Memories that last forever

This column was adapted from an essay that runs in the May 14th, 2012 issue of Sports Illustrated. Purchase the digital edition of the magazine here.

What if, decades after the fact, someone decided to write a book about what you consider your greatest -- or worst -- high school sports moment? How much importance would you attach to the event? How, if at all, would it still define you?

The e-mail arrived two weeks ago. "Best of luck," the note read. "Now I'm headed underground until this blows over." It was from Steve Shartzer. He was still coming to terms with the past.

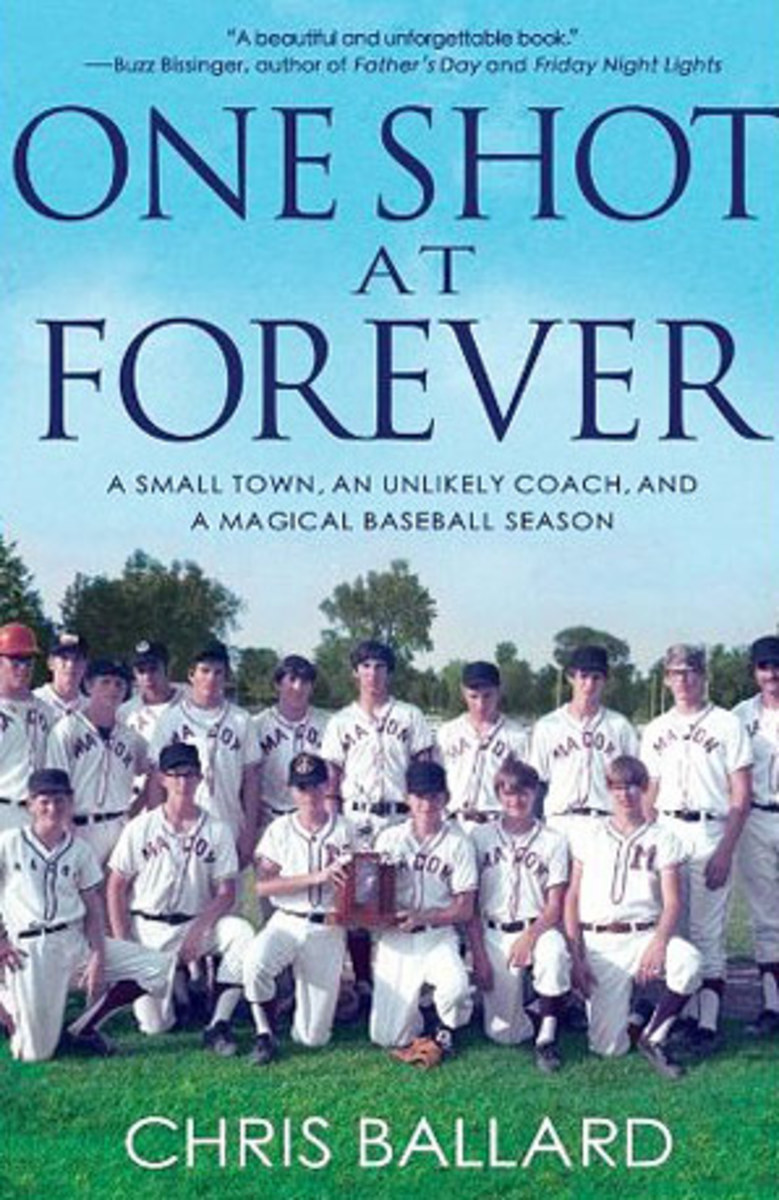

I first heard about Shartzer's old team, the Ironmen, two and a half years ago. A man named Chris Collins emailed me describing how in 1971, at a time when there were no class divisions in Illinois high school baseball, tiny Macon High made an improbable run to become the smallest school in Illinois history to play in the state finals. An undersized, undermanned squad from a town of barely a thousand, the Ironmen faced powerhouses like Lane Tech, a 5,000-student, all-boys school from Chicago. Making the story even more intriguing, the team was led by an English teacher-turned-coach named Lynn Sweet, whose unconventional methods and progressive beliefs clashed with the culture of a town still stuck in the Eisenhower era. There were obvious echoes of Hoosiers.

I flew out to Macon to investigate. The result was The Magical Season of the Macon Ironmen, which ran in the June 28, 2010 issue of Sports Illustrated. The response to the story was powerful -- in these boys and their coach, readers recognized themselves, as well as a bygone time when towns and teams were intertwined. Convinced there was a book in it, I set to work. It was then that I ran into an interesting phenomenon. It involved memories.

When it comes to sports, memory can be a peculiar thing. We can recall the tiniest details of a basketball game played when we were 16 -- a shot missed, a traveling call, a rebound bungled -- yet vast tracts of our life go unexamined. Sean Elliott, former All-Star forward for the San Antonio Spurs, recently told me that Tim Duncan came up to him earlier this season and said, "You know, I'm still pissed we lost that game in New York." Elliott had to think for a moment before realizing that Duncan was talking about the 1999 NBA Finals. "But we won that series 4-1," Elliott said. "Yeah," Duncan replied, "but it should have been a sweep." Elliott was amazed. Here was a guy with four titles who was still thinking about an inconsequential loss from 13 years ago.

And that's a professional athlete, someone who wins and loses for a living. It can be more complicated for regular people. Most of us only have a small window to be a hero -- only so many games, so many chances -- and it usually comes during high school, an already formative time that shapes our lives in ways large and small for years to come.

In the case of the Ironmen players, many delighted in re-living that 1971 season. Shortstop Dale Otta showed me scrapbooks bulging with clips, while catcher Dean Otta proudly mentioned that he was still recognized for being on "that team." Others had largely forgotten about those years, and were left with only vague but pleasant memories. Still others held onto old grudges, newly awakened by my questions half a lifetime later.

And then there was Shartzer, a star pitcher so talented that he was later drafted by the Cardinals. At first he remained so affected by that season -- feeling that he'd let people down during the playoffs -- that he didn't want to be interviewed for the SI article. When it came time for the book, it took months for him to work up the will to do it again. Finally, I flew out to see him and we sat in a Waffle House near his home in Foley, Ala. Over coffee, he told me the deal: we could talk as long as I wanted, but we were only going to do it once. He'd re-live the story -- one more time, for one more day -- but it was too painful to delve into after that. We ended up spending six hours in that Waffle house, during which time he laughed some and cried more. And while Shartzer was gracious enough to speak to me again after that, it didn't get much easier for him. "I don't know what it is," he told me at one point. "I need to get past this and I just can't."

Now, as the book -- titled One Shot at Forever -- is released, Shartzer and his teammates face one final recalibration. For 40 years the Ironmen have held on to their recollections of that season, each player's version slightly different from the next, colored by time and perspective. Now their story is out there, released from the collective memory of a few into the world. Most of the them are excited, Otta so much so that he used a screengrab of the book cover to make T-shirts and hats. Others have written heartfelt notes. As for Shartzer, his feelings about Macon, and that season, changed in important ways during the two years that I worked on the book, and by the end he'd made a return trip to see his old coach and teammates. judging by his recent note, he's still not ready to let go of his feelings entirely.

Some might find this peculiar, but I'm not so sure. After all, I'm 38 and I still dream about basketball games I lost in high school (though never, strangely enough, about the ones I won). Likewise, when I get together with certain friends over beers, I know the conversation will eventually lead us back to some field or gym on some fateful afternoon. The stories never change, of course, but we still tell them year after year. We do so to keep them alive, but also to remind ourselves that they once mattered. That they still do in some small way.

This is the way it has always gone, and always will. In two weeks thousands of teenage boys across the country will jam on their gloves, pull up their stirrups and sprint onto the field for their state's high school baseball playoffs. Chances are they won't be thinking of what could have been, or what is to come. Instead they will live in the present, even as, moment by moment, they create their past.