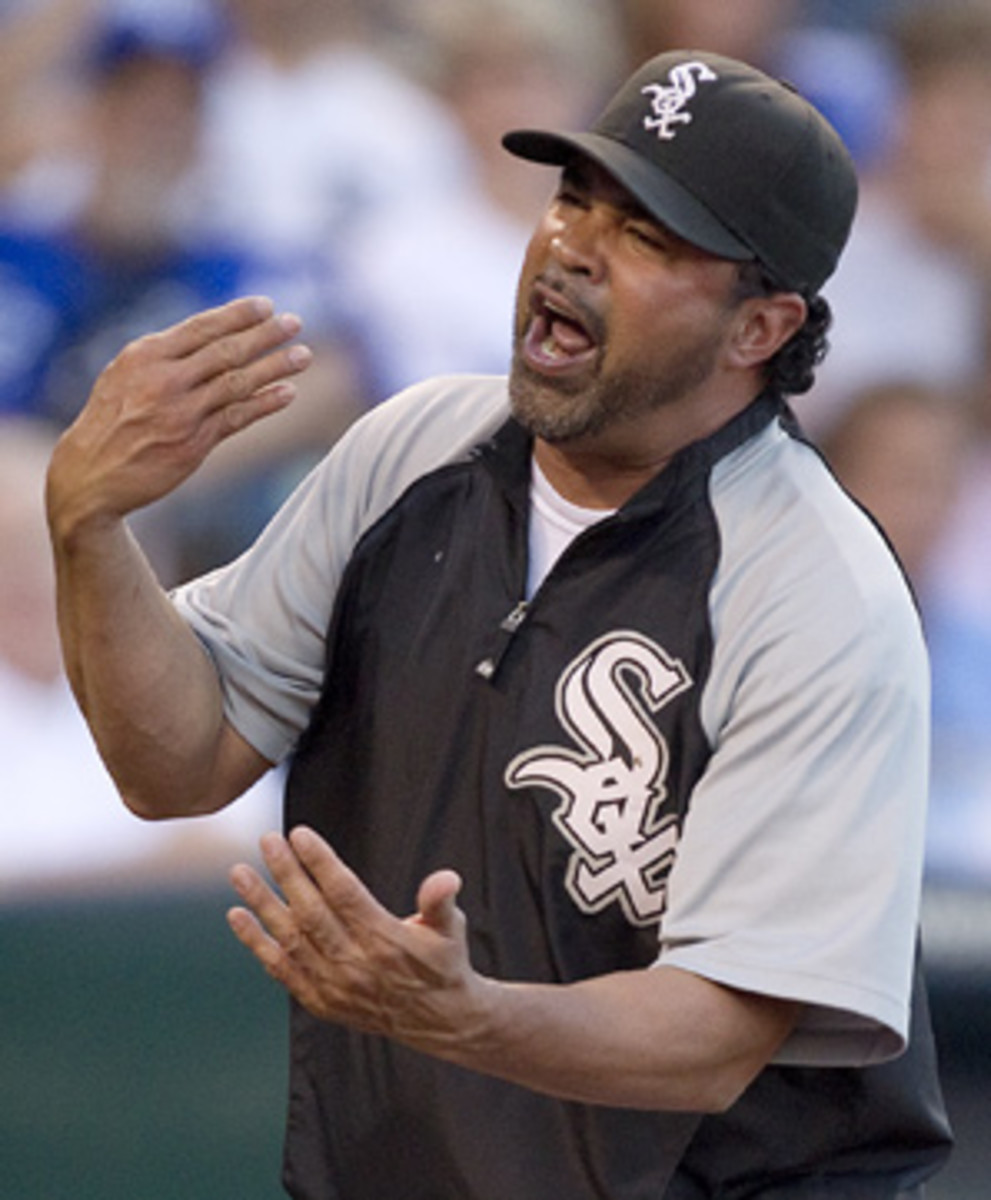

Ozzie's just being Ozzie

If you missed Ozzie Guillen's latest controversy, don't worry. In Chicago, Guillen controversies are like the L trains: if you miss one, you'll hear another one coming soon enough.

There was the time that Guillen, the White Sox manager, called umpire Joe West an bleep; and the time he called his former player (and fellow Venezuelan) Magglio Ordonez a bleep -- one of his favorite words is bleep, and he will use it to describe anything from a meal that is good bleep to a media member who is a total bleep; and the time he called columnist Jay Mariotti a bleep for never showing up in the White Sox clubhouse and saying Marriotti is "going to die as garbage"; and the many times he has said, in moment of crisis, that his team is playing like bleep and he can't believe he has to watch this bleep; and the time he said he might retire from managing if his White Sox won the World Series (they did; he didn't); and the time he said that Alex Rodriguez considered playing for the Dominican team in the World Baseball Classic because he is a "hypocrite" who was just "kissing Latino people's asses"; and the time, earlier this season, when he signed a baseball for an Indians fan that says "When are you going to win anything in sports? Please" ... we could go on.

And on.

And on and on.

Indeed, the amazing thing about Guillen is that he doesn't cause more controversies. His mouth starts so many fires it's like he spits gasoline. Take this latest rant, for example. Ozzie said Major League Baseball does not do as much for Hispanic players as it does for Japanese players, and this led to a side rant about Latinos and his efforts to educate them about performance-enhancing drugs. He has made these same points several times in the past. The national media just happened to pick up on it this time.

"Once, twice a month, you're going to have to deal with controversy, or some comment made by him or someone else in the organization," White Sox first baseman Paul Konerko said. "It's just part of the deal here. It's the way it is."

Naturally, Guillen has become known mostly for these controversies. He has been classified as a hothead or a clown. You might not realize what Konerko and most people who know Guillen say, unequivocally: You would like him.

People who are constantly getting into little spats tend to fall into one of two categories: they care too much about what other people think, or they don't care at all. Guillen doesn't care what people think. But he does care about people.

"He is really family-oriented," Konerko said. "If there is anything that comes up, even the slightest bit that has to do with wife or kids, he has no problem saying, just take a day off, do what you have to do. Those things pop up during the season. Even if it's a small thing, that always comes first."

Small things: The lineup card is always posted early in the White Sox clubhouse. Players usually know on Tuesday if they're playing Wednesday. This probably means nothing to you. But it matters to players, who build their workday around this information. You don't make it to your seventh year managing the same team unless players like playing for you.

Guillen goes ballistic if you show up late or don't play hard, but if you play a bad game, well, hell, he had a career on-base percentage of .287. He's played plenty of bad games.

"He understands: go out and give him what you have, and if it doesn't work out, let's have a few beers and we'll go get 'em tomorrow," Konerko said. "And if we win, let's have a few beers and go get 'em tomorrow. That's the drill, no matter what happens, as long as you're giving 100 percent."

When the Sox lose, Guillen is often the one who puts on the music in the clubhouse afterward. Konerko says they even appreciate that he is such a magnet for the media, because this means the players mostly get left alone.

"I don't think it's anything calculated about the team," said Konerko, who admitted he didn't really know what Ozzie had said this time and wasn't in any hurry to find out. "I just think the questions come, and at the right time or the wrong time, he just answers how he answers. I don't think he sits down and says, 'We're on a four-game losing streak, let me talk about this so it becomes a big story.' ... There are a lot of managers out there who don't say anything and are bad to their players. You'll never know who those guys are. So I'll take what we have."

In the visiting manager's office at Detroit's Comerica Park this week, Guillen had one request: go back to the beginning. He meant we should listen to his whole rant, in context, from the beginning. Somebody had asked Guillen about his gifted young Cuban infielder, Dayán Viciedo. Guillen tried to explain that Viciedo faced so many challenges besides opposing pitchers -- he is learning a new language, and living in a new culture, and virtually everything in his life has changed. And he doesn't have the advantage of his own interpreter, as many Japanese players do.

That, Guillen said, was his whole point: it's hard for Viciedo. And frankly, if he had just left Japanese players out of it, this would not even have caused a ripple. It was the comparison that got to people. Americans recoil at the notion of playing racial favorites (even though Guillen says that was not what he meant).

But let's take Guillen more literally than that. Let's go back to his beginning. Guillen was a high school dropout in Venezuela. Major League Baseball casts a big net through the Caribbean and Central America, and Guillen jumped in it -- as he said this week, the Latinos shouldn't really complain, because "we choose to go."

They're all chasing a dream. Most guys don't make it. Guillen did -- despite limited skills, by Major League standards, he played nearly 2,000 games in the big leagues. He has spent 25 years shuttling between worlds -- from the fame and wealth of Major League Baseball to the dangerous, poverty-ridden streets of Venezuela, where kidnappings for ransom have been a serious problem for years.

Everything he says falls in the gap between those two worlds. There is nothing in Major League Baseball that can scare him silent, and nothing that will make him forget all those guys in Venezuela who jumped in the net and didn't make it. He could have made a better choice of words this week. He could do that a lot of times. But he will always choose words over silence.