Hurting Harper among Nationals' concerns, but Washington still a threat to Cubs

Can the Nationals to be trusted in October? On paper, they are the team with the best shot at derailing the freight train that is the Cubs, provided both clubs survive the National League Division Series. Their steady play has been admirable: Washington has held first place in the NL East for all but four days this season, all of them before May 13.

But the Nationals have concerns as they close in on a third division title in five years. They don't have a healthy Stephen Strasburg or Bryce Harper. Their only lefthanded starter, Gio Gonzalez—who looms as their most important pitcher in a Division Series matchup against the lefty-averse Dodgers—remains an enigma. Their closer, Mark Melancon—who has received a heavy workload since Washington acquired him from Pittsburgh on July 30 (he pitched in 23 of his first 40 games with the team)—has been asked to protect one postseason lead in his career, which he blew.

Remember, we’re talking about an organization that has won one playoff series in its 48 years (as the Montreal Expos in the 1981 NLDS) and infamously blew ninth-inning leads en route to first-round ousters in 2012 and '14. We’re not talking about Billy Goat curses yet, but this franchise is working on its own half-century tradition of bad karma.

Had Washington entered October with Strasburg and Max Scherzer available to start 11 postseason games across three rounds, its power pitching would give it an excellent chance against any opponent. Strasburg has always received kid-glove treatment, and now he's hurt again as he deals with a strained flexor mass in his right elbow. After taking 10 days off, he played catch for five minutes last Saturday; that's a long way from getting anywhere close to throwing a bullpen session, never mind cranking it up for a postseason start.

Scherzer, meanwhile, is healthy but he has never started on three days of rest following a previous start. When I asked him about doing so this postseason, he didn’t sound eager for it. “That’s asking a lot,” he said. “You’re trained to give everything you have every fifth day. You might be able to get through it, but where it would really show up is your next start.”

It’s difficult to know just how good the Nationals are. They coasted through the regular season in part because of a hale Strasburg (they went 19–5 in his 24 starts) and because they absolutely pummeled intra-division weaklings Atlanta and Philadelphia (they went 29–9 against those two teams and are 58–53 against everyone else). You likely will not be seeing Strasburg and you will definitely not see the Braves and Phillies in the postseason. Washington is a combined 3–8 against the Cubs and Dodgers.

"We have good pitching, pretty good defense and we hit the ball out of the ballpark," manager Dusty Baker said when asked what he likes about his team. "We have the second-best record in baseball. We still have too many strikeouts to my liking. We turn double plays. And that’s what I like to look at—how we match up in areas against our opponents ... double plays turned versus double plays we hit into [+28], strikeouts versus strikeouts [-227], walks versus walks [+69].... We’re second in defense, second in pitching, in the middle in batting average and the upper third in runs. We do quite a few things well."

Even Baker knows, however, that his team isn’t quite ready for October. The offense is vulnerable because teams can attack Harper and Ryan Zimmerman, even with runners on base.

Asked about Harper’s struggles, Baker said, "He’ll figure it out. He won’t admit it, but his balance is off. I need him and Zim. Those two guys are the key if we’re going to be operating on all cylinders. Zim’s a carrier. There are helpers and there are carriers. Carriers can carry you for two weeks to two months. Helpers fill in here and there. Zim’s a carrier. I need those two guys."

Asking Zimmerman to be a carrier may be asking too much for a guy who has been struggling for four months. Since May 5, Zimmerman is hitting .202/.253/.362. Injuries and age (he turns 32 next week) are conspiring against someone with a high-maintenance, timing-dependent swing.

Harper is likely to fall into a hot streak, but that’s only if his troublesome upper right shoulder/neck issue improves and allows him unrestricted passes at the baseball. Go back and look at an at-bat he had against the Giants' Matt Cain on Aug. 6. Harper fouled off a 2–2 pitch and doubled over in pain. By then the injury had already plagued him for about a month. He has played through the discomfort.

"At one point he could barely throw the ball 40 feet," said one source close to Harper. Over the weekend, Harper played so curiously shallow in rightfield that Baker had to ask him about it. (Baker kept Harper's answer private.)

The Nationals and Harper have been tight-lipped about his condition. But last Saturday, Baker admitted to me “the shoulder thing” has bothered the reigning NL MVP. He’s simply not the same hitter, and you can see it clearly the way pitchers consistently beat him on fastballs away.

I went back and looked at all fastballs thrown to Harper this year and last year in the same area: belt high and above, outer third of the zone and farther away. The contrast is striking.

Year | Avg (Hits/At-bats) | Home Runs |

|---|---|---|

2015 | .329 (24 for 73) | 9 |

2016 | .203 (11 for 54) | 3 |

Harper, perhaps compensating for the front shoulder on pitches that require extension, is often off-balance on fastballs away. He spins on his right ankle and drifts away from the pitch as he swings through the zone, often causing him to fall toward the third-base dugout, like a pitcher falling off the side of the mound after release. Baker gave Harper a “mental day off” Monday in Miami—the manager noticed a decline in his concentration—though Harper did pinch hit in the ninth inning. He popped out on a fastball away.

Since Aug. 29, Harper is hitting .164/.307/.262 with one home run in 61 at-bats. He’s still taking his walks and showing tremendous plate discipline, but he’s not nearly as aggressive when he needs to be (he’s looked at more strikes and swung less often overall than ever before in his career) and the ball is not jumping off his bat consistently.

Harper simply isn’t hitting the ball as hard as last year, or even as hard as he did in the first half of the season. Compared to the same date last year, Harper has hit 23% fewer balls with an exit velocity of 100 mph or more. When you look at those hard-hit balls month by month, you can see the physical attrition during the past three months. Harper’s hard-hit balls—those with an exit velocity of 100 mph or more—from April to June were nearly identical this year compared to 2015 (54 vs. 56). But from July through Sept. 19, he has suffered a noticeable dropoff (35 vs. 60).

This list reveals the month-by-month consistency of Harper’s hitting last year and the decline of it this year.

MOnth | 2016 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|

April | 20 | 13 |

May | 12 | 21 |

June | 22 | 22 |

July | 14 | 21 |

August | 16 | 24 |

September | 5 | 23 |

Total | 89 | 124 |

As for Gonzalez, the veteran lefthander with premium stuff continues to be held back by a lack of consistent focus. A clunker of an outing against Atlanta last Saturday broke some of the momentum he had gained in recent starts. Gonzalez still has trouble holding the other team in the half inning after Washington scores, and he is the worst starting pitcher in the league with runners in scoring position (.336)—typical traits of a young pitcher, not someone in his ninth season. Gonzalez has made three postseason starts and never made it past the fifth inning, walking 12 batters in 14 innings.

Longest World Series Championship Droughts

Cleveland Indians last won in 1948

Pictured: Bob Lemon

Texas Rangers/Washington Senators never won, Est. 1961

Pictured: Joe Hicks

Houston Astros/Colt .45's never won, Est. 1962

Pictured: Norm Larker

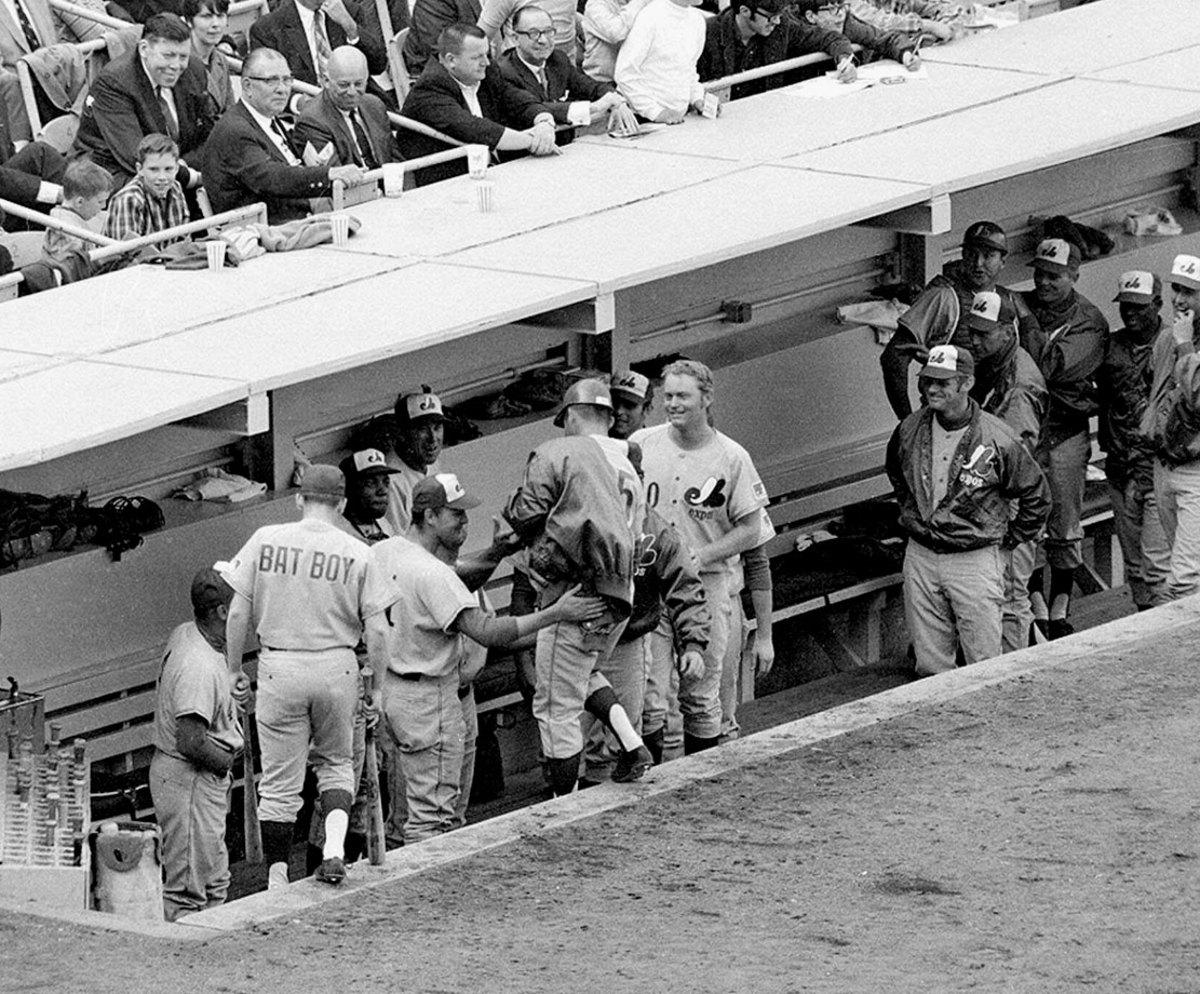

Washington Nationals/Montreal Expos never won, Est. 1969

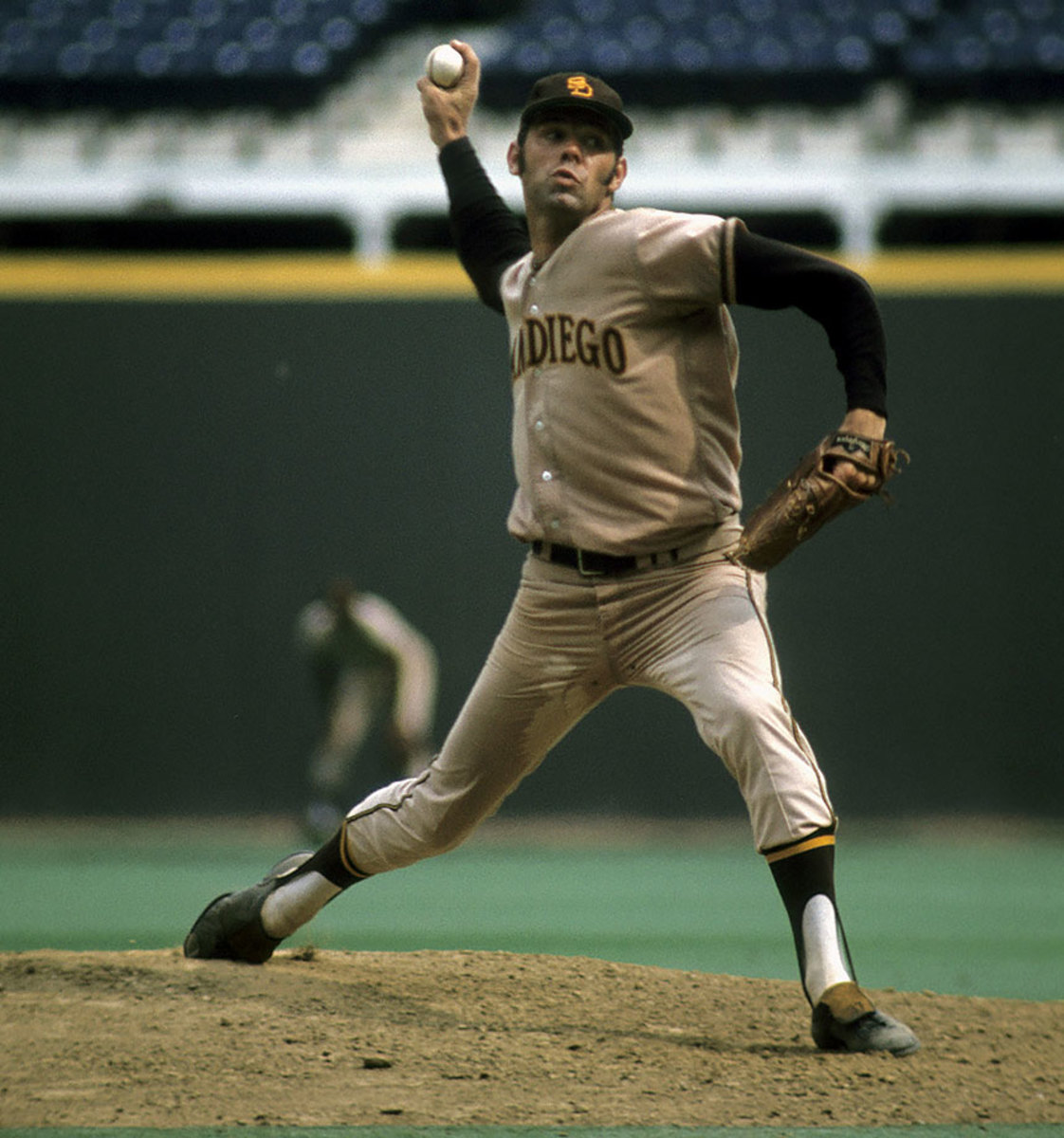

San Diego Padres never won, Est. 1969

Pictured: Clay Kirby

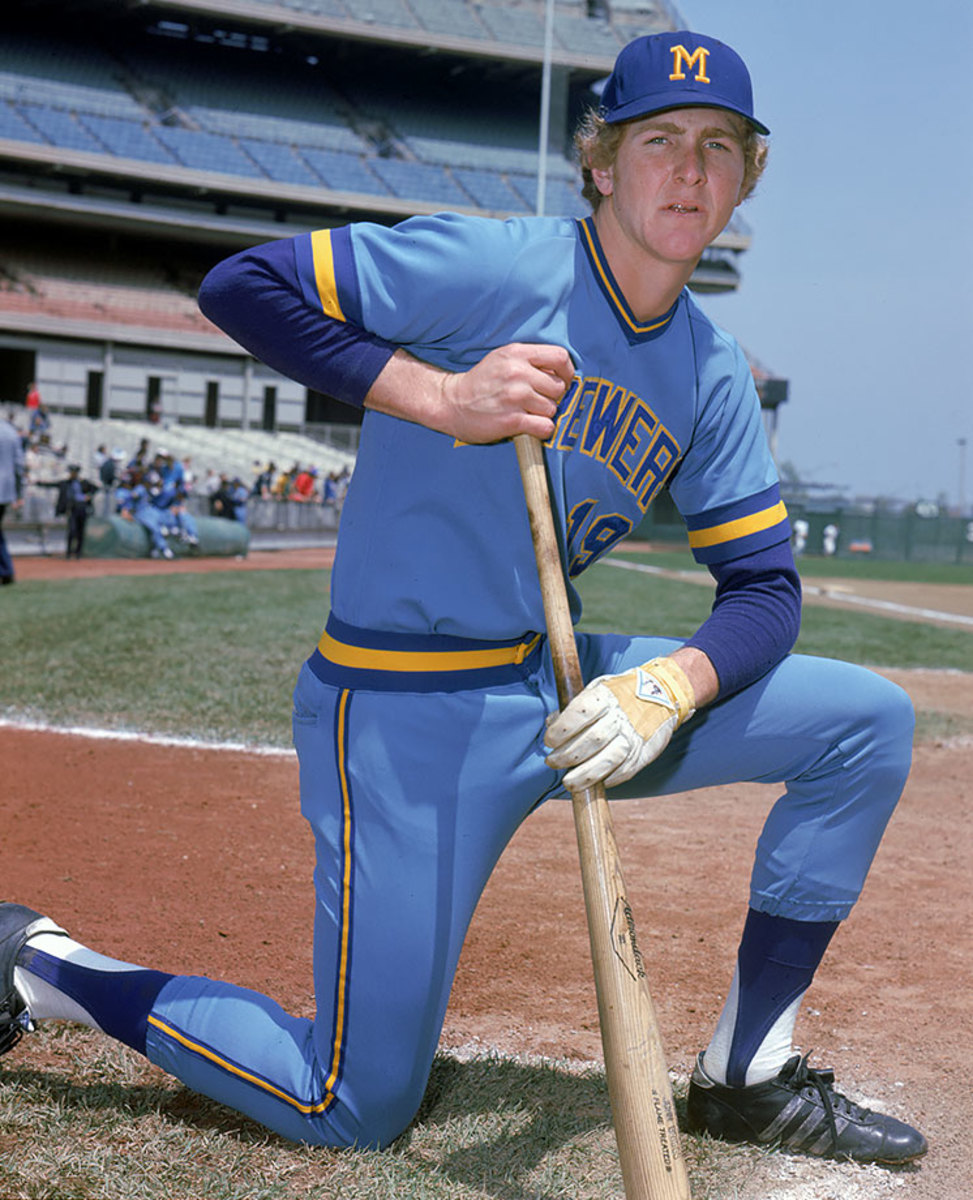

Milwaukee Brewers/Seattle Pilots never won, Est. 1969

Pictured: Robin Yount

Seattle Mariners never won, Est. 1977

Pictured: Part-owner Danny Kaye

Pittsburgh Pirates last won in 1979

Pictured: Willie Stargell and Manny Sanguillen

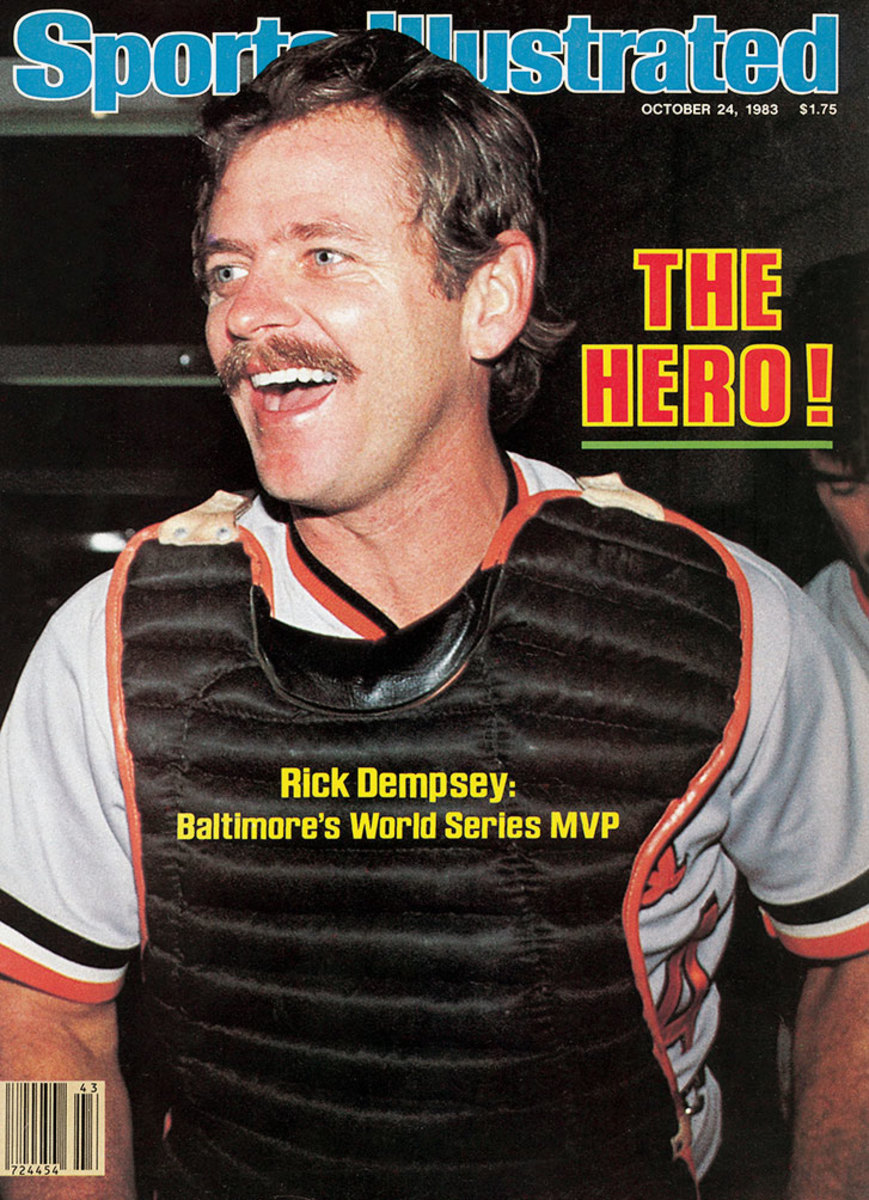

Baltimore Orioles last won in 1983

Pictured: Rick Dempsey

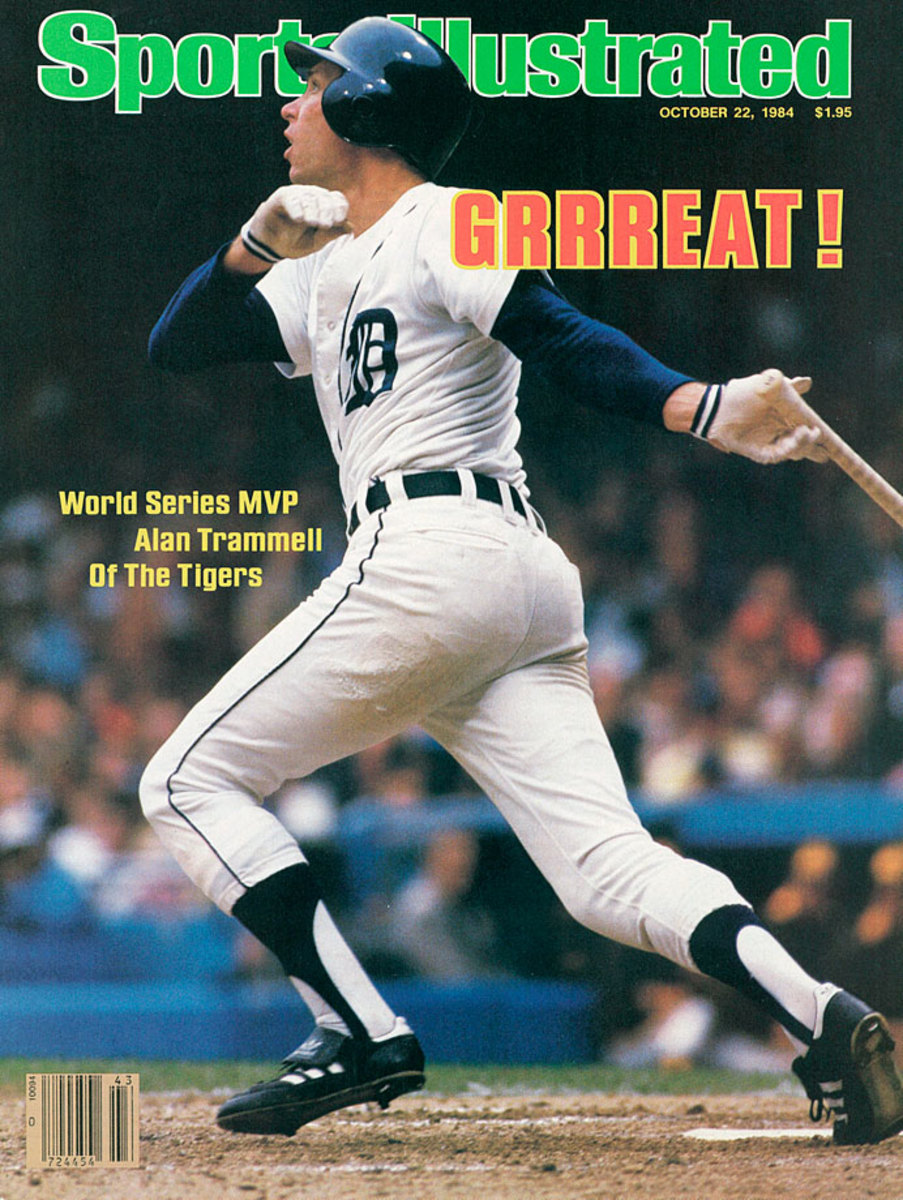

Detroit Tigers last won in 1984

Pictured: Alan Trammell

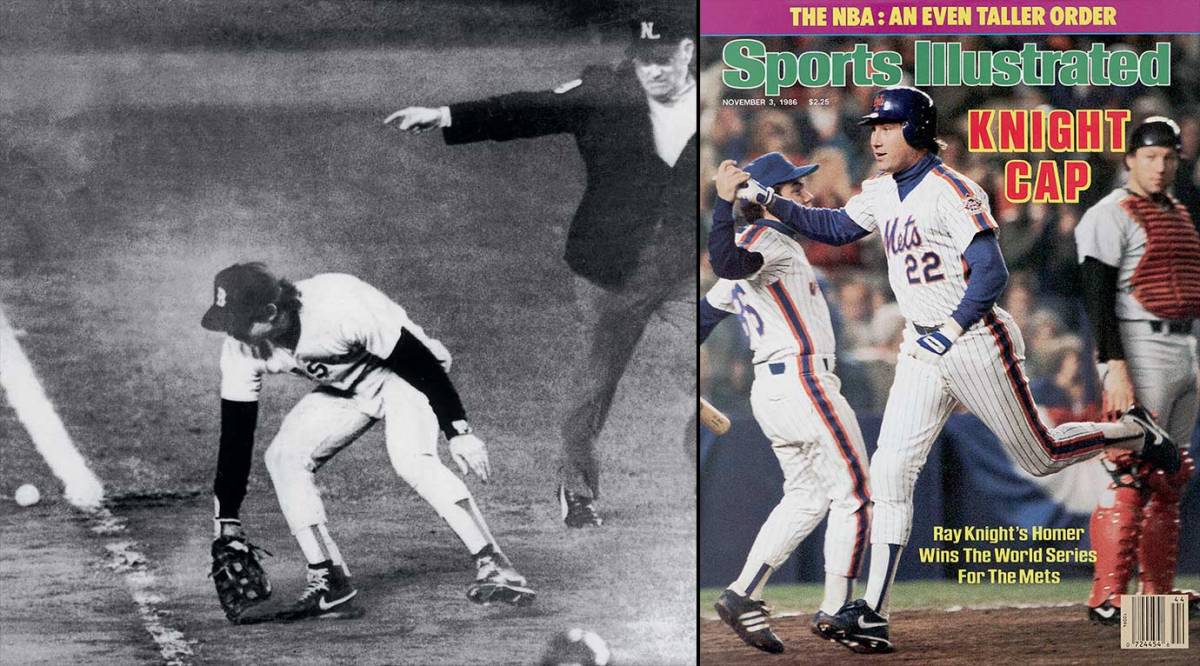

New York Mets last won in 1986

Pictured: Bill Buckner and Ray Knight

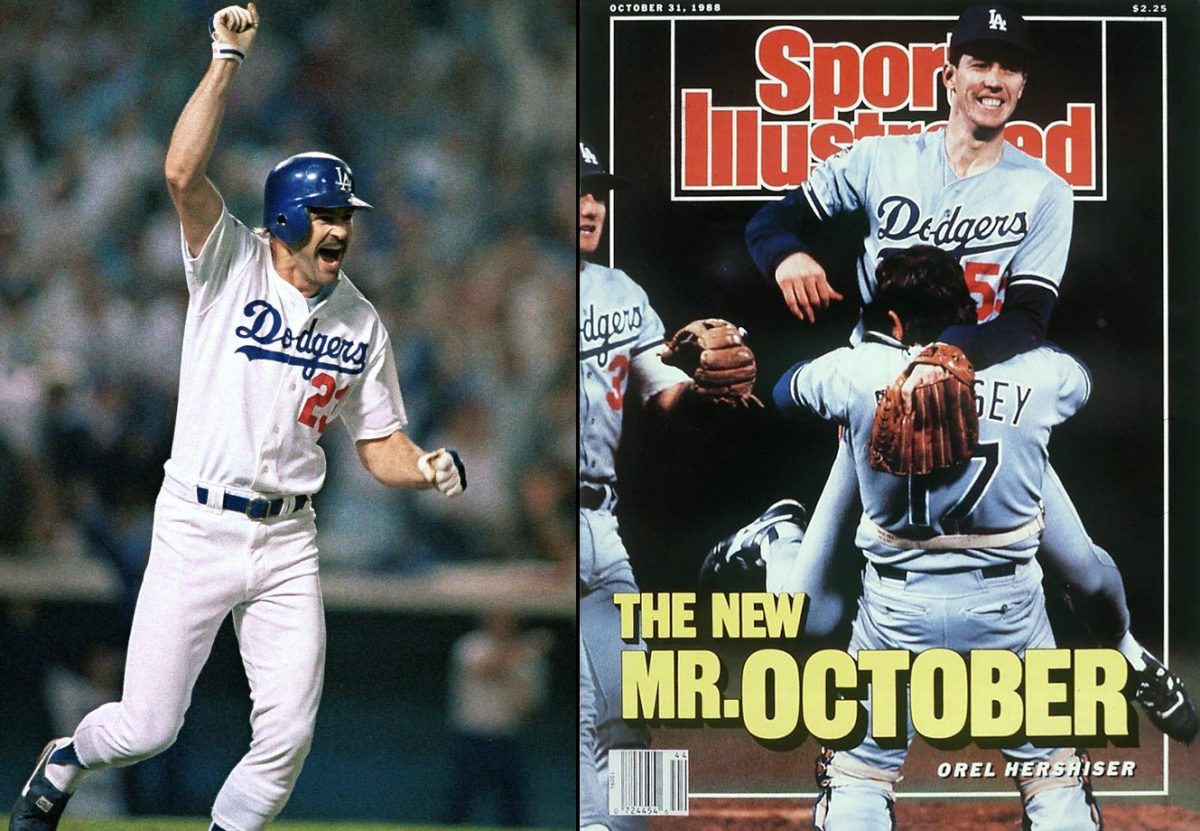

Los Angeles Dodgers last won in 1988

Pictured: Kirk Gibson and Orel Hershiser

Oakland Athletics last won in 1989

Pictured: Dennis Eckersley and Stan Javier

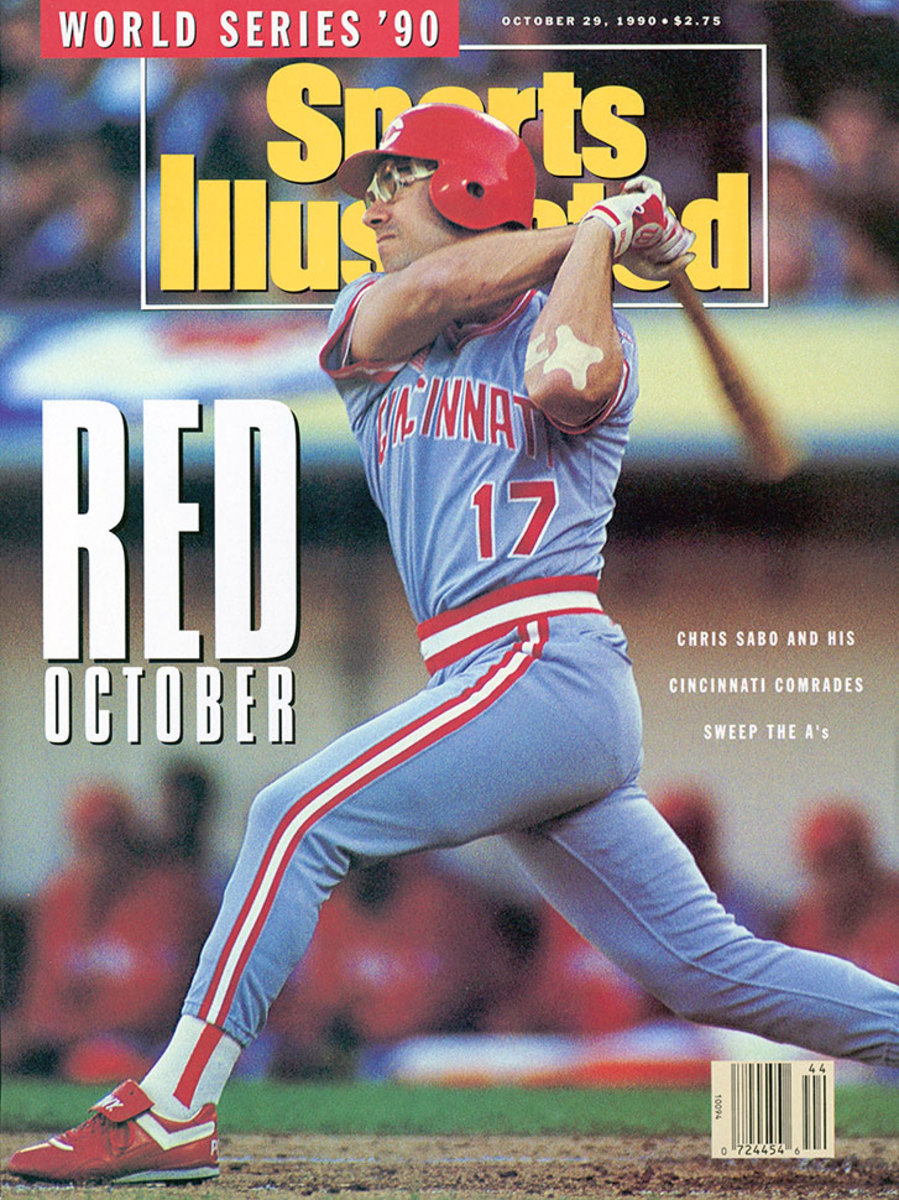

Cincinnati Reds last won in 1990

Pictured: Chris Sabo

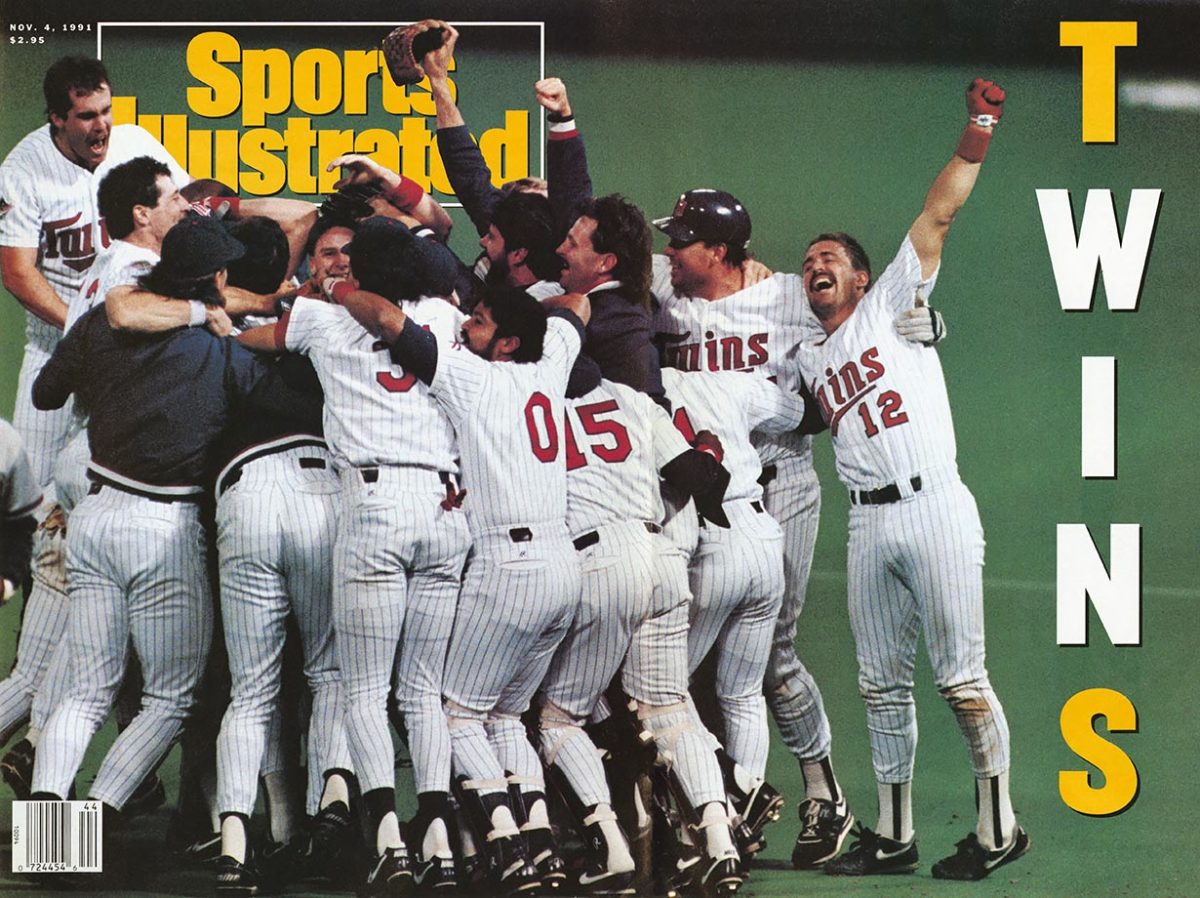

Minnesota Twins last won in 1991

Despite these questions, Washington is deep and balanced enough that it still looms as the best chance to take out the Cubs. And the difference may be Trea Turner. The rookie centerfielder/second baseman is a rare impact player with outlier elite speed and surprising power. Turner, 23, has 27 stolen bases and a .581 slugging percentage this season. In the history of baseball, only one player that young has combined power and speed like that: Shoeless Joe Jackson, who had 41 steals and a .590 slugging percentage back in 1911.

It’s mind boggling that the Padres, under then-new general manager A.J. Preller, traded such an obviously talented player. Washington GM Mike Rizzo pulled off a heist that is extending the team’s window to win by getting Turner and pitcher Joe Ross for Steven Souza, who was sent to Tampa Bay in the three-way trade. Then again, Turner has made a habit of surprising people. He told me he didn’t go to any high school showcases, and when I asked him why, he said, “Because I wasn’t very good. I wasn’t good enough to go on that showcase circuit or play on any big-time travel teams. I was probably only about 5'3" or 5'4" when I first got to high school.”

How a Cardinals fan learned to stop worrying and love (well, not hate) the Cubs

In the summer before his senior year at Park Vista Community High in Lake Worth, Fla., Turner, now 6'2", had drawn the interest of only one school: Florida Atlantic. A coach for his local travel team sent a video of Turner to a coach he knew at North Carolina State and told him the team would be playing the next week in East Cobb, Ga., against top travel teams. NC State watched him play that week and offered him a roster spot. When Turner began playing as a freshman, other teams couldn’t believe they had missed such an obvious talent and kept asking the Wolfpack staff, "Where did you find this kid?"

"I see these kids today making these flashy videos, promoting themselves, web sites with their stats ... and it starts when they’re freshmen in high school," Turner said. "I don’t know about that. What coach is going to look at that and say, 'Okay, this guy can play.' I don’t think so. It’s crazy how big it’s become to sell yourself."

Including the minors, Turner has 52 steals in 58 attempts this year. He is not just one of the fastest runners in baseball, but he also is one of the smartest. In the majors, he is 14-for-14 in stolen base attempts after the third inning, a key stat when you talk about having the conviction to grab a bag in the late innings of a playoff game. He also has one of the best first-base coaches in the business to guide him in Davey Lopes, who stole 557 bases in a 16-year major league career.

One minor weakness of the Cubs is that their starting pitchers are poor at defending the running game. Turner can exploit that flaw, and he can change the game from the batter’s box as well. He has hit 11 home runs in 61 games—more proof that the major league baseball is much livelier than it used to be.

"We’ve told our scouts when they project our minor league players to add on to their projections for power," said one scouting director. "You might have a prospect who looks like a 15- to 20-homer guy, but with the difference in baseballs now you have to say he’s capable of 30.

"Look at [Red Sox outfielder] Mookie Betts," continued the director, of the Red Sox outfielder who hit 27 home runs in five minor league seasons but has hit 31 for Boston this year. "The scouts liked him, but they didn’t see this kind of home run power."

Turner can be a difference maker in what figures to be the greatest postseason ever for dreaming about the end of droughts. The Cubs (108 years), Indians (68), Rangers (56), Astros (55), Nationals (48), Mariners (40), Orioles (33), Tigers (32), Mets (30) and Dodgers (28) represent 10 of the 13 longest world championship droughts in baseball. With less than two weeks left in the regular season, all of them still have a shot at fulfillment.