Historic comeback only part of why '78 Yankees were so memorable

Back in January, New York magazine, the arbiter of all matters Gotham, declared 1978 to be among the city's five "Greatest Years" . . .ever. Seriously. One of the reasons: "You could go watch the terrific circus up at Yankee Stadium for just $2.50 and buy your ticket at the window on your way in." Well, they sure got the Yankees part right. I know because, as a Sports Illustrated baseball writer, I had a ringside seat with backstage access.

In 1978 the Yankees came from 14 games behind Boston to win the AL East, then won their third straight American League pennant and second straight World Series. They were a writer's dream team of great pitching, timely hitting and clashing egos. They had a Machiavellian owner, a mean-spirited manager and a misanthropic captain. The main attraction was the self-described straw that stirs the drink, Mr. October himself, Reggie Jackson. The rest of the team? Fine fellows and accomplished performers, but not always consumed with riding atop the elephant.

I wrote more Yankee stories from 1976-78 than letters home: 12 overall and seven in '78 alone. In 1976 I profiled catcher Thurman Munson after penetrating his sour disposition. By reminding him that SI coverage could only help his Most Valuable Player candidacy, he finally let me into his insecure world. After a game in California, he even invited me to join him and a special friend with a Dunhill lighter for dinner, as long as I didn't mention the special friend. The story ran, no secrets were revealed, and Munson won his well-deserved MVP award.

Early in the 1977 season another assignment took me to the altar of Jackson, New York's newly signed free agent superstar. Getting his interest and attention was a little -- no, a lot -- easier. "Reggie. . .," I said to him in the Yankees' clubhouse. He ignored me. "I'm Larry Keith. . ." He ignored me. ". . .of Sports Illustrated." Whereupon he stopped abruptly, put his arm around my shoulder and inquired cheerfully, "What can I do for you?" Informed that the magazine was considering a cover story on his Cleopatra-like arrival in New York, he immediately led me into the team's training room to talk. The room was verboten to writers, but Reggie didn't care. Later, while looking for two seats on the team airplane so we could continue our interviews, he told one poor fellow to get up and move to another row. And as if to emphasize his Reggieness, he pulled out a huge wad of cash for all to admire. Classy. The following week's cover story asked "Can Reggie Jackson Find Love And Happiness In New York?"

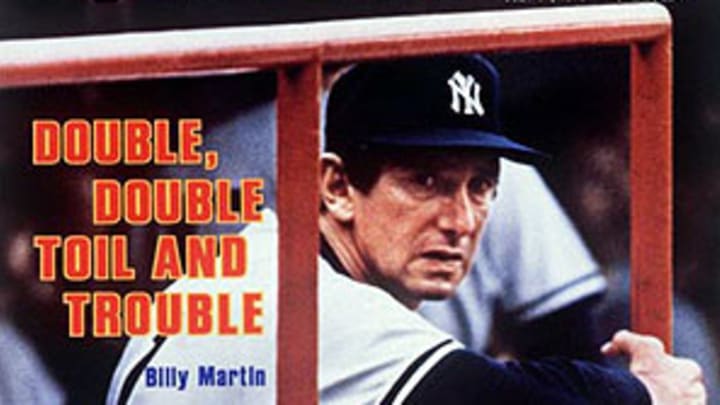

As long as Billy Martin was the manager, the answer was decidedly no. Their egos couldn't occupy the same airspace. Later in 1977 they had to be restrained from getting at each other in the dugout during a game in Boston. Then on July 17, 1978 another incident occurred that reordered the Yankees universe. In the 10th inning of a game against Kansas City, Jackson petulantly defied Martin by attempting to bunt. Jackson made an out, and the fourth-place Yankees suffered their third straight loss to fall 14 games behind Boston.

The Yankees sent Jackson off on a five-day suspension, and the magazine sent me off to Chicago to assess the fading champions and await the prodigal son's return the following Sunday. I was particularly anxious to speak to Martin, and, despite his sullen and suspicious nature, he was more than obliging, inviting me (well, not me, personally, so much as my Sports Illustrated credential) to join him for drinks. He unloaded on both Jackson and owner George Steinbrenner, reminisced about his halcyon days as a Yankee player and half-seriously suggested we might do a book together some day. Sure, fine. All I wanted was access and insights for that week's story, and he was generously providing them.

Jackson clearly enjoyed being in the middle of the media tsunami that welcomed his return from Elba. Martin didn't like it at all, and he refused to reinstate him to the lineup. After the Sunday game, I finished my story and sauntered down to the manager's office. He was preparing to leave for the airport, fuming about Jackson and seething over a rumor that earlier in the season the Yankees had talked to the White Sox about a managerial trade for Bob Lemon. Frustrated, hurt and angry, he let loose against the men he considered his biggest antagonists: "They deserve each other. One's a born liar, and the other's convicted." (Steinbrenner had pleaded guilty in 1974 to illegal campaign contributions and obstruction of justice.)

This is where I should have pulled out my cell phone -- well, rushed to a pay phone -- called the magazine, and reprised the classic B movie newspaper line, "Hello, sweetheart, get me rewrite." But I didn't. I wrongly assumed that Martin's diatribe was off the record, fueled by his dark disposition. He had already told me that publicly criticizing the meddling owner would cost him his job and that he couldn't afford to be fired. He knew I had filed my story, so it was past deadline in his mind. Billy the Kid was just letting off steam to a recent drinking buddy. Or so I thought.

I flew back home to New York feeling very proud of myself, when one of the magazine's assistant managing editors, Jerry Tax, roused me from my well-earned sleep the next morning to report that Martin was going to be fired for something he had said the previous afternoon about Jackson and Steinbrenner to two New York sportswriters at O'Hare airport: "They deserve each other. One's a born liar, and the other's convicted." Funny thing about that quote, Jerry, I began to explain...

I rushed to the office to rework my story and began by calling Martin at the team's Kansas City hotel. He told me that Yankee president Al Rosen was on his way, but that it didn't matter because he had decided to quit. And one other thing: "I didn't say what the newspaper said." When I reminded him that he had given me the same quote on the previous afternoon he insisted, "Well, I didn't say it to them." Of course, he had, and though he denied it again at his resignation press conference, he ultimately admitted the truth. The season became even more surreal a few days later when the Yankees introduced fan-favorite Martin to a packed house and said he would return as manager in 1980. Lemon had succeeded Martin after all but would only be an interim.

SI VAULT:A bunt that went boom! (07.31.78), by Larry Keith

The old Indians Hall of Fame pitcher inherited a team desperate for mental and physical repair. For most of the season, they were dead. Deader than a door nail, as Dickens wrote of Marley. And being dead they didn't have a ghost of a chance. "We were flat out of it," DH/outfielder Lou Piniella would admit to feeling later. "Optimism can only take a team so far."

The first indication that the season might not go exactly as planned occurred on Opening Day in Texas. During the winter, Steinbrenner had signed Goose Gossage, the erstwhile best reliever in the National League, to disenfranchise the best reliever in the American League, reigning Cy Young winner Sparky Lyle. ("Cy Young to sayonara," as third baseman and resident wit Graig Nettles memorably put it.) In his maiden appearance, Gossage gave up a game-winning homer. Uh, oh, bad omen.

And so the next few months unfolded with low performance and high drama, with injured players and hurt feelings, with contretemps in the newspapers, the clubhouse and on an airplane, as none other than Cap'n Thurman, himself, became one of several malcontents who refused to play out of pique at one time or another. He wanted out altogether, and so did some others.

But when Martin left, the turbulence calmed and the clouds lifted. Under Lemon, the rejuvenated Yankees finished in a 48-20 flourish that included their first four-game sweep at Fenway Park since 1949 that was so thorough it was dubbed the Boston Massacre. Happier, healthier players surely helped, but Lemon wryly noted that the New York newspaper strike that kept the Yankee sniping off the back page of the tabloids "did more for us than if we picked up a 20-game winner." Actually the Yankees already had two, spectacular Cy Young-to-be recipient Ron Guidry and Ed Figueroa. They also got a big boost from Catfish Hunter, who disproved reports of his early demise to win 10 of his last 13 decisions.

SI VAULT:Dear Billy: You Won't Believe What You've Missed (09.25.78), by Larry Keith

Where was Mr. October in all of this, you're wondering? In 1978 he was playing shortstop. Even before his heroics in the one-game tiebreaker against Boston, Bucky Dent had said the Yankees' resurgence "means a lot. Now people can respect us for the way we play, instead of thinking we're some kind of soap opera." So it was especially nice that the teen idol, a frequent pinch-hit target, would set things right, first by stroking the home run into the Fenway Park netting in Game 163 that sent the Yankees to the postseason and then becoming the World Series' Most Valuable Player by hitting .417.

As the engraving inside the team's gold and diamond championship rings would attest, the 1978 Yankees had accomplished the GREATEST COMEBACK IN HISTORY. Perfectly appropriate for The Greatest Show on Earth.