JAWS and the 2014 Hall of Fame ballot: Barry Bonds

Barry Bonds was a gifted -- and controversial -- star long before he was connected to steroids. (Ronald C. Modra/SI)

The following article is part of my ongoing look at the candidates on the BBWAA 2014 Hall of Fame ballot. Originally written for the 2013 election, it has been updated to reflect last year's voting results as well as additional research and changes in WAR. For a detailed introduction to JAWS, please see here. For the schedule and an explanation of how posts on holdover candidates will be presented, see here.

If Roger Clemens has a reasonable claim as the greatest pitcher of all time, then the same goes for Barry Bonds as a position player. Babe Ruth played in a time before integration, Ted Williams bridged the pre- and post-integration eras, and while both were dominant at the plate, neither was anything to write home about on the basepaths or in the field. Bonds' godfather, Willie Mays, was a big plus in both of those areas, but didn't dominate opposing pitchers to the same extent. Bonds used his blend of speed, power and surgical precision with regard to the strike zone to outdo them all, setting the single-season home run record with 73 in 2001 and the all-time home run record with 762 through 2007, reaching base more often than any player this side of Pete Rose and winning seven MVP awards along the way.

Despite his claim to greatness, Bonds may have inspired more fear and loathing than any ballplayer in modern history. Fear because opposing pitchers and managers simply refused to engage him at his peak, intentionally walking him a record 688 times -- once with the bases loaded -- and walking him a total of 2,558 times, also a record. Loathing because even as a young player, he rubbed teammates and media the wrong way and approached the game with a chip on his shoulder because of the way his father, three-time All-Star Bobby Bonds, had been driven from the game due to alcoholism.

As he aged, media and fans turned against Barry Bonds once evidence — most of it illegally leaked to the media by anonymous sources — mounted that he had used performance-enhancing drugs during the latter part of his career. With his name in the headlines more regarding his legal situation than his on-field exploits, his pursuit and eclipse of Hank Aaron's 33-year-old home run record turned into a joyless drag, and he disappeared from the majors soon afterward despite ranking among the game's most dangerous hitters even at age 43.

Bonds is hardly alone among the holdovers on this year's ballot who have links to PEDs. As with Clemens, the support he received during his first election cycle last year, 36.2 percent, was far short of election but significantly outdid that of Mark McGwire, Sammy Sosa and Rafael Palmeiro, either in their ballot debuts or since. The knocks against Bonds are similar to those players, but ultimately, he's in a class all by himself.

Player | Career | Peak | JAWS | H | HR | SB | AVG/OBP/SLG | OPS+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Barry Bonds | 162.5 | 72.8 | 117.7 | 2935 | 762 | 514 | .298/.444/.607 | 182 |

Avg HOF LF | 65.0 | 41.5 | 53.2 |

Like his father, Bonds was born in Riverside, Calif. He grew up further north, in San Carlos, and not surprisingly, excelled in baseball once he reached high school. The Giants chose him in the second round of the 1982 draft, the same year that his father's professional career ended with a brief stint for the Yankees' Triple-A team. The younger Bonds chose not to sign with the Giants and instead headed for Arizona State, where he earned All-American honors. He was drafted again after his junior year, this time by the Pirates as the sixth overall pick. B.J. Surhoff (Brewers), Will Clark (Giants), Bobby Witt (Rangers), Barry Larkin (Reds) and Kurt Brown (White Sox) were the five players chosen ahead of him. He tore up the A-level Carolina League that year, and then spent two months doing the same in the Triple-A Pacific Coast League in 1986 before being called up in late May. He made his major league debut on May 30, 1986, going 0-for-5 with three strikeouts and a walk against the Dodgers, though in August of that year, he appeared in the 17th inning of a suspended game that had begun on April 20, driving in the winning run in what now stands as his backdated "debut."

As a 21-year-old, Bonds hit just .223/.330/.416 for the Pirates in 1986 and struck out 102 times, the only season he would reach triple digits in that category. Batting leadoff most of the time, he did homer 16 times, steal 36 bases in 43 attempts, walk 65 times in 484 plate appearances and play above-average defense in centerfield en route a respectable showing good for 3.5 WAR. Shifting over to leftfield to accommodate the arrival of Andy Van Slyke in 1987, Bonds improved to 25 homers, 32 steals, 5.8 WAR and a .261/.329/.492 line. His plate discipline, and the respect accorded him by NL pitchers, leaped forward over the next two years; he drew 14 intentional walks among his 72 overall in 1988, and 22 out of 93 in '89, though he slumped to 19 homers and a .248 batting average in the latter year. That winter, the Pirates and Dodgers discussed a trade that would have sent third baseman Jeff Hamilton and reliever John Wetteland to Pittsburgh for Bonds.

Bonds broke out in 1990, earning All-Star and Gold Glove honors while hitting .301/.406/.565 with 33 homers (fourth in the league) and 52 steals (third). The 30-30 feat placed him in select company as one of 13 players to reach that dual milestone; his father had done so five times, while Mays was one of two other players to do so twice up to that point. His slugging percentage and his 9.7 WAR both led the league — the first of four straight years that he led in the latter category — and he won his first MVP award in a nearly-unanimous vote where one stray first-place ballot went to teammate Bobby Bonilla. The two killer BBs helped the Pirates go 95-67, winning the NL East for the first time since 1979, though they lost a six-game NLCS to the Reds.

Bonds helped Pittsburgh repeat as NL East champions in each of the next two seasons as well though the team succumbed to the Braves in seven-game NLCS both times. He led the NL with a .410 on-base percentage in 1991, and led in both on-base and slugging percentages in 1992 while hitting .311/.456/.624. For the first time, he also led the league in walks, with 127 (32 intentional); while it's tempting to attribute those latter totals to the departure of Bonilla for the Mets via free agency after the 1991 season, the reality is that manager Jim Leyland batted Bonilla fourth and Bonds fifth (!) for most of the former's final two years in Pittsburgh (Van Slyke hit third). After horrendous performances in his first two NLCS appearances, Bonds hit .261/.433/.435 with a homer and six walks in the 1992 series, but it wasn't enough. He did take home his second NL MVP trophy, avenging his loss to the Braves' Terry Pendleton the year before.

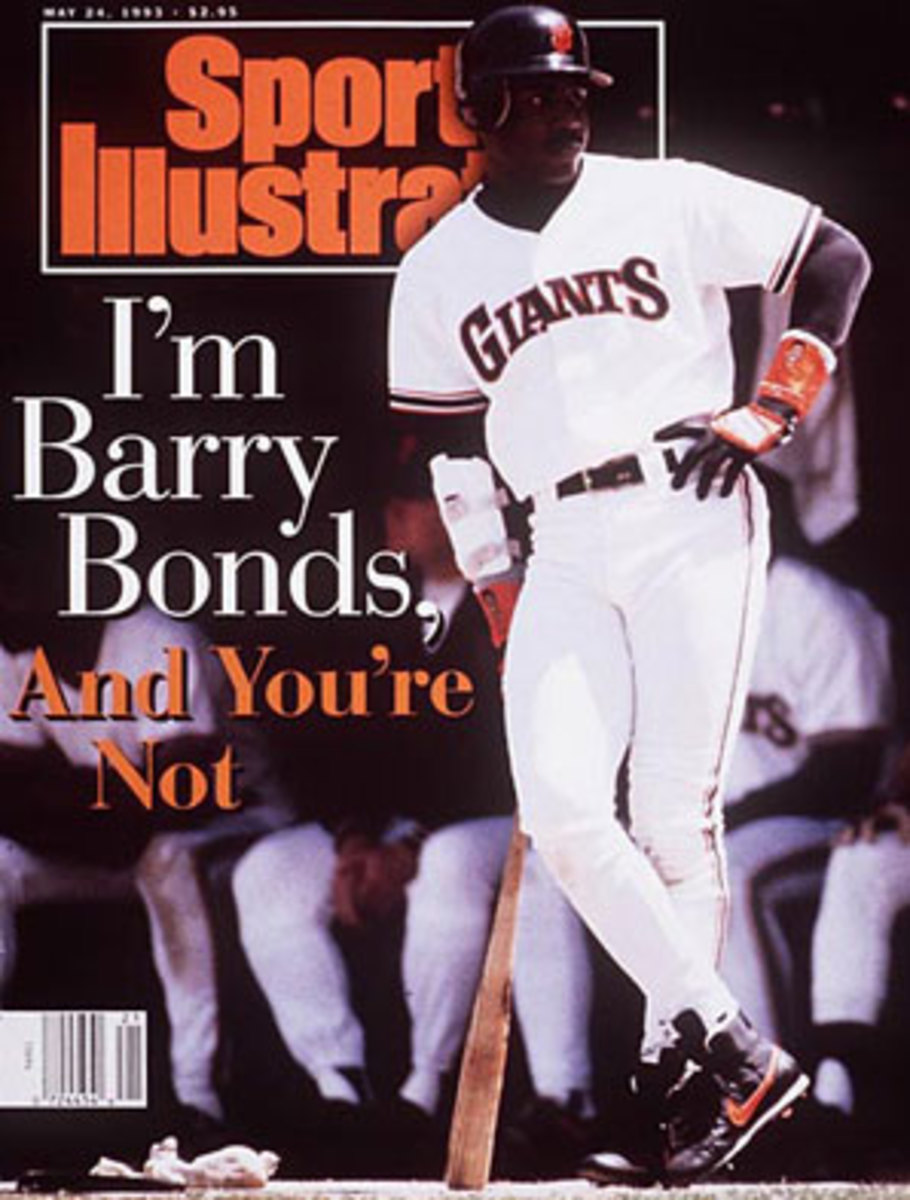

That was the end of Bonds' time in Pittsburgh. Now 28 years old, he signed a six-year, $43.75 million contract with the Giants, setting records for the largest deal ever (surpassing Cal Ripken's $32.5 million) and the highest average annual value (surpassing Ryne Sandberg's $7.22 million). Mays (his godfather) offered to unretire uniform number 24 for him to wear, but Bonds instead opted for the number 25 that his father wore as a Giant from 1968 through 1974. He lived up to his new contract with another MVP-winning season in 1993, hitting .336/.458/.677, leading the league in the latter two categories as well as homers (46), RBIs (123) and intentional walks (43). San Francisco won 103 games, but thanks to a pair of homers by Dodgers rookie Mike Piazza on the final day of the season, lost out to the 104-win Braves for the NL West flag.

Helped along by more league-leading walk totals, Bonds posted on-base percentages of .426 or more and slugging percentages of .577 or more in each of the next four years, averaging 38 homers a year in spite of the 1994-95 players' strike and leading the league in WAR in both 1995 and '96. Only in 1997 — the year second baseman Jeff Kent joined the team — did the Giants reach the playoffs, and they were swept by the Marlins in three games.

Bonds hit a fairly typical .303/.438/.609 with 37 homers, 28 steals and 130 walks in 1998, but his performance was lost amid the McGwire-Sosa home run chase. The story that later emerged from reporters Mark Fainaru-Wada and Lance Williams in their book Game of Shadows is that the attention accorded to those two sluggers led Bonds to take performance-enhancing drugs to keep up; after that season, he began training with Greg Anderson, a weightlifter and steroid dealer. Amid his intense training regimen, he tore a triceps tendon in his right elbow early in the 1999 season and needed surgery. Despite missing seven weeks, he still hit 34 homers (three fewer than the year before) in 102 games. He set a career-high with 49 homers in 2000 — second in the league, one short of Sosa's total — and hit .306/.440/.688, good for 7.7 WAR (third in the league). Playing their first year in Pac Bell Park, the Giants won the NL West but fell to the Mets in the Division Series. Bonds lost out on the MVP award to Kent, who hit .334/.424/.596 with 34 homers and 7.2 WAR, but drove in 125 runs, 19 more than his teammate.

With precise strike zone judgement, a swing that was more compact than ever and the ability to dig in at the plate enhanced by a bulky elbow guard, Bonds put up video game numbers in 2001: a .328/.515/.863 line with 73 homers and 177 walks; those last three numbers all set records. His sixth home run of the year, off the Dodgers' Terry Adams on April 17, made him the 17th player to reach 500 homers; it came in a flurry of six consecutive games with a home run. He matched that streak in May, this time hitting nine homers over a six-game stretch. At one point, he hit 38 homers during a 61-game stretch, a 101-homer pace if projected out to a full 162 games. His 71st blast of the year, off the Dodgers' Chan Ho Park on Oct. 5, 2001, broke McGwire's three-year-old record, but it — and his 72nd homer, also off Park — came in the same game in which the Giants were eliminated from postseason contention. Still, he became the first four-time MVP in baseball history and kicked off another stretch of four straight years leading the league in WAR, with 11.9.

Bonds never again reached 50 homers in a season, as managers grew increasingly wary of pitching to him. From 2002-04 he batted a combined .358/.575/.786 while averaging 45 homers and 193 walks per year, 83 of them intentional; in 2004, he drew an astounding 232 walks, 120 of them intentional, en route to a .609 on-base percentage, all records. He took home MVP honors in each of those years, running his total to seven.

On Aug. 9, 2002, he hit his 600th homer off the Pirates' Kip Wells, becoming just the fourth player to reach that plateau after Ruth, Mays and Aaron. He reached the World Series for the first time that year, and hit .471/.700/1.294 with four homers and 13 walks in a losing cause against the Angels. He passed Mays with his 661st homer off Milwaukee's Ben Ford on April 13, 2004, and hit number 700 off San Diego's Jake Peavy on Sept. 17. Even having turned 40 that year, it was apparent that Bonds still had enough ability to surpass Aaron's mark of 755 home runs.

By that point, he also had plenty of heat on him. In September 2003, Bonds' name surfaced as one of six major league players and 21 other athletes connected to the Bay Area Laboratory Co-Operative, which was at the center of a doping scandal involving previously undetectable steroids. In December 2003, Bonds testified in front of a grand jury that he had received "the Clear," and "the Cream," two such steroids, from Anderson during the 2003 season but had been told that they were flaxseed oil and a rubbing balm for arthritis. When confronted with documents — including lab test results, schedules of use and billing information — allegedly detailing his steroid regimen from 2001 through 2003, he claimed to have no knowledge that any substance he had ingested was illegal. All of this information was supposed to remain under court seal, but was leaked to the media illegally.

An entire cottage industry devoted to covering the BALCO scandal sprang up, and the case dragged on for years. Meanwhile, Major League Baseball began cracking down on performance-enhancing drug use by instituting testing and suspensions. Bonds' involvement in the BALCO case led the House of Representatives Government Reform Committee to omit him from their list of players and executives they called to testify in March 2005, in part because committee leaders feared his presence would overshadow the proceedings.

He had other problems by then. After undergoing a minor cleanup on his left knee in October 2004, Bonds had surgery on his right knee in January 2005, then suffered new tears in the menisci in that same knee, requiring yet another surgery on March 17, the same day as the hearings. He needed a third surgery in May to clean out an infection and didn't return to the Giants until Sept.12; he homered five times in 14 games, running his career total to 708. With routine days off incorporated into his schedule, he returned to regular action the following year, hitting .270/.454/.545 with 26 homers and a league-leading 115 walks in 130 games. During spring training, a lengthy excerpt from Game of Shadows was published in Sports Illustrated, detailing Bonds' steroid usage and relationship with BALCO, and dampening enthusiasm for the barrage of milestones that would follow. In that same issue, SI's Tom Verducci wrote:

Delivered with the blunt force of a sledgehammer, Game of Shadows is to Barry Bonds what the Dowd Report was to Pete Rose in 1989 -- it destroys the reputation of one of baseball's most accomplished players. Whether Bonds never hits another home run or hits 48 more, which would give him the most of all time, he never can be regarded with honor or full legitimacy. Shadows painstakingly catalogs him as a serial drug cheat, and thus the eye-popping stats that he has accrued stand all too literally as too good to be true.

Bonds soldiered on nonetheless. His May 28 homer off Colorado's Byung-Hyun Kim, the 715th of his career, pushed him past Ruth. He ended the year with 734 homers, and began his final push toward Aaron's total the following year. Number 755 came against the Padres' Clay Hensley in San Diego on Aug. 4, 2007, snapping a six-game homerless drought full of cut-ins to virtually every one of his plate appearances and landing him on the cover of SI. Number 756 came in San Francisco against Washington's Mike Bacsik on Aug. 7.

Bonds's 28 homers brought his career total to 762, and while he had hit .276/.480/.565 with another league-leading on-base percentage, the Giants decided that the 43-year-old free agent was too expensive and too much trouble to keep. Despite his desire to continue playing, the rest of the industry shunned him — perhaps colluding to do so — at least in part because the federal grand jury indicted him on charges of perjury and obstruction of justice in November 2007. Bonds pleaded not guilty in December. Flaws in the drafting of the indictment led to three more rounds of indictments and not-guilty pleas, the last of them in March 2011. His trial began on March 21 of that year, and he was found guilty on one count of obstruction of justice for giving an evasive answer when asked if Anderson had given him anything that required him to inject himself. The judge declared a mistrial on three remaining counts of making false statements to the grand jury.

The legal mess isn't over. Bonds' conviction was upheld by a federal appeals court in September 2013; he began serving his 30 days of house arrest and two years of probation even while continuing to appeal. Once that's done, he may file a grievance with the players' union regarding the end-of-career collusion. It's estimated that the government spent at least $50 million of taxpayer money to investigate BALCO via a prosecution whose misconduct with regard to due process and the right to privacy was far more odious than any of Bonds' sins.

That morass aside, Bonds' numbers make a case for him as the greatest position player of all time; he holds the records for homers and walks while ranking second in times on base (5,599) and extra-base hits (1,440), third in runs scored (2,227), fourth in RBIs (1,996) and total bases (5,976) and a still-impressive 33rd in steals (514). In addition to his seven MVP awards, he made 14 All-Star teams. Among batters with at least 8,000 plate appearances, his .444 on-base percentage ranks fourth all-time behind Williams, Ruth and Lou Gehrig, while his .607 slugging percentage ranks fifth behind Ruth, Williams, Gehrig and Jimmie Foxx. His 182 OPS+ ranks third behind Ruth (206) and Williams (190).

Thanks to his abilities on the basepaths and in the field, Bonds' 162.5 WAR is not only tops among leftfielders but higher than any player besides Ruth (163.2 as a hitter and another 20.6 as a pitcher), Cy Young (168.4) and Walter Johnson (165.6). Bonds' career WAR outdistances that of Williams, the second-ranked leftfielder, by a whopping 39.3 wins, while his 72.8 peak WAR outdoes the Splendid Splinter by 3.5 wins, half a win per year.

The extent to which Bonds' numbers owe something to PED use is unknowable, but whether he'll get into the Hall of Fame has more to do with how the voters view his relationship to the drugs. In the eyes of many voters, Bonds and every other PED user is a cheater, beyond redemption in the context of recognizing the game's greats. As I outlined last year in this series and at greater length in the book Extra Innings, I disagree with that mindset. Instead, I believe that voters should distinguish between PED use that came during baseball's "Wild West" era — when it took a complete institutional failure on the part of the players' union, team owners, the commissioner, the media and fans to prevent a coherent drug policy from being implemented — and use that came after testing began and penalties were imposed.

From what we know, Bonds' usage occurred in the context of so many other dopers, pitchers as well as hitters. He is a none-too-flattering reflection of the era in which he played. Even so, he's no Lance Armstrong or Ryan Braun, men who intimidated or smeared those who gave evidence against them, nor is he Alex Rodriguez, who... we're trying to keep this shorter than a novella, right?

If one wants to play the "He was a Hall of Famer before he touched the stuff" game as I did with Clemens, considering only what Bonds did through 1998, his 411 homers, 1,917 hits, 445 steals and .290/.411/.556 line were good for 99.6 career WAR (which would rank third among leftfielders), 62.5 peak WAR (second) and 81.1 JAWS (third behind Williams and Rickey Henderson). Bottom line: warts and all, he gets the nod here.

Bonds didn't come close to getting in on the first ballot last year. Eight other players — including first-timers Craig Biggio, Mike Piazza, Roger Clemens and Curt Schilling — received a higher share of the vote than his 36.2 percent. What I wrote for the Clemens and Schilling pieces in this series applies here:

Since the BBWAA returned to voting annually for the Hall of Fame, 16 players have debuted on the ballot with between 25 and 45 percent of the vote (here I'm including Andre Dawson at 45.3 percent). Eight were eventually elected by the writers, one by the Veterans Committee, with the fates of four (Jeff Bagwell, Edgar Martinez, Don Mattingly and Lee Smith) hanging in the balance as they remain eligible. Of the eight who made it via the BBWAA, the average wait was 6.8 more years, ranging from Early Wynn (three more years) to Jim Rice (14 more years), with the latter the only player to exceed eight more years. Five of those eight debuted with lower shares of the vote than Schilling [and Clemens and Bonds]: Goose Gossage (33.3 percent), Eddie Mathews (32.3 percent), Rice (29.8 percent), Wynn (27.9 percent) and Luis Aparicio (27.8 percent); their average wait was also 6.8 more years.