JAWS and the 2015 Hall of Fame ballot: Curt Schilling

The following article is part of my ongoing look at the candidates on the BBWAA 2015 Hall of Fame ballot. Originally written for the 2014 election, it has been updated to reflect recent voting results as well as additional research and changes in WAR. For a detailed introduction to this year's ballot, please see here. For an introduction to JAWS, see here.

Curt Schilling was at his best when the spotlight was brightest. A top starter on four pennant winners and three World Series champions, he has a strong claim as the best postseason pitcher of his generation. His case for Cooperstown is backed by a track record of dominance during the regular season as well, though he never won a Cy Young award, and he finished with "only" 216 regular season wins. That’s a problem given that seven of the eight starters elected since 1992 have had at least 300 wins. The electorate may be poised for change, but Schilling won’t be its vanguard.

Schilling was something of a late bloomer who didn't click until his age-25 season, after he had been traded three times. He spent much of his peak pitching in the shadows of even more famous (and popular) teammates, which may have helped to explain his outspokenness. Whether expounding about politics, performance-enhancing drugs, the QuesTec pitch-tracking system or a cornerstone of his legend, he wasn't shy about telling the world what he thought, earning the nickname "Red Light Curt" from Phillies manager Jim Fregosi. Even with his career long since finished, he remains a controversial and polarizing figure.

JAWS and the 2015 Hall of Fame ballot: Schedule for write-ups

In an ideal world, Schilling would sail into Cooperstown without a fuss. However, he debuted with an underwhelming 38.8 percent of the vote in 2013, and slipped to 29.2 percent in 2014, as the ballot became even more crowded with pitchers, a crowd that hasn’t abated with the arrivals of Randy Johnson, Pedro Martinez and John Smoltz on this ballot. He's still got time to gain entry, but as with last year, he’ll spend another cycle with his credentials overshadowed by pitchers with more wins and/or Cy Young awards. Even so, his candidacy deserves a close look.

pitcher | career | peak | jaws | w | l | era | era+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Curt Schilling | 79.9 | 49.0 | 64.5 | 216 | 146 | 3.46 | 127 |

Avg. HOF SP | 73.4 | 50.2 | 61.8 |

|

|

|

|

Born in Anchorage, Alaska, in 1966, the son of a career Army man, Schilling was part of a family that bounced around the U.S. before settling in Phoenix. Undrafted out of high school, he attended Yavapai Junior College in Arizona and wasn't drafted until January 1986, when he was chosen in the second round by the Red Sox. He put himself on the prospect map by leading the A-level South Atlantic League in strikeouts in 1987, his second professional season at age 20, but midway through the next year he was traded to the Orioles along with Brady Anderson in a deadline deal for pitcher Mike Boddicker. He debuted in the majors in September 1988, making four starts but getting rocked for a 9.82 ERA, and he was knocked around during a similar cup-of-coffee the following year.

JAWS and the 2015 Hall of Fame ballot: Randy Johnson

Schilling stuck around as a reliever for about half of the 1990 season, putting up a 2.54 ERA in 46 innings, but he didn't exactly impress Orioles manager Frank Robinson upon arrival. Recounted the pitcher in a 1998 Sports Illustrated profile, "I walk in, I got the earring and half my head shaved, a blue streak dyed in it. He says, 'Sit down,' and then just cocks his head and stares at me for a while. Finally, he says, 'What's wrong with you, son?' I just sit there and act dumb and say, 'Huh? What do you mean?'"

Schilling lost the earring and the blue streak, but his lack of maturity persisted. Summoned from the bullpen in September of '90, he admitted to not knowing who he was facing, an incident that spelled the end of his time in Baltimore. That winter, the Orioles sent him to Houston (along with Steve Finley and Pete Harnisch) for Glenn Davis, a deal that's still reviled in Baltimore.

Schilling was no big hit in Houston, either. After spending the 1991 season in the bullpen, he was traded to Philadelphia for Jason Grimsley just before Opening Day the following year. Six weeks into the season, he finally got another shot to start, and he was outstanding, completing 10 of 26 turns with four shutouts, finishing the season 14-11 with a 2.35 ERA in 226 1/3 innings. His ERA and 5.9 WAR both ranked fourth in the league.

Schilling's ERA ballooned to 4.02 (99 ERA+) in 1993 as a full-time member of the rotation, but his 186 strikeouts ranked fourth in the league. More importantly, he helped Philadelphia win its first division title in a decade. He then earned NLCS MVP honors against Atlanta with two strong, eight-inning starts in which he allowed a combined three earned runs and struck out 19, though he received no-decisions in both. Roughed up in the World Series opener against the Blue Jays, Schilling rebounded to throw a five-hit shutout in Game 5 to stave off elimination, though Toronto won the series on Joe Carter's walk-off homer in Game 6 nonetheless.

Injuries — including surgery for a torn labrum in 1995 — and the players' strike limited Schilling to just 56 starts over the next three years, but he returned from his surgery with improved velocity, and continued to miss bats. He whiffed 182 batters in 183 1/3 innings in 1996, reaching double digits in seven of his final 11 starts, and though he made just 26 starts overall, his eight complete games led the league. Both his 3.19 ERA and his 4.9 WAR cracked the top 10.

JAWS and the 2015 Hall of Fame ballot: Roger Clemens

Despite the fact that the Phillies had suffered three straight losing seasons, including a 95-loss campaign in 1996, Schilling chose to sign a below-market, three-year, $15.45 million extension with Philadelphia in April 1997. While the team was again hapless that year, finishing 68-94, he was anything but, going 17-11 with a 2.97 ERA (143 ERA+) in 254 1/3 innings and a league-leading 319 strikeouts — the highest total in the majors since Nolan Ryan's 341 in 1977 and the most in the NL since Sandy Koufax's 382 in 1965. He made his first All-Star team and placed fourth both in WAR (6.3) and in the Cy Young voting, losing out to the Expos' Pedro Martinez, who struck out 305 with a 1.90 ERA.

The next year, Schilling became the first pitcher since J.R. Richard in 1978 and '79 to notch at least 300 strikeouts in back-to-back seasons; he finished with an even 300, good enough to lead the league, and his 268 2/3 innings and 15 complete games — still the highest total since 1992 — paced the circuit as well. His 6.2 WAR again ranked fourth.

The mileage soon caught up to Schilling. Though he earned All-Star honors for the third straight year in 1999 — and starting the game for the NL squad — he made just three starts after July 23 due to shoulder inflammation, and after undergoing offseason surgery didn't make another regular season appearance until April 30 of the following year. Though not as dominant as in 1997 and '98, he pitched reasonably well; with the Phillies en route to a 97-loss season, he agreed to waive his no-trade clause and was sent to Arizona for a four-player package on July 26, 2000. The Diamondbacks were tied for first place in the NL West at the time of the trade, but ultimately fell short of a playoff spot.

With Schilling paired with lefty Randy Johnson to form the league's best one-two punch, Arizona won the division in 2001. Schilling set career highs with 22 wins and 8.8 WAR and struck out 293 hitters in 256 2/3 innings while walking just 37 for an eye-popping 7.5 strikeout-to-walk ratio. He would have waltzed home with the Cy Young award had Johnson not struck out 372 and won 21 games himself en route to the second of four straight Cys. Schilling placed second in the voting.

He sparkled in the postseason, throwing three complete game victories in the first two rounds of the playoffs against the Cardinals and Braves, striking out 30 while allowing just three runs. In the World Series against a Yankees team seeking its fourth straight championship, he yielded one run in seven innings in a winning effort in Game 1. He duplicated that performance on three days' rest in Game 4, but Diamondbacks closer Byun-Hyung Kim allowed a two-run homer by Tino Martinez in the ninth and then Derek Jeter’s's walkoff solo shot in the 10th.

JAWS and the 2015 Hall of Fame ballot: Mike Mussina

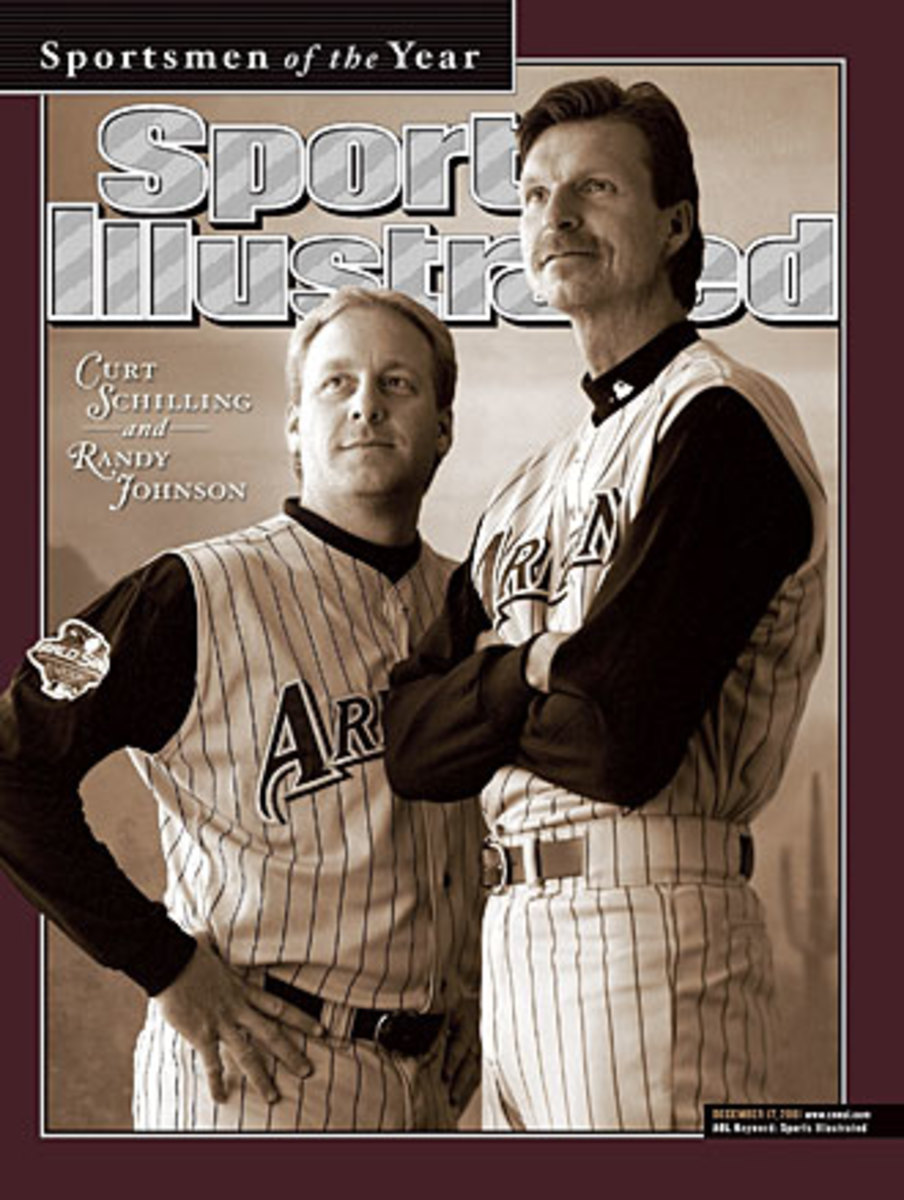

The series wound up stretching to seven games, and Schilling again took the ball on three days' rest. He shut New York down for the first six innings, but departed in the eighth, trailing 2-1 after surrendering a homer to Alfonso Soriano. Johnson came out of the bullpen in relief, and Arizona rallied for two runs in the bottom of the ninth inning against Mariano Rivera. The Diamondbacks were champions. Schilling shared co-MVP honors with Johnson (and soon enough, Sports Illustrated’s Sportsmen of the Year honors as well). For the postseason, he had put up a 1.12 ERA in a record 48 1/3 innings (broken by Madison Bumgarner this year), with 56 strikeouts (still a record) and just six walks.

Schilling placed second to Johnson in the Cy Young voting again the following year, an 8.3 WAR campaign in which he won 23 games and struck out 316 batters while walking just 33, for a 9.6 strikeout-to-walk ratio; he led the league in that latter category for the second straight year and would go on to do so five times in a six-year span from 2001-06.

In 2003 he was limited to 24 starts by appendicitis and two fractured metacarpals, the result of a pair of comeback shots in the same game. That was his last year in Arizona. After the season, he waived his no-trade clause for a trade to the Red Sox, who had come agonizingly close to their first AL pennant since 1986, only to lose to the Yankees via Aaron Boone's walkoff home run in Game 7 of the ALCS. As part of the trade, Schilling signed a three-year, $37.5 million extension with a $13 million vesting option contingent on the Sox winning the World Series, something that hadn't happened since 1918 (the clause actually ran afoul of MLB’s contract rules).

Pairing with Martinez as Boston's co-ace, Schilling put up another banner season, with 21 wins, a 3.26 ERA (148 ERA+, despite pitching home games at in hitter-friendly Fenway Park) and 203 strikeouts. He earned All-Star honors for the sixth time, but was hampered by a tendon problem in his right ankle as the postseason came around. After an unexceptional start against the Angels in the Division Series, he was chased by the Yankees after just three innings in Game 1 of the ALCS. It didn't appear as though the injury would matter once New York built a 3--games-to-0 lead, but when the Sox clawed their way back into the series, Schilling took the ball for Game 6 in the Bronx.

The day before the start, doctors performed an experimental procedure to secure a tendon in place using three stitches. TV shots that night routinely captured the blood in Schilling's ankle seeping through his sock. Nevertheless, his body held together long enough for him to turn in a seven-inning, one-run performance, helping the Sox force a Game 7, which Boston won handily. He threw six innings of one-run ball against the Cardinals in Game 2 of the World Series, helping the Red Sox to their first world championship in 86 years.

Despite offseason surgery, Schilling's ankle continued to trouble him well into the following year. Splitting his time between the rotation and closing — something he'd done regularly only in early 1991 — he finished with an ugly 5.69 ERA in just 93 1/3 innings. He rebounded to throw 204 innings of 3.97 ERA (120 ERA+) ball in 2006, striking out 183 and finishing with a stellar 6.5 strikeout-to-walk ratio, but Boston missed the playoffs.

JAWS and the 2015 Hall of Fame ballot: Jeff Bagwell

Schilling got out to a strong start the following year, but his season unraveled after he fell one out shy of no-hitting the A's on June 7, and he lost six weeks to shoulder inflammation. He mustered some semblance of his old form in the postseason, though. He threw seven shutout innings in the Division Series clincher against the Angels, then rebounded from an ALCS Game 2 pounding by the Indians to yield two runs over seven innings in Game 6 and wobbled through 5 1/3 innings in Game 2 of the World Series against the Rockies — another sweep, as it turned out.

Schilling signed an incentive-laden one-year, $8 million deal to return to Boston in 2008, but further shoulder problems that winter led to a public battle with the Red Sox over his treatment; he didn't undergo surgery to repair his biceps tendon and labrum until June, and never made it into a game. The following spring, he announced his retirement.

Schilling finished his career with 216 wins, a lower total than all but 15 of the 59 starting pitchers in the Hall of Fame, only two of whom — Koufax and Don Drysdale — pitched in the majors during the post-1960 Expansion Era. The BBWAA voters have taken a long time to come around to the idea that pitcher wins aren't the ideal measure of success in a modern era where it's been shown that offensive, defensive and bullpen support are major factors in the compilation of those precious Ws. After electing Ferguson Jenkins in 1991, it took 20 years — until Bert Blylelven in 2011 — for another starter with fewer than 300 wins to be elected by the writers. Given that it took the writers 14 years to elect Blyleven (287 wins), and that Jack Morris (254) nearly was elected before falling off the ballot last year, it’s not yet clear that a majority of voters can distinguish between the cases of those two pitchers, the former’s founded on dominance and run prevention, the latter’s based more on stamina and old-school win totals.

Schilling was the first among a wave of non-300 win pitchers to hit the ballot, followed by Mussina (270 wins) in 2014 and Martinez (219) and Smoltz (210) this year. Pitching in the highest scoring era since the 1930s, those men more than held their own against lineups much deeper than their predecessors faced, working deep into counts to rack up high strikeout totals before yielding to increasingly specialized bullpens. The shape of their accomplishments may be different than the even larger cohort of pitchers from the 1960s and '70s who helped set that 300-or-bust standard, but they belong alongside them in Cooperstown just the same. Martinez and Smoltz will likely gain entry either this year or in the near future, which should open things up, not only for Schilling but also Mussina and future candidates such as Roy Halladay (203 wins).

Even so, Schilling's candidacy has far more than wins going for it. In the postseason he was 11-2 with a 2.23 ERA in 133 1/3 innings covering 19 starts, helping his teams to four pennants and three championships; in the World Series alone, he was 4-1 with a 2.06 ERA in seven starts totaling 48 innings. Other pitchers of his era racked up more appearances and wins, but no starter from the post-1960 Expansion Era with at least 100 postseason innings had as low an ERA. Among pitchers from that era with at least 40 innings in the World Series, only Koufax (0.94) and Bob Gibson (1.89) have lower ERAs; both pitched at a time when scoring levels were much lower, making Schilling's accomplishments all the more impressive.

Turning back to the regular season, Schilling's 3,116 strikeouts rank 15th all-time, while his 8.6 strikeouts per nine ranks third among pitchers with at least 3,000 innings, behind only Johnson and Ryan and just ahead of Roger Clemens. It's true that Schilling pitched in an era where strikeout rates were almost continually on the rise, but he was still ahead of the curve; his trio of 300-K seasons puts him in the company of Johnson, Ryan and Koufax as the only pitchers with more than two such seasons during the Expansion Era. Eight times he finished in his league's top five in strikeouts. What's more, he managed impeccable control while doing so, leading the league in strikeout-to-walk ratio five times and placing in the top five another four times; his 4.4 ratio is the highest of any post-19th century pitcher.

Schilling never won a Cy Young award, but he placed second three times from 2001-04. Because he's all over the leaderboard in key pitching categories, he scores very well in Bill James' Hall of Fame Monitor metric, which gives credit for awards, league leads, postseason performance and so on; on a scale where 100 indicates "a good possibility" of making the Hall of Fame and 130 indicates "a virtual cinch," his 171 points clears the bar by a mile.

JAWS and the 2015 Hall of Fame ballot: Craig Biggio

Schilling's ability to miss bats and prevent runs enabled him to finished in his league's top five in WAR eight times and to rack up nine seasons of at least 5.0 WAR; among his contemporaries, only Clemens (14), Johnson (11), Maddux (11) and Mussina (10) had more, while Martinez had as many. His 79.9 career WAR ranks 26th all-time, 6.5 wins above the standard for Hall of Fame starters. His peak score of 46.7 WAR is 1.2 wins below the standard — a couple runs per year, spread out over seven seasons. His overall JAWS, however, is 2.7 ahead of the standard, good for 27th all-time, ahead of five 300-game winners (Glavine, Ryan, Mickey Welch, Don Sutton and Early Wynn) as well as 32 other enshrined starters. That's a Hall of Fame pitcher.

Since the BBWAA returned to voting annually for the Hall of Fame in 1966, 18 players have debuted on the ballot with between 25 and 45 percent of the vote (including Andre Dawson, who got 45.3 percent). Eight were eventually elected by the writers and one by the Veterans Committee, with the fates of six (Jeff Bagwell, Roger Clemens, Edgar Martinez, Don Mattingly, Schilling and Lee Smith) still hanging in the balance. Of the eight BBWAA honorees, the average wait was 6.8 more years, ranging from Wynn (three more years) to Jim Rice (14 more years), with the latter the only player to exceed eight more years. Five of those eight debuted with lower shares of the vote than Schilling: Goose Gossage (33.3 percent), Eddie Mathews (32.3 percent), Rice (29.8 percent), Wynn (27.9 percent) and Luis Aparicio (27.8 percent); their average wait was also 6.8 more years.

Meanwhile, 12 candidates received between 25 and 35 percent of the vote in their second year of eligibility (again stretching, this time to include Rice at 35.3 percent). Five eventually gained entry via the writers (Rice, Aparicio, Gary Carter, Don Drysdale and Bruce Sutter), with an average wait of 7.8 more years, ranging from four (Carter and Aparicio) to 13 (Rice). Three others had to wait for the Veterans Committee.

Given the suddenly truncated eligibility period, an additional 7.8 years would take Schilling to his 10th and final ballot. While I doubt he’ll have to wait quite that long, his never-ending gift for controversy could provide an excuse for a voter here or there to leave him off a ballot so long as the field remains overcrowded. Even if that’s not a factor, it’s clear that the crowd will have to thin before he can make headway toward the plaque in Cooperstown that is his due.