The steroid Hall of Fame debate

Innocent until proven guilty.

That's what they maintain. All of them. The baseball players. The majority of baseball writers. The bloggers. The foaming-from-their-mouths fans, many of who sit and wait by their Twitter accounts, anxious to destroy anyone who dares to question the Hall of Fame worthiness of a superstar ballplayer from the so-called "Steroid Era."

"I require a bit of evidence before I accuse someone of wrongdoing," NBC Sports' Craig Calcaterra wrote recently, "and refuse to honor their career in a way it should be honored."

It is, constitutionally speaking, a sound point of view. We live in a nation where -- rumor has it -- all citizens are supposed to be presumed clean until evidence shows otherwise. Many have argued it to be America's greatest virtue; in this country, you cannot be punished for the mere presumption of guilt.

There must be proof.

What happens, however, if proof is impossible to ascertain? More to the point, what happens if proof is impossible to ascertain because the alleged guilty (and those working on their behalf) have made it so? What if there is no such thing as proof? What if it is as tangible as Roy Hobbs and the $3 bill? What if it can never actually exist?

Until 2004, Major League Baseball did not test for performance-enhancing drugs. This wasn't because the available methods weren't accurate enough, or because the timing wasn't right, or because Bud Selig was on a lengthy vacation to Guam. No, the reason Major League Baseball did not have a testing policy was because nobody within the game wanted players to get caught. Thanks in large part to the pervasive usage of steroids, growth hormones and other performance-enhancing drugs, baseballs were soaring out of stadiums in record numbers. There was the magical Sosa-McGwire home run chase of '98. There was Barry Bonds hitting 73 in 2001. There was Rafael Palmeiro and Jose Canseco and Jason Giambi and Jeremy Giambi and, well, the list is endless.

For the corporation known as Major League Baseball, power equaled a post-'97 lockout return to packed stadiums, and packed stadiums equaled money, and money equaled happy owners. For the juiced players, power equaled inflated numbers, which equaled inflated contracts.

So, until pressure came along, the owners did nothing.

The players said nothing.

The union -- specifically Donald Fehr -- fought to keep nothingness the norm.

Then one day, against the initial wills of everyone employed by the game, genuine testing for PED began.

And here we are.

Because baseball lived in a self-imposed state of (public) denial for so long, the standard of innocent until proven guilty cannot be applied to the current Hall of Fame ballot. It can't apply in 2011, either. Or 2012. Or 2013. Or 2014. Or ...

Simply put, if there is no chance of guilt -- if it is a literal impossibility -- what is the value of such an ideal? "People say, 'Hey, this guy never failed a drug test,' as a defense of certain players," says Howard Bryant, an ESPN.com senior writer and author of Juicing the Game. "It's an intellectually lazy argument. Generally speaking, innocent until proven guilty is true. But how can you use the never-failed-a-drug-test argument when, until relatively recently, there was nothing to fail?

"When we in the media were trying to prove what was going on, we kept hearing the he-didn't-fail-a-test point made over and over. Then, when things started to come out with BALCO and Jose Canseco and the congressional hearings, those same people were asking 'Why can't we just move on?' They want it both ways. And now that everyone has steroid fatigue, they want to pretend it never happened. Bad news -- it did."

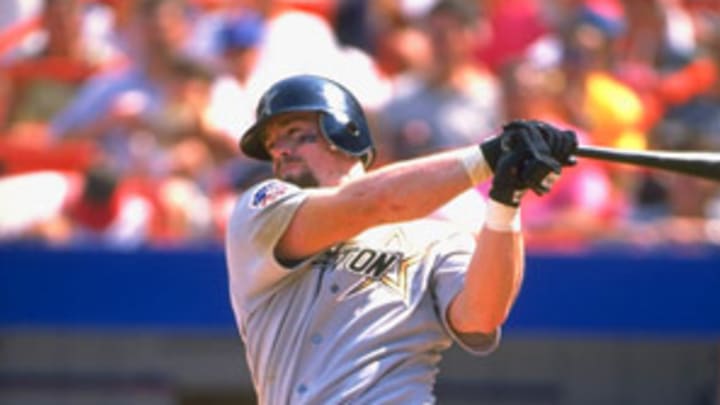

Among the current nominees for the Hall, former Astros slugger Jeff Bagwell finds himself facing the most PED-related doubters. A handful of media types (and I have been among them) cite his staggering power numbers, his Randy (Macho Man) Savage physique as a player (as opposed to his Screech Powers physique as a retiree), his many years with a franchise that, inside the game, was known to be a hotbed for steroids. When I recently called a former Major League contemporary of Bagwell's to ask if one was right to question to four-time All-Star, he laughed. "Absolutely," he said.

Does this mean Jeff Bagwell used steroids? No, it doesn't. As NBC Sports' Calcaterra rightly pointed out in a recent post, "There is just as much evidence against [stars like Derek Jeter, Cal Ripken Jr., Randy Johnson, etc.] as there is against Bagwell." Again, the problem with the flawed logic of Calcaterra (one of the leaders of the leave-these-poor-guys-alone movement) and his minions is: There is no evidence. Against anyone. Because baseball made certain of it.

This is not to say Hall of Fame voters shouldn't support Jeff Bagwell. Or should support Jeff Bagwell. What it means is that, thanks to Major League Baseball's defiant stubbornness throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, when guilty vs. innocent was rendered nonexistent, voters have the right to rely on their suspicions.

Is it an arbitrary system? Yes. Will it inevitably punish the innocent? Probably. Does the Hall need to consider tinkering with its eligibility guidelines? No doubt. (Says Bryant: "Baseball is incredibly cowardly on this subject. They gave us a road map on Pete Rose and on the Black Sox. But they can't give us one here? Why not?")

Is there anything we can do about it right now?

Sadly, no.