JAWS and the 2013 Hall of Fame ballot: Larry Walker

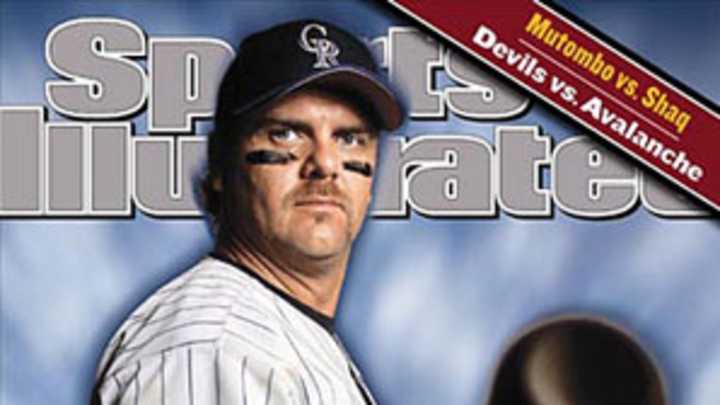

Larry Walker's best years came during his 10 seasons in Colorado from 1995-2004. (Walter Iooss Jr./SI)

The following article is part of my ongoing look at the candidates on the BBWAA 2013 Hall of Fame ballot. For a detailed introduction to JAWS, please see here.

Yet another great outfielder developed by the late, lamented Expos — Andre Dawson, Tim Raines and Vladimir Guerrero being the most notable — Larry Walker was the only one of that group who was actually born and raised in Canada, yet he spent less time playing for the Montreal faithful than any of them.

Walker spent 17 seasons on the major league scene, but missed so much time due to injuries (and of course, the 1994-1995 strike) that 23 other players took more plate appearances during the years spanning his career, even after excluding his 56 plate appearance pre-rookie season. The median players from that group, Gary Sheffield and Marquis Grissom (another fine product of the Montreal system) had 11 percent more plate appearances over the 1990-2005 span. Stretch Walker's career by 11 percent and his case for Cooperstown would be a whole lot stronger. As it is, his relatively short career, high peak and extreme offensive environment put the JAWS system to the test.

Player | Career | Peak | JAWS | G | H | HR | SB | Avg | OBP | SLG | TAv |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Larry Walker | 69.7 | 43.1 | 56.4 | 1988 | 2160 | 383 | 230 | .313 | .400 | .565 | .309 |

AVG HOF RF | 69.5 | 41.3 | 55.4 |

Born in British Columbia, Walker was more focused on playing hockey as a youth, and aspired to be an NHL goalie, honing his skills blocking the shots of friend and future Hockey Hall of Famer Cam Neely. Baseball was a secondary focus for Walker until he was cut from a pair of Junior A teams. He wasn't drafted by a major league baseball team; instead, Expos scouting director Jim Fanning spotted him at a tournament and signed him for a paltry bonus of $1,500 in 1984. Because of his inexperience, he took some time to rise through the minors, his progress further slowed by a knee injury suffered playing winter ball in Mexico. Reconstructive surgery cost him all of the 1988 season, and even in the final year of his career he said that the knee still bothered him.

Walker debuted in the majors in late 1989, and claimed the regular rightfield job the following season, at times playing in an outfield that featured Raines and Grissom. His rate stats weren't much to write home about at first glance (.241/.326/.434) but he did hit 19 homers and steal 21 bases en route to a 3.2 WAR season. He soon emerged as a potent offensive threat thanks to his combination of patience and pop, topping a .300 True Average three times in his five full seasons with the Expos, with another one at .295. He averaged 4.1 WAR per year during that stretch thanks to above-average defense, despite never playing more than 143 games; he served DL stints in 1991 and 1993, and probably wasn't helped by playing on Olympic Stadium's artificial turf.

Walker's most valuable season with the Expos was in 1992, when he hit .301/.353/.506 and was 10 runs above average in the field, good for 5.2 WAR. He was en route to a similarly fine season in 1994; despite a shoulder injury which forced him to first base from late June onward, he hit .322/.394/.587 for the team that had the majors' best record when the players' strike hit. Alas, that marked the end of his time in Montreal; with general manager Kevin Malone under strict orders to cut payroll in the wake of the strike, the Expos didn't even offer Walker arbitration, and he signed with the Rockies.

In Colorado,he stepped into the most favorable hitting environment of the post-World War II era. He hit 36 homers for the wild-card-winning Rockies in 1995, his first season in Denver, to go with a .306/.381/.607 line, but in a 5.4 run per game environment, his True Average — a measure of a player's run production per out on a batting average scale after adjusting for park and league scoring levels, with .300 being very good — actually fell by 31 points from the season before, from .327 to .296.

Walker missed more than two months of the 1996 season due to a broken collarbone and his production suffered, but returned in 1997 and hit an eye-popping .366/.452/.720, leading the league in on-base and slugging percentages as well as home runs (49); Tony Gwynn's .372 batting average led the league, preventing Walker from the rare slash-stat Triple Crown. Still, his 409 total bases were the most since Stan Musial's 429 in 1948; over the next four years, four players — teammate Todd Helton, Barry Bonds, Luis Gonzalez and Sammy Sosa — would reach the 400 total base plateau six times thanks to Coors Field, the higher offensive levels of the era, juiced baseballs and who knows what else. Even after adjusting for the scoring environment, Walker's season was worth an NL-best 9.6 WAR, and he won MVP honors.

Walker won batting titles in each of the next two years, hitting .363/.445/.630 in 1998 and .379/.458/.710 in 1999; all three triple-slash stats led the league in the latter year, putting him in select company as the first player to do it since 1980, but the first of a new wave of players to do it during the game's high-offense years. Missing about 30 games a year in each of those seasons limited him to a combined 10.4 WAR.

After signing a six-year, $75 million extension with the Rockies, Walker continued to battle injuries, missing major time in 2000 but rebounding in 2001 to hit .350/.449/.662 for his third and final batting title. His 38 homers were the second-highest of his career, as was his 7.6 WAR. He played two more relatively full seasons for the Rockies, but spent the first two and a half months of the 2004 season on the disabled list with a groin strain; he came back and played 38 games with Colorado before being traded to the Cardinals in a waiver-period deal. Coming down from altitude, he hit .280/.393/.560 with 11 homers in just 44 games for St. Louis, then hit two homers in each of the three rounds of the postseason as St. Louis made it all the way to the World Series before being swept by the Red Sox. He lasted just one more year, battling a herniated disc in his neck but hitting a very respectable .289/.384/.502 in 100 games.

Is that a Hall of Fame career? Walker's key counting stats (2,160 hits, 383 home runs) are low for the era, particularly when one considers the advantages gained from taking 31 percent of his career plate appearances at Coors Field, where he put up video-game numbers: .381/.462/.710 with 154 homers in 2,501 plate appearances. Elsewhere, he hit a still-respectable .282/.372/.501. In other words, Coors added 28 points of on-base percentage and 64 points of slugging percentage to his overall line.

Baseball-Reference.com has a statistic called AIR that indexes the combination of park and league offensive levels into one number to provide a measure of how favorable or unfavorable the conditions a player faced were. According to the site's definition, AIR "measures the offensive level of the leagues and parks the player played in relative to an all-time average of a .335 OBP and .400 Slugging Percentage. Over 100 indicates a favorable setting for hitters, under 100 a favorable setting for pitchers." Walker's AIR is the fifth-highest among players with at least 4,000 plate appearances, and all of the top five have a distinctly purple tinge to their careers:

Rank | Player | PA | AIR |

|---|---|---|---|

1T | Todd Helton | 9011 | 123 |

Neifi Perez | 5365 | 122 | |

3 | Vinny Castilla | 7305 | 120 |

4 | Dante Bichette | 6777 | 117 |

5T | Larry Walker | 7958 | 116 |

Earl Averill | 7160 | 116 | |

Ski Melillo | 5402 | 116 | |

Rip Radcliff | 4398 | 116 | |

9T | Jeff Cirillo | 6026 | 115 |

Joe Vosmik | 6007 | 115 | |

Odell Hale | 4057 | 115 |

Once you let the AIR out of Walker's hitting, he ranks 64th all-time in True Average at .309. That's certainly Cooperstown caliber in and of itself; he's right ahead of Hall of Famers Roberto Clemente at .304 and Wade Boggs at .302, for example. The problem is that those players had around 30 percent more plate appearances over the courses of their careers than Walker, who just couldn't stay on the field consistently enough. He topped 143 games just once (153 in 1997), and even excluding the strike years, averaged just 129 games a year from 1990 through 2003, before he really started to break down at age 37. In his seven best seasons according to True Average, he averaged just 125 games.

When I examined Walker's case last year using Baseball Prospectus' WARP as the underlying value measure for JAWS instead of Baseball-Reference's WAR, he was short of the standard for rightfielders, with 60.9 career WARP, 36.7 peak WARP and 48.8 JAWS, a shortfall of 4.8 points relative to the average Hall rightfielder's 66.2/40.9/53.6. Via the new methodology, he clears both the career and peak standards, and comes out 1.0 points above the JAWS standard, ninth among rightfielders.

Different replacement levels, methodologies for park adjustments and defensive systems all factor into the discrepancy to at least some extent. For example, Walker's monster 1997 season measures out at 9.6 WAR, including defense that's 10 runs above average according to Total Zone, the system used for seasons prior to 2003, when Defensive Runs Saved became available. That same '97 season measures out at 6.1 WARP, still a career high, albeit with defense that's 16 runs below average. BP's Fielding Runs Above Average puts Walker at −1 for his career, while Total Zone puts him at 95 runs above average, and Defensive Runs Saved at four runs above average for the 2003-2005 period, when he's at dead even in terms of TZ and −13 in terms of FRAA. When it comes to defense in particular, different inputs — batted ball data, for example — yield different answers.

Walker isn't the only candidate on this year's ballot whose standing improves via the switch from the old system to the new, or even the only one who rises above the standard at his position with the change. That shouldn't be incredibly alarming, however. In nine years of working with a system whose WARP base took several major evolutionary steps, the standings of some players — Alan Trammell comes to mind — changed over time. Players being elected to the Hall contributed to that as well.

My point is this: a change in the JAWS system's verdict is a consequence of our attempt to gain something resembling an objective answer to a question that may not have a truly objective answer. As with any process founded in science, we do the best we can with the tools at our disposal to provide answers to such questions, hopefully the right ones. Those answers may change as our tools develop and as new information becomes available.

Beyond the areas that JAWS covers, Walker's credentials are good but not exceptional; backed by WAR, his MVP award appears to be on solid ground, the batting titles less so. For 1997, Walker's .346 True Average is 23 points shy of that of Mike Piazza, who hit .362/.431/.638 while playing in parks that depressed scoring by five percent, compared to the ones that Walker played in that increased scoring by 21 percent. The Bill James Hall of Fame Standards and Hall of Fame Monitor stats, which dish out credit for things like seasons or careers with batting averages above .300, leagues led in key stats, and playoff appearances (Walker hit .230/.350/.510 in 121 postseason plate appearances, good but hardly exceptional), place Walker above the bar of the average Hall of Famer. Those metrics, though, weren't designed with Coors Field or the sustained scoring levels of the 1993-2009 period as a whole in mind. That alone is a big reason why JAWS came into being: I wanted a tool that could adjust accordingly.

Jay Jaffe is a contributing baseball writer for SI.com and the author of the upcoming book The Cooperstown Casebook on the Baseball Hall of Fame.