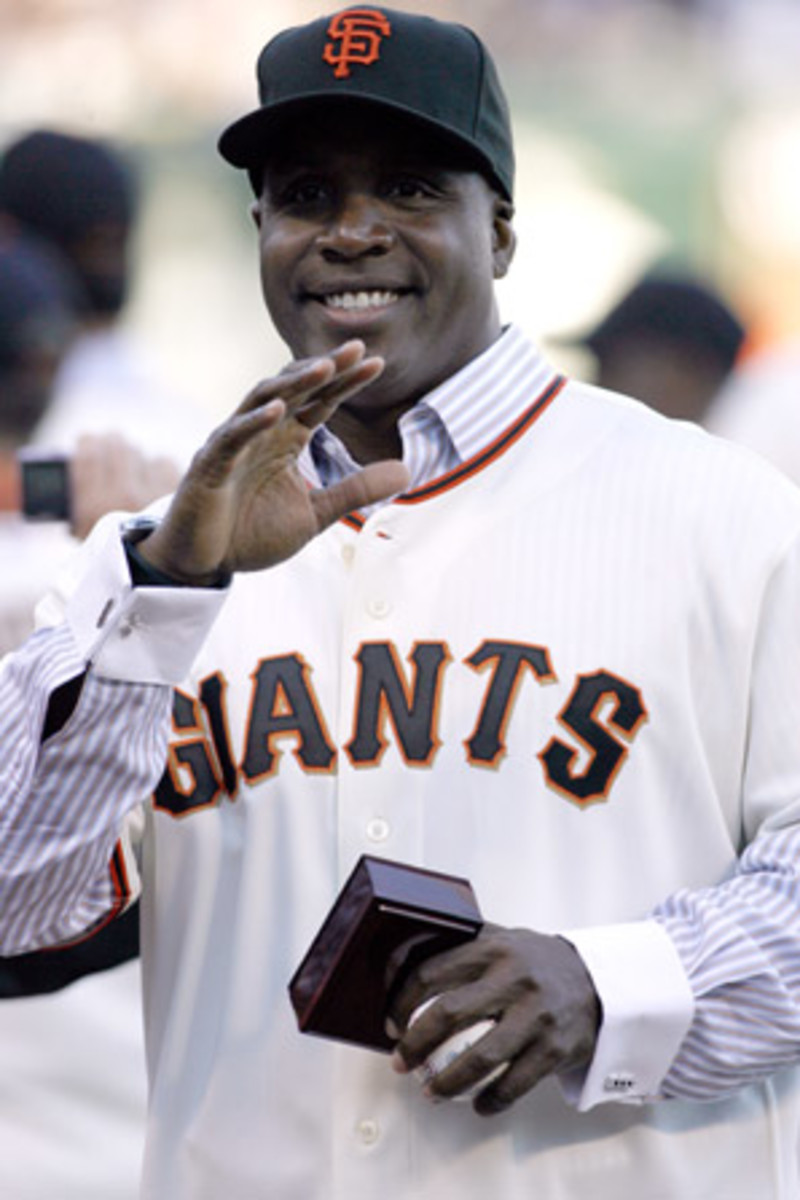

Barry Bonds has disappeared into own world -- and nobody cares

Last weekend, Barry Bonds told the San Francisco media that he is not ready to retire from baseball.

Nobody cared.

He said that he is proud of Mark McGwire for coming clean.

Nobody cared.

He showed up an hour late to AT&T Park for a reunion of the 2000 NL West-champion Giants.

Nobody cared.

Truth is, Barry Bonds could arrive tomorrow at the top of the Empire State Building fresh off of gender reassignment surgery while wearing an ASHLEE SIMPSON 4-EVER! T-shirt, balancing three hairy-eared dwarf lemurs in each hand and singing Queen's Bohemian Rhapsody ... and nobody would give a damn.

Absolutely nobody.

Karma -- it ain't no joke. For most of his 22-year major league career, Bonds was the undisputed president and CEO of the AMSAPS (Arrogant, Mean-Spirited Athletes in Professional Sports) Movement. Inside clubhouses, he scowled at teammates, reporters and club employees as if they were grime beneath his freshly manicured fingernails. On the field, he ignored 99 percent of fans who called his name, desperate for an autograph, a wave or even a simple nod. He treated his personal staffers like cockroaches and his wives like broken appliances.

His greatest failure came in response to the so-called waiter test -- How do you approach those individuals who you don't need? Or, as Curt Schilling recently told Dan Patrick about Bonds: "I just always had a problem liking people who treated people as less-than, as sub-humans. You want to find out about a player, talk to the trainers and the clubhouse guys. When you find players that treat those people like dirt, those generally tend to be the guys that are just bad people."

For 22 years, Bonds was a bad person. A terrible person. An absolute nightmare. Yet because he was The Barry Bonds, we all were required to kiss his feet, soothe his ego and carefully tiptoe toward his leather clubhouse recliner, where we would grovel for a moment's worth of attention (and, 99 percent of the time, be met with a swift, cold dismissal) in the shadow of his Jupiter-sized head.

Now, 2 1/2 years removed from his final game, Bonds finds himself justly submerged within a Twilight Zone plotline come to life -- To See the Invisible Man.

In that 1985 episode, a character named Mitchell Chaplin commits a crime and is sentenced to a year of being rendered invisible. No one talks to Chaplin, no one thinks of Chaplin, no one acts as if they see Chaplin. He is gone and forgotten; a distant memory that fades by the minute.

In short, Chaplin is in hell.

Now, so is Bonds.

For a ballplayer obsessed with his legacy, Bonds has no legacy. The once-vaunted all-time home run record? Insignificant and tainted by steroids. His Hall of Fame worthiness? A non-issue. With his performance-enhanced career, coupled with an attitude south of horrific, Bonds is voted into the Hall right after Moose Haas and Keith Garagozzo. His Q-rating? When's the last time you wore your No. 25 Giants jersey? His odds of being signed as a free agent? Zero. His odds of being hired as a major league coach or broadcaster? Zero. People in the game who truly like him? Zero. People outside of the game who truly like him? Zero.

Truth be told, his is the age-old story of the high school bully picking on the math wiz. "One day," the calculator-toting geek thinks to himself, "you won't be treating me this way. One day ..."

For Barry Bonds, one day has arrived. His wife Liz recently left him. His Web site, once the only way he would interact with the media, hasn't been updated for two months.

Of course, I only know this because, while writing these words, I took a moment to Google "Barry Bonds."

Otherwise, I don't care.