For better or worse, goats an indelible part of sports culture

He went in as the prospective G.O.A.T. and emerged as the presumptive goat, but what Tom Brady really is after Super Bowl XLVI is a living testament to the human need -- embedded in the race -- for individual scapegoats.

While the name of the Super Bowl goat changes hourly -- Brady? Belichick? Bundchen? -- the name is hardly important. But history does demand that the role be filled. The Giants' Ahmad Bradshaw was somehow fitted for goat horns after scoring what proved to be the Super Bowl's game-winning touchdown. In retrospect, Patriots' coach Belichick became a possible goat for allowing Bradshaw to do just that. As for the game's biggest hero, Mario Manningham -- Goat is his middle name. (Or very nearly so: It's Cashmere.)

This goat business can get confusing, but suffice to say that the star of every game requires an anti-star. (The reverse holds true as well. No goats, no glory.)

Here's how it works: Sometime after the conclusion of a Super Bowl -- and often times before then -- a consensus of international press, spectators and social media torchbearers will select its sacrificial goat. That goat is then fed into the vast, virtual spanking machine of the Internet, after which there is no turning back. The goat must be rendered into goat milk, goat cheese, goat's-head soup and other goat products. Creating a goat is the only way to expiate a team's sins and it has always been so.

In Biblical times, on the Day of Atonement, one goat was slaughtered while a second goat was exiled to the desert. This escaped goat -- this scapegoat -- carried the community's sins away with him, a rite of purification that individual athletes now perform, however unwillingly, in Super Bowl losses and World Cup finals and other secular spectacles of the 21st century.

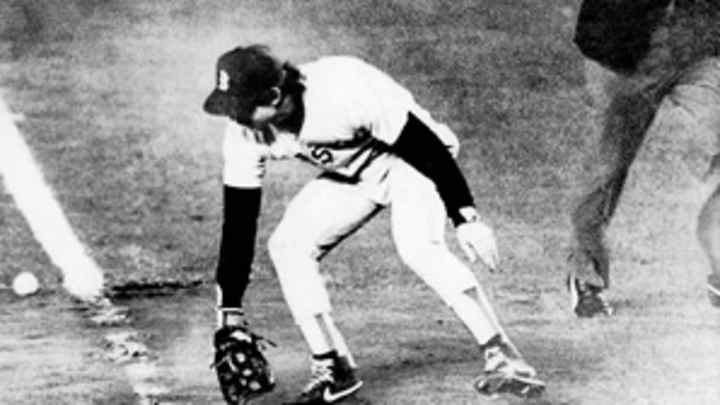

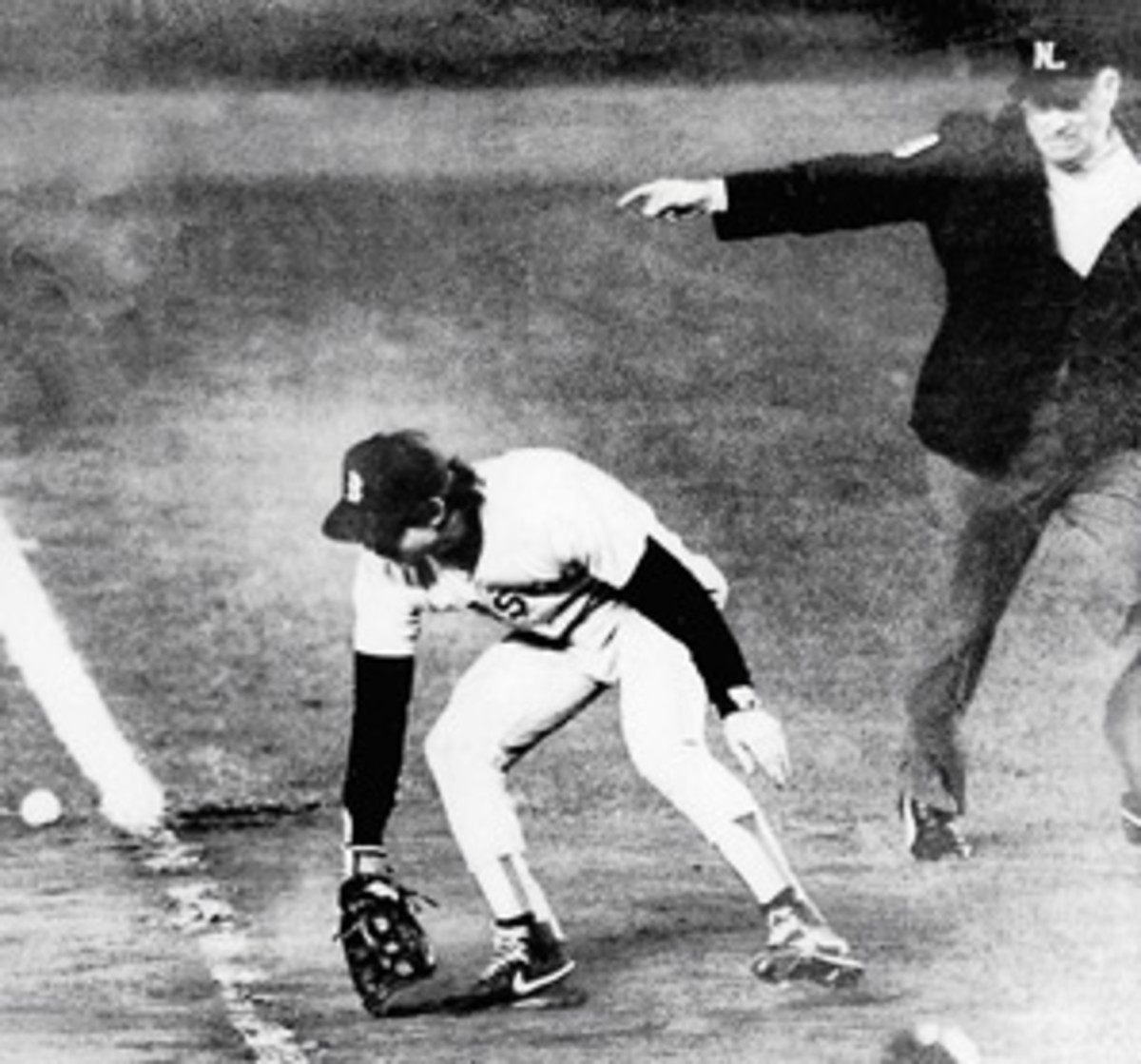

Among scapegoats, Bill Buckner is the Greatest Of All Time -- the G.O.A.T. of goats -- which explains why my one encounter with the Red Sox first baseman was in the Arizona desert. (Albeit one with a golf course.) This goat was literally living in exile, Old Testament-style. Buckner admirably bore his burden for 18 years -- the average life span of an actual goat -- until the Sox won the 2004 World Series under manager Terry Francona and general manager Theo Epstein. After winning another World Series, the pair was scapegoated themselves, last September. Epstein was exiled to the Chicago Cubs, who haven't won a World Series since 1908, cursed as they are by a vengeful billy goat.

In short, the goat is and always has been a powerful symbol of bad mojo. Sheep are kind and innocent and easily led astray. On the sideline in Indianapolis after his premature touchdown, Ahmad Bradshaw looked sheepish rather than goatish, which has an altogether different association of lechery. Goats are horny in both senses of the phrase, which is why the devil -- as depicted in cartoons and Halloween costumes -- always wears horns and hooves and a pointy beard. That beard is more commonly called -- sigh -- a goatee.

None of this is remotely fair to all of goatkind, of course. For every "Murphy" -- the billy goat from the Billy Goat Tavern who cursed the Cubs in 1945 -- there is a "Bill the Goat," the upstanding mascot of the U.S. Naval Academy who is nevertheless a frequent victim of unjust goatnappings.

In much the same way, scapegoating of human beings is unfair and entirely unnecessary. In our popular imagination, Super Bowl goats tend to go silent (like Scott Norwood) or crazy (like his fictional doppelganger, Ray Finkle, in Ace Ventura: Pet Detective). What scapegoating does to the rest of us -- we, the goat-makers -- is another question entirely.

The Greek god Pan was half man, half goat. His horns and hooves and human torso instilled fear in crowds. It is from Pan that we get the word panic, the irrational mass hysteria that leads humans to do destructive things. Like, for instance, singling out the individual: It satisfies our appetite for blame while absolving everyone else of guilt, ourselves included. Scapegoating Tom Brady is a form of mass hysteria, spread tweet-by-tweet, street-by-street, one dimwitted analyst to the next.

This is not the fault of any one person. Scapegoating has no scapegoat. It's what we all do. It has become the job of every modern sports fan and pundit: Conspicuous finger pointing, with a giant index finger made of foam.