Cuban defector Aroldis Chapman remains a mystery -- and a risk

What's it worth?Aroldis Chapman had tossed the question around in his mind more times than he could count. What was it worth to leave everything he had ever known for all that he didn't, he would wonder -- but never aloud.

Talking, Chapman figured out, was what had gotten him in trouble the first time. In his initial defection attempt, there were too many people involved, which meant too much talk, and too much talk meant too much risk. Cuban authorities had caught wind of his escape before he had even set foot offshore.

This time he knew better than to breathe a word of his plan to anyone, including his pregnant girlfriend, who rested beside him for what could be the last time in a long time.

"What would you do," he asked her, "if I didn't come back?"

Raidelmis Mendosa Santiestelas' hands circled the baby in her belly.

"Stop talking nonsense," she said.

Days later, Ashanti Brianna Chapman was born, but Aroldis was already gone from Holguín. For good.

*******

What's it worth to forgo holding your baby or hearing her laugh? "I knew I wouldn't meet my daughter for a long time, but I thought it was what I had to do," Chapman says now. "I made my decision."

On July 1, the 21-year-old had been in his Rotterdam hotel room no more than an hour after the team had landed for the World Port Tournament when he grabbed a pack of cigarettes and told his roommate he was going for a smoke. He felt for his passport in his pocket and headed out the hotel doors to where a car waited for him, just as planned. He jumped in the passenger seat and closed the door. By shutting that door, he opened countless others, to an eventual bidding war in which several major league teams, virtually sight unseen, are now deciding whether to ante up millions in hopes that Chapman will be that rarity: the heralded Cuban defector who lives up to his tantalizing hype.

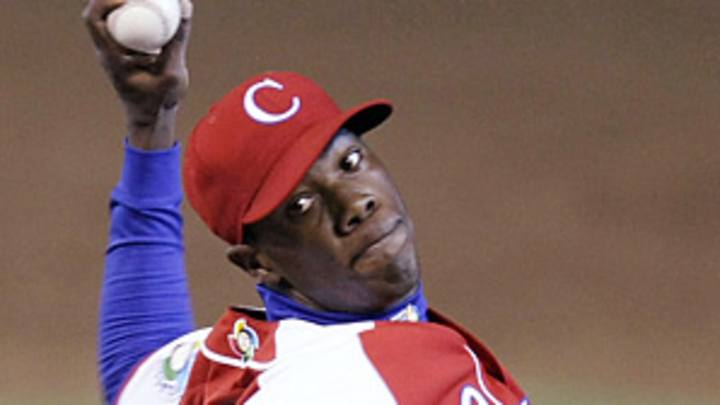

Nearly two years earlier, at the age of 19, Chapman had announced his arrival by pitching a standout game in the second round of the 2007 World Cup in Taipei. He followed that up with a stellar outing in the semis seven days later. He was a scout's dream: Here stood a 6-foot-4, 185-pound, teenage lefty who had just struck out 20 batters in 15 innings over two starts.

"He's a left-handed pitcher who throws 100 miles per hour," says one international scout with two decades of experience. "You can travel the world and not find that."

A year and a half after Chapman's World Cup appearance, MLB scouts had their radar guns trained on him at the 2009 World Baseball Classic in Mexico and the U.S. They had all seen or heard about his show in Japan and now they longed for an encore. Also trained on him were the watchful eyes of those looking to help him defect -- and those of the Cuban authorities making sure he didn't.

Before he had thrown his first pitch of the Classic, the legend of Aroldis Chapman had been created. And, some would argue, so had the myth.

*******

What's it worth to drop the familiar for the unknown? Chapman has spent most of his life confronting that question. It had popped up a dozen years before he would defect, when the neighborhood kids in the province of Holguín (north of Guantanamo, on the island's eastern shore), short one player for their baseball game, spied nine-year-old Aroldis. His long, lanky limbs suggested "first baseman," and they asked what seemed like the most innocuous of questions: Wanna play?

Aroldis' father, Juan Alberto Chapman Benett, trained boxers. He and his son had spent hours on end learning how to throw punches, not baseballs. But nine innings after filling in at first base, the little pugilist was forever a pelotero (baseball player).

The freshly minted ballplayer soon began dreaming of making Cuba's vaunted national team. Like almost every other kid on the island, he looked up to right-hander Jose Contreras, whom Cuban leader Fidel Castro dubbed El Titan de Bronce (the Bronze Titan) after he struck out 13 batters in 18 innings -- on one day's rest -- to beat the U.S. in the 1999 Pan Am Games championship. But unlike almost every other kid, Aroldis showed the ability to match his aspirations. Cuba did what it usually does with athletic potential and sent him to a school where he learned about math and science along with base running and situational hitting. His height and his reach made him a natural fit for first base, his primary position ever since he picked up a baseball. All of that changed one day in 2003 when, at age 15, Aroldis took infield practice.

His throws had always smacked the glove harder than most. But on this day, as he scooped up the ball and launched it across the field just as always did, a passing pitching coach noticed that Aroldis had an awfully strong arm to be mainly tossing the ball back to the pitcher between plays. The coaches pulled Aroldis to the side and told him he would be taking the mound. By the following day, he was a pitcher.

*******

What's it worth to get Chapman off the island and into the majors? The smugglers who offered to help him defect that spring day in 2008 could only imagine. Six years earlier, in 2002, Contreras received the most money ever given to a Cuban when the New York Yankees signed him for $31 million over four years -- and that was during a time when the Yankees said they were cutting payroll. For all that Contreras was in Cuba -- righty, powerful, proven --Chapman countered with his left-handedness, youth and projection. So what if he had just come off a losing season, finishing 6-7 in Cuba's highest league, the National Series? He could do what only a precious few current big leaguers (Randy Johnson, CC Sabathia and Billy Wagner) can: throw a left-handed, triple-digit fastball.

It was worth it for Aroldis Chapman to try to get out.

The smugglers' plan was doomed before their escape boat hit water. Chapman says the man who had offered to arrange his escape not only was caught by Cuban authorities before Chapman and the others boarded their boat to leave, but he also was talking. Chapman had figured out that the man must have given him up to the authorities when Aroldis was summoned by Raul Castro, Cuba's president, to his office to discuss his planned defection.

This is the end of my career, he thought as he headed over to his meeting from where he was training in Havana with other Olympic team hopefuls. He knew that athletes who try to defect don't come back to play on the national team and that he would face a two-year suspension from the National Series, as well. But more than anything, "I felt badly, not so much for me but for my family," he says, knowing that they, too, could face punishment.

Chapman says authorities removed him from the Olympic team in reprisal. "They didn't take me [to Beijing] because they said they weren't certain that I would return," Chapman says.

Others are not so sure that is the real reason. Dr. Peter Bjarkman, a foremost Cuban baseball scholar and chronicler, suggests that Chapman has reframed his Olympic exclusion as a punishment, rather than a performance-based roster cut. Bjarkman writes that the June 2008 Jose Huelga Tournament in Havana is when Chapman "pitched himself off" the Olympic team as he "displayed little control and less confidence, being knocked out early in his final appearance versus tame Puerto Rico by his own extreme wildness."

But the following winter, at the start of Cuba's National Series, Chapman seemed to recapture some of the magic that had enthralled scouts at the 2007 World Cup. He jumped off to a 6-0 start with a 1.89 ERA, according to Bjarkman's accounts, and struck out 52 batters in less than 48 innings, pitching his way back onto the Cuban roster for the 2009 World Baseball Classic.

In his first game at the WBC, a 5-4 win over Australia in Mexico City, he dazzled scouts even if he didn't completely baffle batters. He launched 16 pitches registering 99 mph and four in triple digits on the gun while giving up three hits in four innings. In the next round, against Japan at San Diego's Petco Park, Chapman was frustrated by more disciplined hitters and a stingier strike zone than he was used to in Cuba. He surrendered three earned runs in 2 1/3 innings with three walks and one strikeout in a 6-0 loss. He bristled at umpires when he disliked calls and ignored teammates when pulled from the game even thought he knew all eyes were on him, all of the time.

Only the Cuban security guards watched Chapman more closely than scouts did during the Classic. He had offers to defect, but no intentions. His good behavior meant that when he returned to Cuba, the security force ordered to keep a close watch on him loosened its grip. The extra breathing room only breathed new life into his dreams of leaving. He had now played in the big stadiums and under the bright lights of an MLB field.

He would wait until July's World Port Tournament in Rotterdam -- a smaller tournament populated by what Bjarkman calls "the B-team" of the Cuban national roster. More modest talent meant less security to breach as Chapman walked out of the hotel and over to the car. To say that all went according to plan in Rotterdam would be inaccurate; things went even better. Chapman says Cuban officials broke a longstanding protocol of collecting players' passports at the airport. "They didn't have time to take my passport," he says, and Chapman didn't have time to change his mind, hopping into the car outside the hotel.

He eventually would pass through Belgium, France and Spain. He would find his way to Edwin Mejia of Athletes Premier International, a budding sports agency in search of its first big league client. Mejia would lead Chapman to Andorra, the tiny nation nestled between Spain and France where he could establish residency outside the U.S., an MLB requirement for international free agents. Mejia then shepherded Chapman to New York and Boston to begin meeting with teams.

Chapman's next stop? It might be just as uncertain as those first steps Chapman took out of his Rotterdam hotel.

*******

What's it worth? The question is no longer Chapman's to answer. What's it worth, major league teams now ask, to sign a left-hander whose pitches are as fast as his track record is inconclusive?

The velocity of Chapman's primary pitch is well-documented: It's blindingly fast. So much so that some scouts wonder if its speed obscures his weaknesses. Chapman has holes, and is aware of them. "I need to improve my control," he says. "In the last two years, I've had more control. I've trained a lot and improved a lot. Now, I think I have a little more room for improvement."

In his four years in the National Series, he had a 24-21 record with a 3.72 ERA. Almost as notable as his 379 strikeouts in 341 2/3 innings are his 210 walks. His career bases on balls per nine innings is 5.37, a stat that would rank him last -- below Arizona's Daniel Cabrera (5.24) and Milwaukee's Seth McClung (5.31) -- among the 245 major league pitchers who have thrown at least 341 career innings. And that's calculated without adjusting for a softer strike zone and freer swingers in the Cuban league. "In Cuba you knew you could throw a bad pitch and a batter would swing at it," Chapman admits. "In the big leagues, that doesn't happen very often."

Over the summer, Clay Davenport of the baseball think tank Baseball Prospectus employed mathematical formulas to try to translate Chapman's statistics into numbers that might indicate how he'd do in the majors. Davenport's results projected that Chapman's would compile a 10-23 record with 303 strikeouts in 292 2/3 innings and an ERA of 6.66. Davenport's analysis concluded that the left-hander's translated stats correlated most closely at the same age with those of prospects Adam Bostick (currently in the New York Mets' system), Ted Langdon (formerly in the Cincinnati Reds' organization) and Joe Young (formerly in the Toronto Blue Jays' system), none of whom advanced beyond Triple-A. Bostick and Langdon converted to relief while Young remained a starter. Fourth on that list of comparable pitchers was Los Angeles Angels closer Brian Fuentes.

These statistics reinforced a concern of several executives who spoke to SI.com. "His secondary pitches are just not that good," says one high-ranking NL team official. Chapman, however, feels that he has command of his complementary pitches, which include a sinking fastball, curveball, slider, changeup and forkball. "My [secondary] pitches, I don't think I have a problem," he says. "The fastball is the one I have a harder time controlling because it moves on me a lot. With my other pitches, it's not a problem."

Chapman expresses reluctance to move to the bullpen, though he worked as a closer for part of the 2006-07 National Series season. "It went OK, but I like being a starter better," he says. "The difference in starting the game is that you can impact the game greatly. You can pitch a lot of innings. As a closer, you only get one or two innings. You pitch more frequently, but I don't have a lot of interest in being a closer."

Another area of concern, which no analyst's formulas can predict and no scouts' radar guns can measure, is maturity. Bjarkman, the Cuban baseball scholar, publicly called Chapman "uncoachable" while some scouts took note of how he grimaced and writhed at an uncomfortable strike zone at the WBC. Chapman explains it more as a cultural difference rather than a personal shortcoming. "In Cuba, the athletes fight a lot with the umpires. They're always arguing with the umpires," he told SI.com. "Here, that's rare."

Questions about his makeup resurfaced last month when Chapman orchestrated a defection of a different sort, abruptly ditching Mejia, his agent, in the middle of contract negotiations and signing with the Hendricks brothers, who boast a client list of Roger Clemens, Andy Pettitte and, most recently, fellow Cuban defector Kendry Morales, with whom Chapman had spoken during the 2009 playoffs. One NL executive who has followed Chapman says that fellow Cuban players acquainted with him have described the pitcher as temperamental and crazy.

That same executive has a much more fundamental concern: He hasn't seen enough of Chapman. There have been no open showcases for him, usually a requirement for high-profile international free agents. "If he's that good, why aren't you showing him off?" the executive asks. "Why not throw him in the Dominican Winter League and let him tear up the competition and drive up his price?"

Figures as high as $60 million over six years have been floated around baseball circles, with the Yankees and Red Sox frequently mentioned as suitors. In recent days, however, Chapman's rumored price tag has shifted from Daisuke Matsuzaka money ($52 million over six years) to the more realistic Stephen Strasburg range ($15.1 million over four years). SI.com sources place at least one big-market club's offer at $12 million over three years. Even Chapman's hallmark velocity is being called into question, however: One source told SI.com that the left-hander's fastball did not exceed 92 mph during a private workout last month.

One of the NL executives who has followed Chapman says that money is just one issue. "The real story with Chapman is to come back three years from now and see where he is," the exec says. In that time, his contract will be signed and his talent a known commodity. And his daughter, whom Aroldis has not seen, will have long since spoken her first words and stumbled through her first steps. Then, and only then, will everyone be able to answer: What's it worth?

Staff Writer, Sports Illustrated Staff writer Melissa Segura made an immediate impression at Sports Illustrated. As an undergraduate intern in 2001, her reporting helped reveal that Danny Almonte, star of the Little League World Series, was 14, two years older than the maximum age allowed in Little League. Segura has since covered a range of sports for SI, from baseball to mixed martial arts, with a keen eye on how the games we play affect the lives we lead. In a Sept. 10, 2012, cover story titled, The Other Half of the Story, Segura chronicled the plight of NFL wives and girlfriends caring for brain-injured players. In 2009 she broke the story that MLB had discovered that Washington Nationals prospect Esmailyn Gonzalez, who had been signed to a team-record $1.4 million bonus in 2006, was really Carlos Alvarez and he was four years older than he had claimed to be. Segura graduated with honors from Santa Clara University in 2001 with a B.A. in Spanish studies and communications (with an emphasis in journalism). In 2011, she studied immigration issues as a New York Times fellow at UC-Berkeley's Graduate School of Journalism. Before joining SI full-time in 2002, she worked for The Santa Fe New Mexican and covered high school sports for The Record (Bergen County, N.J.). Segura says Gary Smith is the SI staffer she would most want to trade places with for a day. "While most noted for his writing style, having worked alongside Gary, I've come to realize he is an even more brilliant reporter than he is a writer."