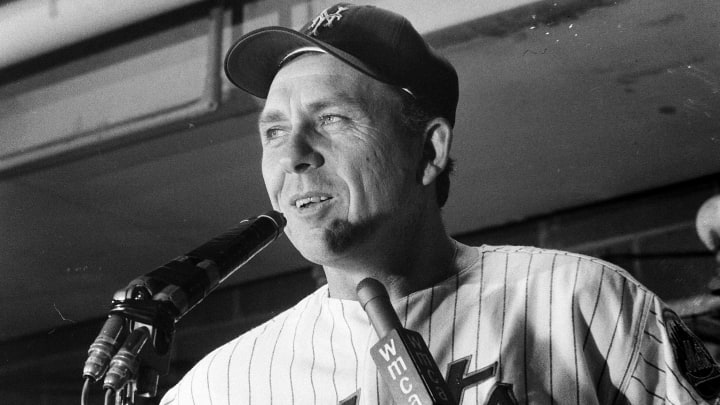

Gil Hodges Belongs in the Hall of Fame

Editor's note: Gil Hodges was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame by the Golden Days Era committee on Sunday.

In breadth of experience, wisdom and eloquence, no person in baseball imbues more integrity in his words than the great Vin Scully, now 94 years old. His latest work, a beautiful essay written for MLB.com, is required reading for the Hall of Fame’s Golden Days Era Committee, which on Sunday votes on candidates for enshrinement.

Scully makes the most convincing argument yet why Gil Hodges deserves to be in the Hall of Fame: It is the totality of a historic baseball life playing and managing, well beyond statistics.

Wrote Scully, “When one combines Gil’s impressive and consistent play on the field, his innovative managerial approach and leadership of the New York Mets culminating in the greatest upset in baseball history in 1969, and his unwavering commitments to his faith, family, country, and social justice, you have the rare instance of the ideal candidate.”

Scully was a Hall of Fame broadcaster for 67 years. Few people ever saw more games. To name the best player he ever saw, Scully said, is too difficult.

“However,” he wrote, “in terms of the players I watched who performed at a high level on the playing field, but at an even higher level off the field in how they lived and carried out their lives, my response is an easy one -- Gil Hodges.”

Wow. Over the past 25 years, late Hall of Famers Joe Morgan and Tom Seaver made similar endorsements for Hodges, who in his 52 years of eligibility instead has become by far the Hall’s cruelest omission. No one has received more votes or come so close—he once fell one vote short after a vote was disallowed—without getting into the Hall.

Hodges died from a heart attack in 1972 at age 47, just as he was about to begin his 10th year managing, all with recent expansion teams. His widow, Joan, is 95 years old. (She is also my aunt. Her mother and my grandmother were sisters who were born in Italy.) Joan has watched her late husband fall excruciatingly short of the Hall for half a century.

Enough. After all the years and all the near misses, it is time to finally get it right.

Hodges is famous, and for all the right reasons. He won a Bronze Star at Okinawa while putting his baseball career on hold to serve in the Marines. He has bridges, streets, high school stadiums and Little League fields named after him as much for his character as for his playing record.

He was the undisputed leader, first as a player and then as a manager, of two of the most famous baseball teams of all time, the Boys of Summer (1955 Brooklyn Dodgers) and the Miracle Mets (the 1969 New York Mets).

He was the best first baseman in baseball for more than a decade just as the game became integrated, first by his teammate Jackie Robinson. Gil and Joan immediately befriended Jackie and Rachel Robinson, helping in any way they could, such as grocery shopping for them, Scully wrote, in places that did not allow African Americans.

“Gil stood out,” Scully wrote, “as not only one of the game’s finest first basemen but also as a great American and an exemplary human being, someone who many of us were in awe of because of his spiritual strength.”

Scully’s eloquence should be enough for the committee. But sometimes basic facts win the room. Hodges is a Hall of Famer not because of his playing career or his managing career but because of both. Here are some simple truths about Hodges:

1. Hodges is the greatest slugger ever to manage a World Series championship team.

His playing/managing career is unique. Hodges hit 370 home runs. No World Series–winning manager is close to such a prolific home-run total. Rogers Hornsby is next at 301.

2. Hodges was the best first baseman in baseball over a 12-year period.

Hodges Ranks, 1948–59

| No. | All MLB | First Basemen | |

|---|---|---|---|

Home Runs | 344 | 2 | 1 |

RBI | 1,186 | 2 | 1 |

Total Bases | 3,184 | 3 | 1 |

Extra-Base Hits | 669 | 3 | 1 |

Runs | 1,032 | 3 | 1 |

Hits | 1,781 | 4 | 1 |

WAR | 44.3 | 13 | 1 |

3. Hodges also was the best first baseman of his time on defense.

He won three Gold Gloves and would have won more—but the award did not begin until 1957. Hodges won the first three handed out, beginning when he was 33 years old.

4. Hodges engineered the greatest upset in baseball history.

The Mets had never won more than 73 games entering 1969. With an offense that ranked next-to-last in OPS, Hodges expertly deployed platoons at several positions and led the Mets to 100 wins and one of the most iconic Cinderella stories in pro sports. The Mets ran down Hall of Famer Leo Durocher’s 92-win Cubs team, then went 7–1 in the postseason while taking out the 93-win Braves and the 109-win Orioles of Hall of Famer Earl Weaver.

5. Hodges was an innovator.

He popularized the five-man rotation, which became an industry standard. He did so to protect and develop young pitchers such as Seaver, Nolan Ryan, Jerry Koosman and Tug McGraw, all of whom were between 21 and 25 years old when Hodges joined the Mets. Those four pitchers threw a combined 85 seasons in the major leagues.

6. Hodges has the most Hall of Fame support of any player not elected.

In BBWAA voting, Hodges received more votes than 27 eventual Hall of Famers 146 times. Hodges is the only player to get 50% support from the writers and pass through the Veterans Committee and still not be elected to the Hall—and he did so four times.

7. Hodges had enough votes to be elected in 1993, only to be denied by a technicality.

Hodges and Leon Day received 12 of the 16 votes (75%, the threshold for enshrinement) by the 1993 Veterans Committee, only to have committee chair Ted Williams disallow the vote of Roy Campanella because Campanella, one of Hodges’s former teammates, did not attend the meeting in person. Campanella was in the hospital and would be dead in three months.

With Campanella’s ballot rejected, Hodges and Day fell one vote short (73.3%, 11 of the 15 votes). Two years later, the committee elected Day but not Hodges. Instead, it also elected Richie Ashburn. Hodges was on the same writers' ballot as Ashburn 14 times and received more support than Ashburn every time. And it wasn’t even close. Hodges received twice as many votes as Ashburn across those 14 writers' ballots, 2,773–1,274.

More MLB Coverage:

• Lingering Questions As MLB Lockout Puts Game on Hold

• Inside Baseball's Dangerous Game of Chicken

• Our No-Nonsense, Cut-the-Crap Guide to MLB's Labor War

• Rangers' Historic Spending Spree Probably Won't Pay Immediate Dividends

• The Sure Thing: Why the Rays Extended Baseball's Next Phenom

Tom Verducci is a senior writer for Sports Illustrated who has covered Major League Baseball since 1981. He also serves as an analyst for FOX Sports and the MLB Network; is a New York Times best-selling author; and cohosts The Book of Joe podcast with Joe Maddon. A five-time Emmy Award winner across three categories (studio analyst, reporter, short form writing) and nominated in a fourth (game analyst), he is a three-time National Sportswriter of the Year winner, two-time National Magazine Award finalist, and a Penn State Distinguished Alumnus Award recipient. Verducci is a member of the National Sports Media Hall of Fame, Baseball Writers Association of America (including past New York chapter chairman) and a Baseball Hall of Fame voter since 1993. He also is the only writer to be a game analyst for World Series telecasts. He lives in New Jersey with his wife, with whom he has two children.