The Path to a New CBA: Trade Economics for Rule Changes

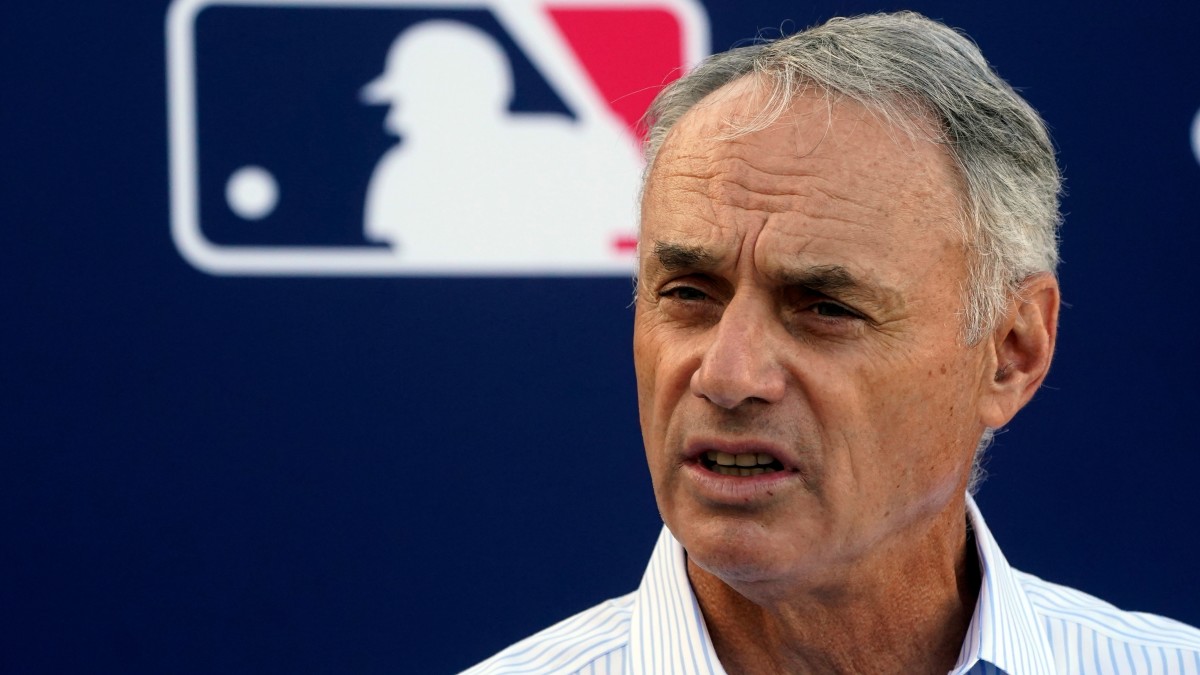

With players agreeing Sunday to reduce the time to implement rules changes, which means baseball will look differently next season, a path opened for commissioner Rob Manfred to get a deal that ends the baseball lockout: trade economics for quality of play.

His win can come from honestly telling fans that baseball at last is moving forward with a faster game with a bigger, more exciting postseason—the stuff baseball fans, not accountants, actually care about and, oh, by the way, means growing revenues long term. And he can do it with the players as a partner, not an adversary.

The beginning of such a win is to convince his hawkish owners that nudging the Competitive Balance Tax at the cost of about one Andrew Heaney per team ($8.5 million from the Dodgers after a 5.21 ERA over the past three years) is more than worth the cost of a better game.

And the owners better move quickly. Here is why. After this fight for a Collective Bargaining Agreement the next fight could be even more strident: back pay for players. Owners insist games lost means pay lost. Players insist there is no deal without back pay. This is the first lockout to cause the cancelation of regular season games, which means how this issue is decided will be precedent setting.

Manfred last season offered full pay for a COVID-shortened 154-game season. The union regards that as an opening. Owners regard last year as a unique health-driven circumstance. If the two sides reach a CBA agreement this week, maybe back pay isn’t a dealbreaker. Owners could pick up the tab in some percentage for two weeks of lost games—maybe even just one week if the players say they can get game-ready in 21 days rather than Manfred’s call of 28, as some people believe they can. But if this drags on? It becomes highly unlikely owners are footing the bill for a month of games with no revenue coming in.

This is not as simple as trading a pitch clock for a rise in the CBT. Negotiations are complex. The pre-arbitration pool, for instance, is a huge hurdle because the owners’ proposal does not have escalators. The players’ plan goes up $5 million each year. It adds up to a $300 million gap. Several other issues remain unsolved. This is about finding an exit ramp for the owners, which must come from non-economic issues given the stalemate on CBT.

“Quality of game is among the chief concerns of a group of owners,” said one high-ranking club executive. “They have been frustrated that they haven’t seen some of these rules changes sooner. There is some sentiment about the idea of trading economics for quality of play.”

When Manfred was named commissioner back in 2015, he identified pace of play as a priority. Since then, the dead time in a game has increased 17%. The game has never been slower. If you ask fans why baseball is losing its footing in the social consciousness, it is not the CBT. It is the pace and style of the game.

The players on Sunday agreed to implement in 2023 three rules changes 45 days after notice, rather than one year. Now Manfred needs to get agreement from the players on those rules changes and others as the way forward.

What Manfred could not do for seven years—get the players on board with fundamentally changing the game—can happen now. That will be a huge win. In 2023 you will not see defensive shifts take away hits. You will not see pitchers taking more than half a minute to throw a pitch; it will be 14 seconds with nobody on base and 19 seconds with runners. You will see bigger bases, which might encourage more stolen bases.

A cynic could suggest it was an empty move by the players, seeing that Manfred could impose those same changes next year anyway. But to truly grow the game, you need a partnership, not a mandate from above. With two players on the competition committee, the 45-day notice also means the sport can be as nimble and reactive as the NFL and NBA when the entertainment value needs to be preserved (such as when and if pitchers find a workaround to the pitch clock, such as repeatedly stepping off).

Manfred has two key moves to make to create this exit ramp. First, he tells the players agreement on the rule changes and the 14-team proposal must be part of the agreement. It must be part of the economics-for-game-quality trade. It also makes so much more sense than Max Scherzer’s silly “ghost win” idea. The “ghost win” is used in the KBO because they have a completely balanced schedule. And in seven seasons using the “ghost win” format there, the team handed a win to start a best-of-three series won every time. Who wants a format with fake wins and no drama?

Even Scherzer’s agent, Scott Boras, knows the 14-team proposal is a better plan that drives more money to players, fosters more competition and discourages tanking. Boras said in 2021, “I think it’s good for baseball because it creates competitiveness.” And that was in favor of a 16-team format.

Players have told the owners they will not move off the 12-team format. Call them on it. Are players really going to keep the game shut down over a 14-team plan that actually sends more money to the players and puts another 52 players in the postseason? Not when they are getting economic wins—their chief objective.

Sign up to get the Five-Tool Newsletter in your inbox every week during the MLB offseason.

Manfred’s second task is to convince his mid- and small-revenue hawks that they should not die on the hill of the CBT. The owners have offered a $220 million threshold in each of the first three years, followed by $224 million and $230 million. Players’ proposal starts at $238 million and rises to $263 million.

Split the first-year difference—halfway, $229 million, or just about one Heaney more from where the owners stand now—and work on the escalators. Owners overvalue the CBT as it relates to competitive balance. Another $9 million in the first year is not a fundamental change. In 2016, a record six teams went over the CBT. Adopting brutal efficiency, all but two teams stayed under it last season, while seven spent within 6% of it. The 14-team playoff format becomes another mechanism for competitive balance.

Thinking about how we got here helps us get out of here. Players started out asking to change three pillars of the CBA: free agency arbitration eligibility, arbitration eligibility and revenue sharing. All three changes came off the table. They have won a historic raise in the minimum salary and the new concept of a bonus pool, both of which address their concern of getting more money to young players. The CBT is going to rise well beyond the tiny increments it did in the previous three CBAs. Those are all clear economic wins for the players. But they do not fundamentally change the system.

The win for the owners is in giving fans a better product, which grows revenues. If Manfred delivers a better on-field product in partnership with the players, he will have won on the higher ground.

More MLB Coverage:

• Baseball Should Expand the Playoffs to 14 Teams

• ‘Since When Were Women Allowed’: Inside Their Push to Break Into Baseball

• MLB Owners Fail to Realize Their Own Foolishness

• This Is the Path MLB Chose

• Baseball Hurtles Itself Deeper Into Danger