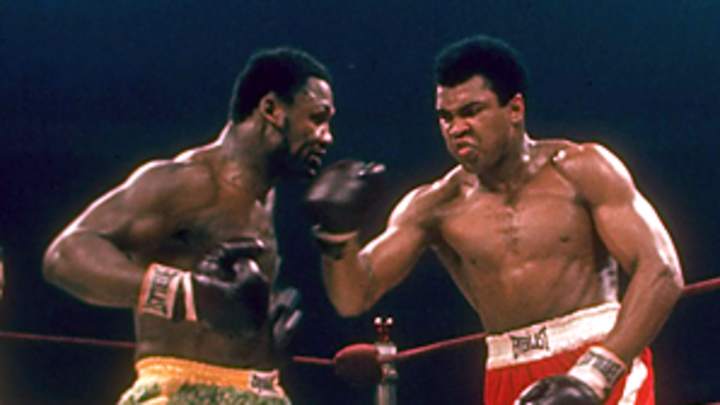

Icons Frazier, Holmes helped usher in boxing's golden age of Ali

Seated at a small, cloth-covered circular table that seemed insufficient for its guests, old friends, former sparring partners, Larry Holmes and Joe Frazier laughed, appraised, remembered and spoke truth, as they know it.

Boxing greats from an era that produced so many memories, both fighters have -- over several decades -- come to terms with the fact that whatever it was they accomplished in their professional lives, Muhammad Ali will always be Muhammad Ali.

"Keep memorializing him," said Holmes, still very much the imposing figure that stopped Ali for the only time in his career 30 years earlier. "You say he was the greatest, that's fine by me. But in my opinion, he wasn't."

Not Ali?

"Me," he said. "Ali was the greatest of all time. He floated like a butterfly and stung like a bee, but then he met me. I plucked his wings."

Frazier, a wheelchair parked at his side, waited before chiming in.

"I think I'm the greatest," he said softly under a big-brimmed hat that hid light from his eyes. "We had two good wars, there's no doubt about that. He won two and I won one. But you look at him now, you know who won them all. I can deal with that."

"It was a fight for Joe," Holmes added. "It was a cakewalk for me."

While two of the 10 boxers featured in the award-winning documentary Facing Ali bantered about their lives, their experiences with Ali, and their place in boxing lore, Derick Murray stood at a distance, managing to catch only snippets of the exchange -- Frazier can be difficult to understand even when sitting next to him.

Tall, slender and well-dressed, Murray obsesses about what makes people go. Particularly if they're successful. It's what drove him into filmmaking and storytelling. Having worked with a large enough sample, the Canadian says he believes there's a common thread among individuals that excel.

"Never quit. Perseverance. One-hundred percent. No matter what comes at you, believe in yourself and go for it," the producer said. "When you're in the seventh round and you're losing, you don't walk away."

Murray and Uganda Rising director Pete McCormack spent, over the course of several months, three hours to a day with their subjects -- Frazier, Holmes, George Chuvalo, Sir Henry Cooper, George Foreman, Ron Lyle, Ken Norton, Earnie Shavers, Leon Spinks, and Ernie Terrell -- all men who gave as much as they could of themselves against Ali.

"We didn't want a boxing film," Murray said. "We didn't even want a sports film. We wanted a film that these 10 boxers would reveal who they were. Where they came from. What motivated them. And clearly, for each of them, what it was like to step in the ring with Ali. We wanted that connectivity to their being."

Traveling across the country from Pennsylvania to publicize the documentary's world television premiere Feb. 15 at 9 p.m. ET/PT on Spike TV, the boxers' presence in a posh Pasadena, Calif., hotel provided each a rare opportunity to remember the past with someone who knows what they're taking about.

Long gone, they said, are the days when boxing regularly appeared on network television. When champions fought four and five times a year. When more than a couple boxers were among the most recognizable athletes in the world. When fighters sacrificed because that's what they were supposed to do. When trainers were former boxers who knew what it was like to get clipped with a right hand. Now, the division they once ruled is overrun by heavyweights with funny foreign names. Little guys with big attitudes are making even bigger money.

Things aren't the way they should be.

"I love boxing when I see boxing," said Frazier, who celebrated his 66th birthday in January. "But then you never see boxing. What is it, that ultimate something? They knock a guy and he slipped down and he jumped between his legs. You knock a man down, you go to a neutral corner."

It was then that I informed the pair of my regular beat covering mixed martial arts. That information was met with a pause and some looks before the conversation continued. It was my hope, I told them, they might have a story or two to about mixed-style fights. Had a wrestler ever challenged them? Did a karate practitioner get too brave along the way? What did they make of Ali's foray to Tokyo in 1976 to take on Japanese pro-wrestling star Antonio Inoki?

Neither had much to say in the way of mixed-style matches. And Holmes, a wrestler and dabbler of karate in his youth, opined that winning and losing in MMA is "a matter of luck," not skill. That all that martial arts stuff goes out the window with a solid punch to the mouth.

MMA, it seems, is not their thing. But what of the notorious bout in Tokyo seven months after the "Thrilla in Manilla" in which Ali made $10 million to face Inoki in a mixed-rules affair?

"Ali said it was crazy because he couldn't walk after that," Holmes said. "The guy kicked him all in his leg. I didn't think Ali could beat the guy by wrestling because the guy is a wrestler. But if the guy stood up and tried to box him, Ali would put him out."

Frazier, who went 41 rounds with Ali, said he wasn't aware of the bout. And even if he was, there's a good chance he wouldn't take the time to talk about it.

"You know these guys made each other," Holmes, 60, said as he looked across the table at the broken-down Frazier. "Ali made him. He made Ali. You can talk about the "Sugar" Ray Robinsons, Dempseys, Marcianos, but you have to look at the three fights with Frazier and Ali. That's what brought boxing alive, having those kinds of fights."

Frazier sat quietly for a moment, accepted the compliment from a fighter whose rib he once busted in sparring, and lightly grabbed my wrist with meaty hands that are calcified around the knuckles.

"Forty years down the road," said Frazier, "I'm just happy to be here."