Solidarity and Betrayal: The Rise and Fall of the Players’ League

How did baseball get here?

If this question seems relevant amid the ongoing lockout—echoing off the walls of a frozen game—a reasonable answer might be in the friction baked into MLB’s last collective bargaining agreement, in 2016. Another reasonable answer might suggest that the groundwork was laid in the agreement before that, in 2011, or two agreements before that, with the modern implementation of the competitive balance tax, in 2002. But if you’re going back two decades … well, you might as well go back all the way. Go closer to the origins of the historically fraught relationship between baseball players and owners. Go past the work stoppages of the last generation, past the fight for the first union in major professional sports and past, oh, another half-century and then some.

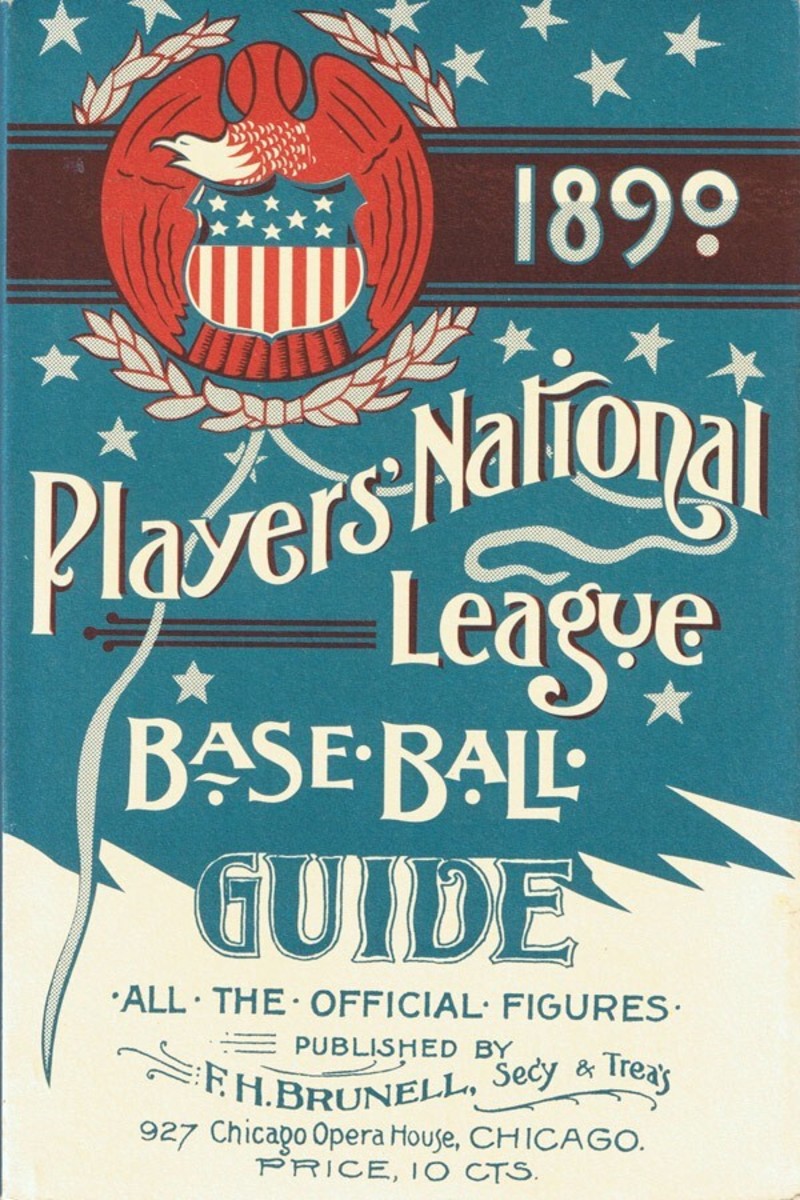

Welcome to the late 1880s. The American League did not yet exist. But the National League had been around for a little more than a decade—enough time for labor relations to have grown tense. The players felt that the owners’ vision for the game was fundamentally untenable for them. So they set off on their own. They had an idea for a version of baseball where they would have both a share of the profits and a say in the operations.

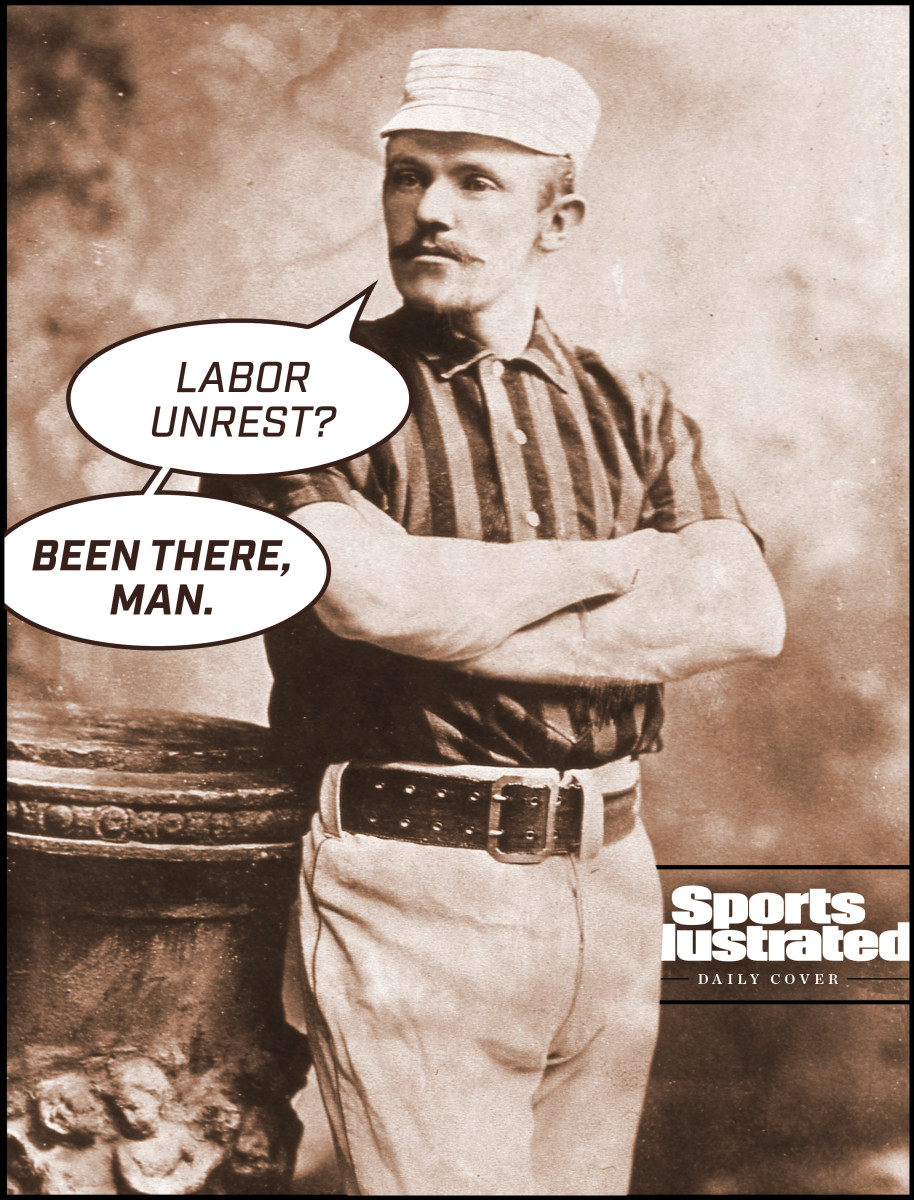

This was the Players’ League. The name captured the idea—a league by and for the players who made it. It was a radical concept, not just for organized labor in sports, but for organized labor, period. Led by a Hall of Fame shortstop named John Montgomery Ward, the league was born out of remarkable solidarity, with the majority of players who had been in the National League leaving to create the Players’ League. (The PL had 80 players who had previously been in the NL—enough to cover most of its rosters—while the NL that year was left with just 36.) For one year, they went head-to-head with their old bosses in the NL, and initially, they were successful. They drew more fans. Their players were more talented. Their brand-new ballparks were generally praised. They very well might have won—but then it all came crashing down with a twist of betrayal.

Yet it remains among the most interesting experiments in sports labor history, and its cause still resonates more than a century later.

“The issues that animated labor for baseball players in the 1880s have not disappeared,” says MLB’s official baseball historian, John Thorn. “A lot of that’s going to sound familiar.”

The Players’ League announced itself to the world with a meeting at a Manhattan hotel in November 1889. The lobby was full of players, reporters and fans alike, and all of them were handed a card at the end of the evening—a mission statement of sorts for the new endeavor. Written by a handful of the player-leaders, the card detailed how they hoped their work would differ from the National League, reading in part:

There was a time when the League stood for integrity and fair dealing, to-day, it stands for dollars and cents. Once it looked to the elevation of the game and an honest exhibition of the sport; to-day its eyes are upon the turnstile. Men have come into the business from no other motive than to exploit it for every dollar in sight. […] We believe that it is possible to conduct our National game upon lines which will not infringe upon individual and natural rights. We ask to be judged solely by our own work, and, believing that the game can be played more fairly and its business conducted more intelligently under a plan which excludes everything arbitrary and un-American, we look forward with confidence to the support of the public and the future of the National game.

It’s a player statement whose gist could have come from just about any point in the last century—a feeling that owners had stopped caring about the health of the game in the name of chasing extra profits. But if the sentiment seems timeless, it was accompanied by some very unusual, specific action (an entirely new league!), and it was driven by a very particular set of circumstances.

Chief among them was the reserve clause. Yes, a version of that reserve clause, which would frustrate players for nearly another century. When the NL first introduced the provision in the 1870s, it had actually been well-received: Multiyear contracts had previously been rare, which meant that most players had no idea where (or whether) they might play from one season to the next, and tying them to one team allowed for a new level of stability. But as the league expanded the powers of the clause through the 1880s, the players found that it became a source of frustration, rather than one of security. Soon, almost every player on a team was subject to the clause, and the average salary dipped accordingly.

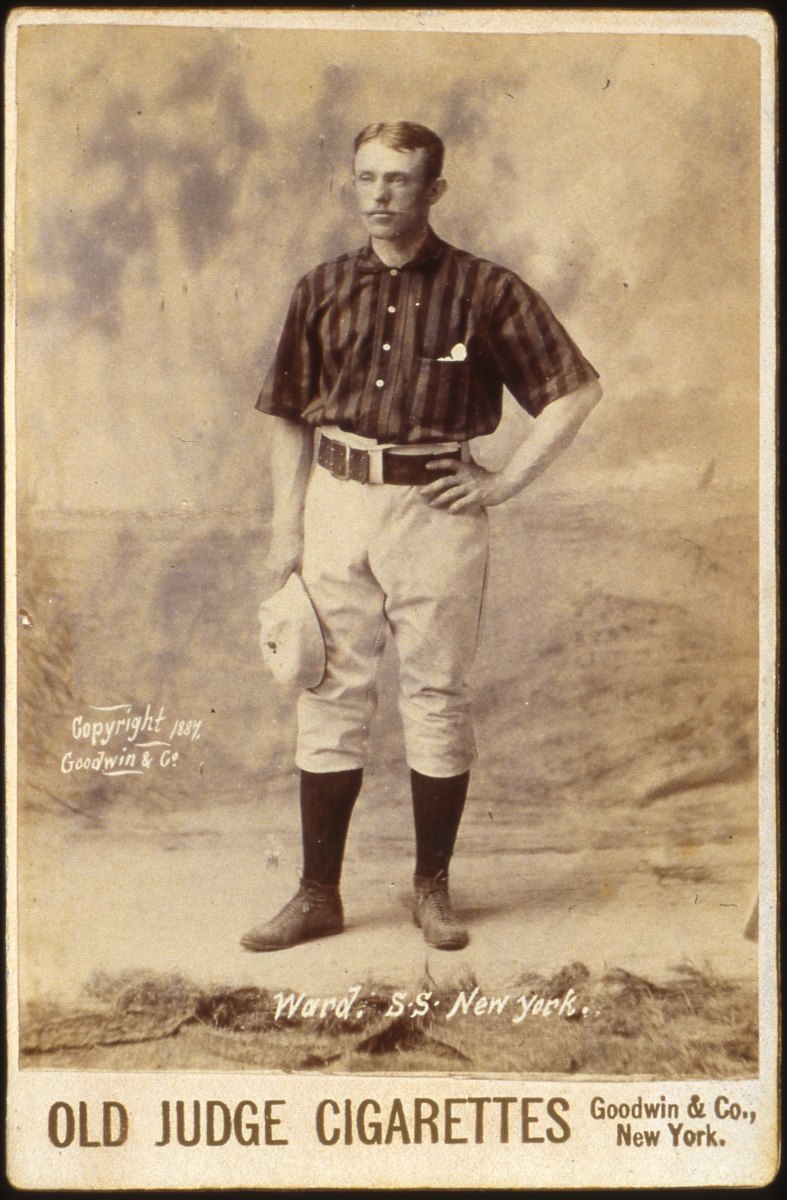

There were other factors that frustrated the players, too. While some teams had started to grow considerably more profitable in the 1880s, new forms of penny-pinching behavior were always popping up, like requirements for players to launder their own uniform or forgo free tickets for their wives. It all led the players to organize for the first time in 1885—through a group called the Brotherhood of Professional Base Ball Players. It wasn’t a labor union in the modern sense, and it had no formal, recognized powers. But it had a collective voice, and it fostered a sense of solidarity and mutual aid among players. There was no precedent for teams to keep paying someone who was injured or sick, for instance, but the brotherhood set up a relief fund to allow them to take care of one another and make sure that hurt players would have something. The group also fought against fines and examples of discipline that it found particularly egregious. And there was a natural choice for president—Ward. The shortstop was a star player and widely respected across the game. Though he was just 25 years old when the brotherhood was established, he already had experience leading as a player-manager, and he had valuable off-field perspective, too: While he played for the New York Giants, he’d started taking classes at Columbia Law School, and he’d just graduated with his degree.

But the NL rebuffed the brotherhood’s offers to draw up a new system for contracts or even to meet with them regularly. Within a few years, the situation had reached a tipping point.

The owners proposed a new salary plan after the 1888 season. Players, who would stay tied to their teams for life, would be graded from A to E: An A-grade player would receive the maximum annual salary of $2,500, while an E-grade player would be limited to $1,500 and have to work as a groundskeeper or ticket taker. (An early, radical attempt at maximizing value with positional versatility.) In other words, it was a combination of factors perfectly arranged to anger the players: a hard salary cap, a further entrenchment of the reserve clause and a tiered system designed to frustrate and embarrass those at the lowest level. The players, unsurprisingly, were furious. The owners tried to placate them by grandfathering in higher salaries and agreeing to implement the plan only over time. But that didn’t satisfy anyone.

The brotherhood considered going on strike in 1889; they even discussed walking out before the high-profile games on the Fourth of July. But Ward, in particular, had a different vision. The owners were clearly unwilling to work with them. The situation had only grown more tense in recent years. Why fight in such a frustrating system? Wasn’t there always going to be this kind of strife between the players and owners? Couldn’t they think bigger—toward their own vision of a baseball league?

“The idea of the players going on strike is one thing,” Thorn says. “But having a completely fresh league was another.”

Which is what brought Ward to leading up the group that passed out those copies of the mission statement in the hotel lobby that November. (After finishing out the season, of course: He went 15-for-36 in the postseason with 10 stolen bases as his Giants won the World Series.) The players weren’t going to simply negotiate with the owners. They were going to try to beat them at their own game.

One of the NL executives, Albert Goodwill Spalding, referred to the idea of a player-run league as “anarchy.” But Ward and the brotherhood came up with a remarkably detailed structure.

Their first matter, of course, was eliminating the reserve clause that tied players to teams for life. They did want some personal level of stability, and they knew that it was important for teams to be able to build their rosters more than one year at a time, too, but they needed a fair way to go about it. They settled on a system where contracts lasted three years and could not be bought or sold to another team. (This last part was particularly important to players who had compared their treatment under the old system to that of livestock.) Their salary was guaranteed, and once the contract was up, they would be free to negotiate and sign with any team they liked. As Ward wrote in a piece for Sporting Life, the players would go “free upon the market”—in other words, they would enjoy free agency, 85 years before the concept would come to MLB.

The players knew that they would need investors for the league; they simply didn’t have the money to set up anything like this on their own. (They especially needed help to construct their own ballparks.) But if they had to bring in outside capital, they didn’t want to replicate anything that looked like what they were used to in the NL, where the owners called all the shots. Instead, each team would be run by an eight-man board: four players, who would be elected by their teammates, and four investors, who would be elected by the other financial backers. The leaguewide governance would be handled similarly, with a board made up of two representatives from each team, one player and one investor. And while a profit-sharing system would include scheduled payouts for the investors, the initial round of profits each year would go to a prize fund, designed to incentivize clubs to stay competitive all season.

The players had other areas where their vision for baseball differed from the NL. (For instance, they added a second umpire to the field and got rid of a rule stating that a player could make a catch with his hat as well as his glove.) But their biggest changes were structural. They wanted a league where they felt they would be treated with dignity, where they would not be at the mercy of owners’ whims and where they could enjoy secure, long-term careers. They wanted to build the future of professional baseball—not just with their labor on the field but with their collective power off it—and they wanted to meaningfully share in its successes.

This, of course, was a nightmare for the owners in the NL. So they tried to stop it from happening. Shortly after the Players’ League was announced, the New York Giants sued Ward, and three other teams soon filed similar lawsuits against their respective stars for breach of contract. The hope was that a few big lawsuits would be enough to scare most players into staying with the NL—and if that wasn’t enough, clubs also tried to woo them by offering salary increases, the likes of which most players hadn’t seen in years.

It didn’t work. The Players’ League leadership was greatly respected by its base. Ward was admired as thoughtful and eloquent—he often wrote about the players’ cause in the press—as well as a talented player and strong teammate. (And he was still very much a man of the people: Before he was a Columbia-educated baseball star, he was a traveling salesman who’d been expelled from Penn State for stealing chickens from a nearby farm with his friends.) His legal education meant that he knew enough not to be terribly concerned about the lawsuits. He believed that the version of the reserve clause written in player contracts was not specific enough to withstand a legal battle, and, in January 1890, his belief was vindicated by a New York judge. Ward could proceed with the Players’ League, and, despite the best efforts of the NL, most of the biggest stars wanted to come along with him.

“They had the solidarity of something like 90% of the players,” says Robert Ross, a professor at Point Park University and the author of The Great Baseball Revolt: The Rise and Fall of the 1890 Players League. “The National League was offering unprecedentedly high salaries to try to get people to stay. … The players had a choice.”

And the majority of them chose one another.

“Now that the case has been practically settled, we will go to work and complete our task of organizing the strongest baseball association in the country,” Ward told a reporter as he left the courthouse after the judge ruled in his favor. “I don’t know just what course our enemies will pursue, but it is safe to predict the brotherhood will come out on top.”

For Ward and the Players’ League to come out on top, they would first have to go contend with their enemies in the National League. The PL had secured investment for eight teams, just like the NL, with seven of them in the same cities. Several of the ballparks that they had built over the winter were in the same neighborhoods as their counterparts in the NL. (In New York, they were directly adjacent—fans in Brotherhood Park would be able to hear those at the Polo Grounds.) And while the PL released its schedule first, with the belief that it would probably better for everyone if they could plan to complement one another in this department rather than compete, the NL countered by releasing a schedule that overlapped as much as possible—making sure that both organizations would be playing in the same cities on the same days for most of the season.

It was a daring strategy for the NL—hoping they might continue to draw big crowds even though they had been forced to populate their rosters with weaker players. And for the PL, it was a sign that they had succeeded in making the owners sufficiently nervous, a setup for a battle they felt they’d win.

“I feel so strongly about the success of our cause that I would be eager to change the schedule right on to their dates if they make a single change,” crowed pitcher Tim Keefe, a future Hall of Famer. “Why, bless you, we are not the weak side. We are the winners. We are the people.”

There was perhaps no better illustration of the dynamic between the two leagues than on Opening Day. The New York Giants of the NL raised a pennant declaring themselves the 1889 World Champions—it was their team, after all, that had won the World Series last October. But the New York Giants of the PL raised the same pennant—for it was their players who had made that victory happen.

There were three men from the 1889 World Series roster who had stayed on the 1890 NL Giants. There were 11 who went to the 1890 PL Giants. They wanted to make their view of the stakes very clear: The baseball that the fans enjoyed came from the players, and whatever their old team’s claim to the pennant, the spirit of that World Series club was now in the Players’ League.

The fans seemed to agree. The NL Giants, nervous about the possibility of being outdrawn, gave out 2,004 free tickets for Opening Day and reported total attendance at 3,524. The PL Giants, without any free tickets, blew them out of the water with more than 12,000.

It was an auspicious start for the Players’ League, “an experiment on our part to have the men who do the work participate in the profits of the pastime,” Ward called it. “If we are successful, it will be a demonstration that such a principle can succeed.” That kind of talk was appealing to many fans. While the PL was not formally affiliated with any big labor organization, it had the support of many of them, even getting influential union leader Samuel Gompers to come to a team meeting for the Philadelphia Athletics. It’s worth noting that this solidarity only went so deep—when the league raced to build its ballparks in time for Opening Day, it switched to non-union carpenters in some cities, and it set its leaguewide ticket prices the same as the NL, rather than reaching out to more working-class fans—but the PL certainly embraced it as a marketing technique. When the league started using the slogan “We Are the People,” fans embraced it as a chant.

Hard attendance statistics over the course of the season are hard to come by—both leagues had a tendency to inflate their numbers—but the PL appeared to regularly outdraw the NL. (A Boston Globe statistician put total season estimates at 980,887 for the PL and 813,678 for the NL.) The Players' League put the ball in play more often, the press hailed its quality of play and the unique governance structure had some early opportunities to shine. For instance, when the team in Buffalo looked like it was falling apart by July, the league stepped up in the interest of competitive integrity—determining that the club needed to bring in one additional infielder, one outfielder and two pitchers to ensure that the roster was up to snuff. (Imagine that in modern baseball!) It was totally contrary to how such a situation would have been handled in the NL. But it was how the players felt baseball should be run.

Which is all to say that the players’ experiment was working—in every way but one. They were losing money. So, too, was the NL, as it was clear that going head-to-head was proving disastrous for both leagues.

“The two opposing leagues are waging a war of extermination,” NL executive Spalding said at one point. “It cannot last. One of the two must give way.”

The players had worked hard to design a system they felt was fair, with its democratic governing structure and profit-sharing mechanisms. However, it wasn’t a true workers’ co-op; the players were some of the primary shareholders, but they were not the only ones, and they had to answer to their other investors, too. While some had come aboard because they believed in the vision for the league, most had signed on simply because they believed it was a good business idea, thinking that it would be successful because it had bigger stars than the NL. And when the league didn’t bring in serious money right away, those investors began to get nervous.

“The seeds of the destruction of the Players’ League in 1890 were that the players had to link with capitalists,” Thorn says. “It takes capital in the end. No matter how high your concept and how utopian your scheme—in the end, that takes money.”

And the NL’s shrewd ownership knew this all too well. Spalding, in particular, knew that the NL could not survive another year of competing with the PL; just one season of doing so had been all but financially ruinous. So he saw an opportunity to divide and conquer. At the end of the season, Spalding and other NL executives discreetly approached PL investors for the teams with the weakest financial situations, buying them out and convincing them to flip with a bluff about the financial picture in the NL. Spalding made it seem as if the NL had the resources to fight the PL for as long as it needed to—scaring investors and motivating them to cut panicked deals with the NL. Once a critical mass of investors had defected, there was no hope left for the players, despite their best efforts, and their league was gone.

“It really should have put the National League out of business,” Ross says of the Players’ League. “But it was the investor-owners, the non-playing owners, who sold them out. … The investors who were not ideologically interested in this sort of league, they saw this opportunity to join hands with the National League owners, and I think that was it.”

The NL’s owners had been financially battered by the whole exercise—but they walked out empowered. They decided that it would be as if the Players’ League had never existed in 1890; any player who had been subject to the reserve clause for an NL team in 1889 remained bound to the same team in 1891. The players, jaded by how quickly things had fallen apart, did not fight back in any meaningful capacity. Ward was devastated. He soon received a new contract—from one of the same executives whom he had just fought against—and found himself subject once again to the reserve clause he had worked so hard to topple.

“The players’ fatal mistake—and this was Ward’s fault as much as it was anyone else’s—was that they trusted their financial backers,” Ross wrote in The Great Baseball Revolt. “They believed that capital would act in the interests of labor. But building a league—constructing any industry—amid a political economy in which property does not come for free, is nearly impossible without an enormous initial sum of money, something the players did not have. Unable or unwilling to fight back, the players would not overturn the reserve rule again until 1975,” when the clause was removed in collective bargaining after Curt Flood had challenged it in court in 1969.

The Players’ League’s legacy faded from popular consciousness as quickly as it had sprung up. When Ward was posthumously selected to the Hall of Fame in 1964—almost three decades after the honor had been given to Spalding—it was primarily for his record as a player. But as for his work as an organizer? His experiment failed, his vision was radical and his strategy would become impossible to replicate. Yet he had established one of the first examples in what would be a long fight for player empowerment, and, more than a century later, his cause looks timeless.

When the league formally dissolved in January 1891, Ward gathered its members at a saloon for a wake of sorts, and he raised a glass for a toast: “Pass the wine around,” he reportedly said. “The League is dead, long live the League.”

He was answered by one of his associates, a man named Francis Richter, who had founded Sporting Life:

“Baseball will live on forever,” Richter said. “Here’s to the game and its glorious future.”

More MLB Coverage:

• Five Things to Know From MLB in 2021

• Top 10 Moments From the 2021 MLB Season

• MLB Players Can’t Stay Silent Anymore During Lockout

• Our No-Nonsense, Cut-the-Crap Guide to MLB's Labor War