Junior was different kind of star

Ken Griffey Jr. retired last week, and I am still sort of sad.

Not because I wanted Junior to keep playing -- clearly, his skills had diminished to a Tim Tolman-esque level. And not because I'll miss talking to him -- our last conversation took place three or four years ago.

I'm sad about Junior's departure because, in the cliché-stuffed, sheep-mentality world of Major League Baseball, Ken Griffey Jr. was different.

Genuinely different.

When I picture Junior, I don't think about 630 home runs or 10 Gold Gloves or the backward cap or his slide across home plate to defeat the Yankees in the 1995 ALDS. No, I think about Joe Valentine, a dime-a-dozen right-handed reliever from Long Island, N.Y., who pitched 42 forgettable games with the Reds during the mid-2000s. I was working for Newsday at the time and approached Valentine for a local-kid-makes-good profile about his upbringing in the town of Deer Park. Amid talk of mitts and bats and fastballs down the plate, Valentine told me that he had been raised by lesbian parents -- not exactly the norm in the conservative clubhouse environs. The conversation inspired me to ask players about homosexuality, about the idea of possibly playing with openly gay teammates. The general reaction was revulsion: One pitcher memorably damned "those people;" a publicist for the Washington Nationals told me I was making his guys uncomfortable.

Then I approached Griffey. He was taken aback by the questioning, but not for the reasons one might think. "Wouldn't bother me at all," he said. "Not at all." He elaborated. "If I had a gay teammates, I wouldn't care even remotely," he said. "In fact, I'd embrace it. One of my closest friends in the world is gay; he comes and goes from my house without even knocking. It's just not a big deal to me."

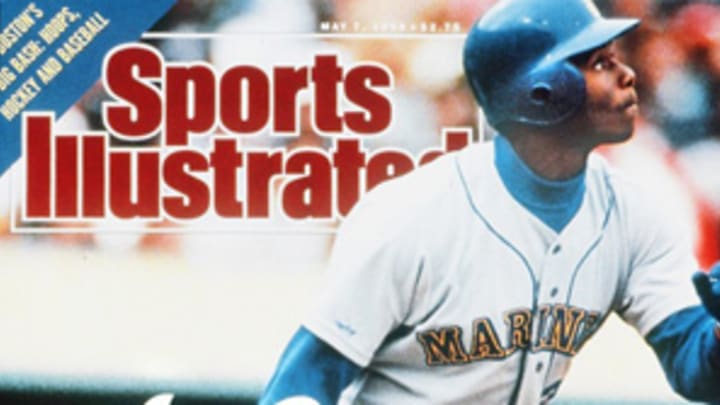

I've been told by many that the 19-year-old Junior who broke in with Seattle in 1989 was an awkward pain in the rear; a loudmouth egomaniac who needed to be the center of attention and was prone to slinging hurtful verbal insults. As Tyler Kepner eloquently wrote in Sunday's New York Times, "I have met few players as suspicious as Griffey, who greeted me with a sneer when I introduced myself as the new Mariners beat writer ... he promised me a year of initiation before he would trust me." This is not surprising: Rare is the bred-from-an-early-age-to-be-a-superstar superstar who winds up well adjusted. Think Willie Mays and Barry Bonds; think Lawrence Taylor and Todd Marinovich. Think about a kid, less than two years removed from high school, being hailed as the savior of a franchise and having a father with 2,143 major league hits of his own.

Impossible.

Griffey, however, defied the odds by genuinely evolving. Playing in the mid-major markets of Seattle and Cincinnati, he never openly pined for neither endorsements or more publicity. When steroid-enhanced cheaters like Bonds, Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa robbed him of much of his Q-rating and made his otherworldly stats seem pedestrian, Griffey refused to whine.

Junior was guarded, but also extremely funny. I was covering the Mariners 12 or 13 years ago when a man walked through the clubhouse with free sunglasses. Most guys accepted one pair -- Junior excused himself from a mini-press session, reached his hand into box and snagged a bunch. Then he looked at us, smiled and cracked, "If it's free, it's for me, and I'll take three!"

Back in the day I used to wear a sinfully ugly Kangol while covering baseball; my idea so ballplayers would remember me when I came back to town. The first time I met Griffey, during a spring training in the mid-1990s, he glanced my way and said, "Nice hat, guy." One year later, having not seen each other since, we walked past one another in a hallway. I had forgotten my beret at the hotel. "Hey," he said, "where's the hat?" I was stunned. Most ballplayers, any scribe will tell you, struggle to retain the names of the beat writers who cover them on a daily basis. Griffey met me once and recalled my hat.

I'd say 50 percent of the time I saw Griffey, he was with his children. Or talking to his children on the phone. Or telling funny stories about his children. Once, during a conversation at his locker at the Reds' old spring training compound in Sarasota, Fla., he whipped out a copy of the Orlando Sentinel and showed me a photo of one of his kids. "Cool," I said, completely serious. "How old is she?"

It was, in fact, his son, Trey. His hair had been braided.

There was an awkward pause, and then Griffey smiled. "No," he said, "that's my boy. He might wind up even better than me."

I laughed. "I doubt that," I said.

I doubt that.