him every day, without fail. Two years ago, Stan Mikita moved into a first-floor apartment of a facility in the greater Chicago area. The family declines to specify his location any further, in the interest of preserving his privacy. There aren’t many hints of his playing days inside the unit, save a Blackhawks calendar hanging on the bedroom wall and a picture of himself with ex-teammates Hall, Hull, and Pierre Pilote. Most everything else—the trifecta trophies, the 1961 Stanley Cup ring, the 500th goal stick from Feb. 27, 1977—lives at home with Jill.

The signs began bubbling earlier this decade, around the time the statue was unveiled outside Gate 3½. First, the family noticed Stan growing quieter in public settings. Then he started forgetting words in conversation or interviews. The most sobering moment was when he stood up at the dinner table and declared, “Okay, I want to go home now,” even though he was already there. Doctors diagnosed dementia with suspected Lewy bodies, named for the anomalous proteins that diffuse throughout the brain and disrupt normal cognitive function. Now most short-term memories disappear within seconds, here and gone quicker than a shift on the ice. Mullins knows. His father battled dementia for five years before passing away. “There’s no happy endings here,” he says. “It’s a long downhill slide.”

The deeply rooted traits remain, though. Some residents at the facility—“Stanleyland,” Mullins calls it—are bound to wheelchairs and walkers. Stan, however, is still constantly on the move. He spends afternoons strolling the hallways, or exploring the outdoor garden, often up to five miles before dusk; the family would know the exact distance, but Stan kept losing the FitBits they bought him. He’s still wiry-like-a-wrestler strong, possessing a grip so fierce that the family nicknamed it: The Claw. He still crushes steak and potatoes. Everyone still gets called by their full name—Robert for Hull, Douglas for Wilson, Michael for Mullins. Though he does not remember his childhood, every so often, without realizing it, he will reflexively revert to speaking Slovak.

Mikita also remains intensely curious, pausing walks to scour the walls for mold or pick up invisible pieces of trash from the carpet. (Hallucinations are one symptom of Lewy body dementia.) He maintains a dry-yet-goofy sense of humor; when his grandchildren visit, he’ll sometimes ask what’s on their shirt and then swipe their noses when they look down. The unflinching politeness hasn’t left, either, even though most everyone seems like a strange. Still, he holds the door open. Still, he shakes your hand. Stan Mikita, how the hell are ya? he might say. That’s a nice blouse. What’re you eating there? Looks yummy.

- Read all of SI's NHL100 content

The bitter irony here is that, because Mikita remains so beloved in the Chicago area, so iconic in the eyes of generations of Blackhawks fans, the family stopped taking him into public, aside from the occasional picnic at a local park. “He’d never want to be seen the way he is right now,” Meg says. “He would be so upset. He can’t be the kind, gregarious, patient man that he was to everybody. He just can’t do it.” Meg remembers a fan once frightening her father at the dentist’s office. The man was well intentioned, hoping to say hello, but Stan recoiled because he wasn’t sure why. “We would much prefer for him to be out there saying hi to everybody,” Meg says. “That’s not the hand we were dealt.”

But they manage. Scott, who has acted in Phantom of the Opera on Broadway for more than 15 years, treats visits like he might acting exercises: “You have to enter his reality and take that as a given circumstance. Every once in a while, his eyes are clear, and he’s there for a second. For like one second. And then he’s gone again into that interior world of whatever’s going on his mind.”

On the best days, Stan’s memory will activate. Then the family sees glimmers of his old self. When the family takes him to Jane’s house, which overlooks a golf course, Stan brings his grandchildren onto the putting green and offers tips on their strokes. After watching the Blackhawks lose to the St. Louis Blues in the 2017 Winter Classic earlier this month, Scott asked the next day if he remembered the game. Yes, Stan replied, “and they looked like crap.” Over the summer, it was a big deal when Jane handed him a signed 8 x 10 picture from his playing days and asked him to autograph it again, which he did “as perfectly as the original signature.”

Last Thanksgiving, the family again gathered for dinner at Jane’s house. At one point, Jane’s 12-year-old son, Billy, emerged from the basement lugging a wooden hockey stick. “Stan,” Billy began—he’s Stan to everyone now, regardless of relation, because “grandpa” and “dad” might confuse him—“could you show me how to stickhandle. Saying nothing, Stan took the stick. He pressed the blade onto the ground, firmly leaning forward to check its flex. Nearby was a rubber ball, which Stan cradled into his control. The moment was perfect. The Chicago living room had transformed into an Ontario basement. The ball had become an egg.