Inside look at NCAA enforcers who are spearheading AgentGate

INDIANAPOLIS -- At first, Marcus Wilson thought it was really cool when a prominent sports agent came to speak at one of his law school classes. He had seen Jerry Maguire. He thought he might want to join the profession. So the former North Carolina football player approached the agent after class to ask if he might shadow him for a day.

"He actually asked me to be a runner for him," Wilson said. "He said, 'I'm trying to recruit a player at your school. You know him. Can you get me his telephone number?' "

Today, Wilson is in the agent business -- the business of busting them, that is. Following two years as a prosecutor, Wilson joined the NCAA's Agent, Gambling and Amateurism Activities division in 2008. The four-person group -- composed of director Rachel Newman-Baker, 33; associate director Angie Cretors, 33; and assistant directors Wilson, 29, and Chance Miller, 27 -- has spent much of its time flying to campuses around the country spearheading a slew of highly publicized investigations into players receiving extra benefits from agents and their recruiters.

"I had a flight attendant ask me the other day if I worked for the airline because she'd seen me on the flight so many times," Miller said.

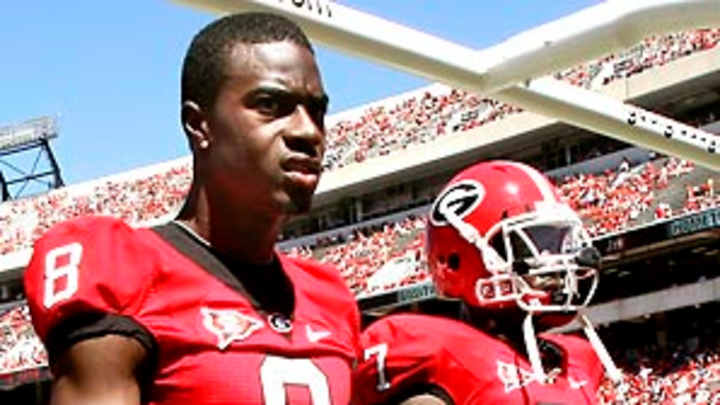

The division's work to date has resulted in early-season suspensions for several high-profile players at North Carolina (among them defensive tackle Marvin Austin and receiver Greg Little), Georgia (receiver A.J. Green) and Alabama (defensive end Marcell Dareus), while South Carolina tight end Weslye Saunders, also under investigation, was dismissed from his team on Wednesday for undisclosed reasons. North Carolina associate head coach John Blake, believed to be a subject of the probe in Chapel Hill because of his reported relationship with NFL agent Gary Wichard, resigned last Monday. (Due to conflict of interest, Wilson has not conducted the UNC inquiry.)

On the heels of NCAA sanctions at USC, where former star Reggie Bush accepted benefits from a trio of sports marketers, AgentGate -- as the summer's confluence of headlines became known -- has elicited national debate over a long-dormant issue. Nick Saban famously called agents "pimps" at SEC Media Days and organized conference calls with NFL officials to discuss the issue. Various agents fired back in defense of their industry. Some lauded the NCAA for finally "getting tough" about agent rules. Others wondered why it took this long.

Newman-Baker, whose 10-year-old group operates within the NCAA's larger enforcement division, appreciates the increased awareness caused by the current cases, but laments the perception that the NCAA is only now becoming vigorous about agent-player activity.

"People on the outside ... don't know all that we do behind the scenes," Newman-Baker said. "They read about the one case that's in the paper, but they don't know Marcus has spent the past two years developing a relationship with Agent X so he can connect a whole bunch of dots, or Angie has spent every July in every basketball gym that all the major coaches go to.

"These guys work their tails off. They truly care about what they're doing. They put up with a lot. And they don't get paid a million-dollar salary to do what they do."

On a rare, recent afternoon when all four were in one place, the AGA staffers sat around a conference table at NCAA headquarters in Indianapolis and discussed the rewards and frustrations of their seemingly impracticable job -- one that involves policing thousands of college athletes and the untold agents, runners, handlers, sports marketers and financial advisors who try to recruit them. (By NCAA rule, they were not allowed to discuss specific athletes or investigations.)

Wilson, Cretors and Newman-Baker (Berea College basketball) are themselves former athletes. Miller and Wilson both have law degrees, while Cretors (Kansas) and Newman-Baker (Ohio State) previously worked in athletic departments.

"I'm very passionate about the principle of amateurism," said Cretors, an AGA staffer since 2003 who interviewed key witnesses in the USC/Bush case. "A lot of people in the general public laugh at it when you talk about the big sports, but I genuinely think [amateurism] is the bedrock of intercollegiate sports, which includes the agent component."

Newman-Baker, who joined the group as an intern in 2001, agrees: "All of us believe that most of the life lessons we learned [in college] came from our experience in athletics, and in all of our situations, it truly was the 'student athlete.' To kind of carry that over into what we do on a day-to-day basis, that background and that passion helps you."

Her team needs all the help it can get, because the AGA is extremely limited by both numbers and lack of jurisdiction. With no subpoena power over non-university personnel, leads and cases often hit dead ends. And while the NCAA enforcement model relies on schools to self-police, Newman-Baker said agent violations are rarely self-reported.

"Institutions want to do it," she said, "but I'm not sure they necessarily know what they're looking for."

By Newman-Baker's own admission, it has taken years of networking and cultivating sources within both the pro leagues and the agent community for the AGA to make headway. (It's believed that rival agents of the perpetrators were among the NCAA's main informants regarding the much-chronicled South Beach parties to which many of the recently suspended players were tied.)

"We're not going to completely eradicate [the problem]," Newman-Baker said. "I don't think that's anyone's expectation. More than anything, the message we want to send is, 'If you're doing it now, we are going to know about it, and we are going to follow through with it.' We want to establish something of a healthy fear out there, because quite frankly, I'm not sure that's always existed."

Others remain skeptical that current methods can make a real impact, however.

Rand Getlin, whose company, Synrgy Sports, provides agent-education assistance for college athletic departments, believes that no real change will come unless state and federal authorities begin prosecuting unethical agents. (An Associated Press review found that more than half of the 42 states with sports agent laws have yet to revoke or suspend a single license, though North Carolina Secretary of State Elaine Marshall recently launched an investigation.)

"If you talk to any agent, they know how dirty [the business] is," Getlin said. "But the AGA is one group. It's a noble pursuit, but without the help of federal governments and state governments, and the subpoena power they hold, to what extent are they really going to root it out? No matter how hard they work -- 20-hour days, sleep under their desk -- there's no possibility they could stay on all this stuff."

Newman-Baker said the group is starting to find parties more receptive to offering assistance. On Aug. 16, the group participated in a teleconference with representatives from the NFL, NFL Players Association, American Football Coaches Association and individual agents to "identify points of collaboration and potential solutions." Another call is scheduled for later this month. Alabama coach Saban had earlier organized a series of related calls involving his fellow coaches (among them, Florida's Urban Meyer and Oklahoma's Bob Stoops) and NCAA and NFL officials.

"It's a tough deal, because you first have to find out about something, and then you have to prove it, which isn't always the easiest thing to do with the limited resources the NCAA has," said AFCA executive director and former Baylor coach Grant Taeff. "They get a lot of criticism, but I've watched them over the years, and they consistently do a very good job."

Meanwhile, the Division I Amateurism Cabinet began discussing agent oversight at its June meeting. Some have called for a complete overhaul of prevailing NCAA agent rules, perhaps even allowing for athletes to seek counsel from agents while still in college. But that wouldn't necessarily preclude players from taking handouts.

"The issue of how to get proper information in front of the student-athletes is one that is being discussed by a lot of people in the national office and the membership now," said David Price, the NCAA's vice president of enforcement. "There are various suggestions that are being considered. But don't confuse it with the issue of them providing benefits. There are some issues you have to deal with from a practical standpoint when you open up complete access to agents."

The problem, said the staff members, is that much of the illicit activity being brought to their attention takes place long before a player actually needs an agent -- and doesn't necessarily involve actual agents. For example, while ChrisHawkins, whose purchase of Georgia wide receiver Green's game-worn jersey for $1,000 resulted in the player's suspension, is not a registered agent, he befriended several current UNC players in an apparent attempt to "shop" them to potential agents, according to an ESPN.com report.

"What we're seeing is these financial advisors, marketing reps -- people that don't have any governing body -- are the ones going in before the [NFL's] 'junior rule' takes effect," Wilson said. "They're the ones making initial points of contact."

AGA staffer Miller identified the same problem: "You also see the third parties that aren't attached to a certain agent or financial advisor that latch on to these kids in high school. They take care of them, then once they're in college, they stay latched on to them and they start reaching out on their behalf to try to look for agents and financial advisors. You start to see the same people within certain cities."

Because of the nature of most first contact, the staff spends an inordinate amount of time processing minor cases involving secondary violations such as an agent's paying for a player's meal.

"One of the easiest ways to make that initial contact is to add [the player] as a friend on Facebook, initiate a chat, introduce themselves," Wilson said. "They'll say, 'Oh, by the way, I'm going to be on your campus in a couple of weeks. You want to meet up for dinner and we'll talk about your draft projections?' ... We have these cases every year that involve meals at a restaurant."

There is an obvious source of help for the AGA's staffers: adding more colleagues.

"How many millions of dollars does the NCAA oversee, and they're supposed to be the gatekeepers for all of amateurism?" Getlin said. "Four people?"

Price's enforcement division recently gained three staffers to focus on basketball issues, raising its total number of investigators to 23, but despite the current spotlight on agent issues, there are no plans to expand the AGA.

Until that changes, Newman-Baker, Cretors, Wilson and Miller will keep racking up frequent flier miles and hotel points in the hopes of nailing another case.

"We're not out looking to ruin kids' careers and lives," Cretors said. "There are some cases where you genuinely feel bad for a kid who might have been taken advantage of. But then you look at the other 300,000 student-athletes who are doing it right, who weren't getting the same benefits. It may sound Pollyannaish, but ..."

But they believe in it.