Memo to owners: spend money!

Three weeks ago, when the news broke that Tigers' DH Victor Martinez had injured his knee and could be out for the season, it created a window. The Tigers' offense, so reliant on just a few hitters in 2011 when Detroit won the AL Central, would be down a big piece in 2012. There was an opportunity for an up-and-coming team like the Royals, set on offense but with a questionable rotation, to step into the vacuum and close the gap on the top of the division by signing an available free-agent starter such as Edwin Jackson or Roy Oswalt. That kind of aggressive move could have turned the division race into a coin flip.

We know what happened next. The Royals did nothing while the Tigers replaced Martinez with Prince Fielder at a cost of $214 million over nine years. The swift, even shocking, speed of the signing was a credit to Tigers' owner Mike Ilitch. Ilitch, 83, is committed to bringing a World Series title to Detroit, and to that end has allowed GM Dave Dombrowski to sign free agents, pursue "unsignable'' draftees and push the Tigers' payroll to one of the top ones in the game. The Tigers are one of just four teams to ever pay MLB's luxury tax (in 2008), and the team's 2012 payroll may exceed $130 million for the third time in five years.

Ilitch represents an approach to sports-team ownership that is in short supply these days: wanting the next win more than the next dollar. Far too many franchises are run as if they're the corner grocery, with the need to stay in the black for the next month, next quarter, next year the primary goal, and winning a secondary one.

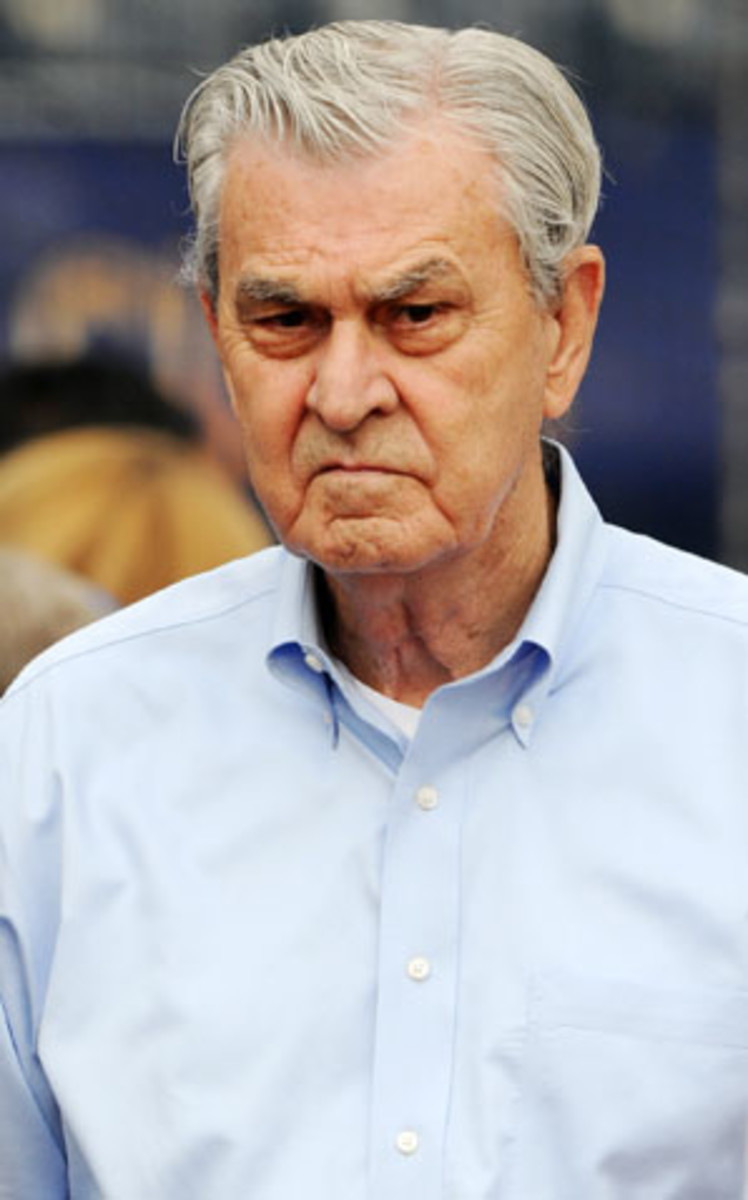

Contrast Ilitch to David Glass, the Royals owner. Glass has, since taking over the Royals in 1993, consistently been a hawk on labor issues, pressing for his Royals to get more of the money generated in other places, but rarely putting any money generated anywhere into the team. In recent years the Royals have spent a bit more in the draft and in international amateur signings than they had, but their approach to building the MLB roster remains penurious at best. Three weeks ago, Glass could have written a check that made the Royals three, maybe four wins better by signing Jackson, who would have immediately become the team's best starting pitcher. The Royals have an exciting young lineup and a strong bullpen, as well as young starters who may not be ready in 2012. Adding Jackson to the mix to challenge a Tigers team reeling from the loss of its DH would have cost nothing but money and made Kansas City better.

Glass though, represents that other, more common strain of ownership, the one that refuses to make investments that could potentially put the team in the red. The Kansas City Royals, like the other teams in the smallest markets in baseball, collect money from ticket sales and local media rights. They also get equal shares of nationally generated revenue, such as for Sunday Night Baseball or the postseason or the All-Star Game, even if they rarely if ever show up in those slots. On top of that, they get free money just for existing. Yet the Royals' 2011 payroll (just north of $38 million, according to Cot's Contracts) was lower than it was in any year since 2005, low enough to nearly guarantee a profit if no one showed up at the park.

The conversation about these matters tends to use a language --- "what we can afford", "in our market", "fiscal responsibility" -- that clouds what is happening, which is that spectacularly wealthy men, women and companies can invest in their product, but they often choose not to. The fact is, everybody who owns a major league team -- when MLB isn't making spectacularly bad choices about who gets to own a team, anyway -- is wealthy enough to make investments in the product that can improve the win-loss record without sweating whether the team will have positive cash-flow in the short term. The financial benefits of talent investment tend to accrue in future years for one -- a good team in Year One brings people to the park in Year Two, and so on -- while every team appreciates over time.

According to Forbes, Mike Ilitch was worth $2.7 billion in 2010, money he made by starting a popular national pizza chain and growing from there. David Glass' fortune is harder to pin down, but one estimate that dates to 1999 pinned it at $323 million, and it's not like Wal-Mart, for whom he used to be CEO, had a bad decade. You can do this with other owners, too - the Pirates' Robert Nutting and the Blue Jays' Rogers Corporation and the A's Lew Wolff and the whole lot of them.

These are incredibly rich entities who have competed aggressively and successfully to build their businesses. So why is it when they get into sports, all they want to do is talk about how they can't compete and need help from their competitors to make money? David Glass was the CEO of Wal-Mart, the most vicious competitor on the American landscape, but in baseball he can't spend a dime unless the Yankees give him six cents? That's not just disingenuous, it's a little bit pathetic.

We should demand more. We should hold up Mike Ilitch as the model, and we should rain scorn down on these rich men who hold fan bases hostage because they can't get a new ballpark or a new city or a new CBA to make their incredibly profitable long-term investments that much more profitable in the short term.

Owning a baseball team isn't like owning a conventional business, because there are benefits that accrue to baseball owners, a status that attaches to them in the community, that you don't get by being the most respected man on the Chamber of Commerce. Let's stop pretending that in exchange for that status, these men have no responsibility to the people who bestow it upon them.

We need more owners who want the next win more than the next dollar.