NCAA rules exam illustrates need to reboot rulebook; trust me, I took it

STARKVILLE, Miss. -- When Mississippi State men's basketball coach Rick Ray turned in his paper and walked out of the room after less than 10 minutes, I knew I would be the dunce for this particular standardized test.

"How'd you do?" Ray asked.

I stared at the ground. "I'm still on question No. 5," I said.

The task seemed simple enough. Take the NCAA's 30-question, open-book rules exam alongside Mississippi State's coaches Wednesday to see if I could score high enough to qualify to recruit off campus. Twenty-four correct answers allow a coach to hit the road, and coaches in every sport must pass the test once a year to keep recruiting. Other coaches had offered sage wisdom, and before Mississippi State compliance guru Bracky Brett handed me a test that induced several ugly pre-calculus flashbacks, passing seemed a cinch.

"If you can read," Arizona football coach Rich Rodriguez once told me, "you can pass."

A few days earlier, I bumped into Ohio University receivers coach Dwayne Dixon at a high school spring game in Florida. (The ensuing exchange, by the way, would have violated the NCAA's "bump rule" had I been a high school student. Dixon knew that rule because he has passed the test time and again.) I told Dixon I planned to take the test and asked for advice. He laughed. "Open the book," he said.

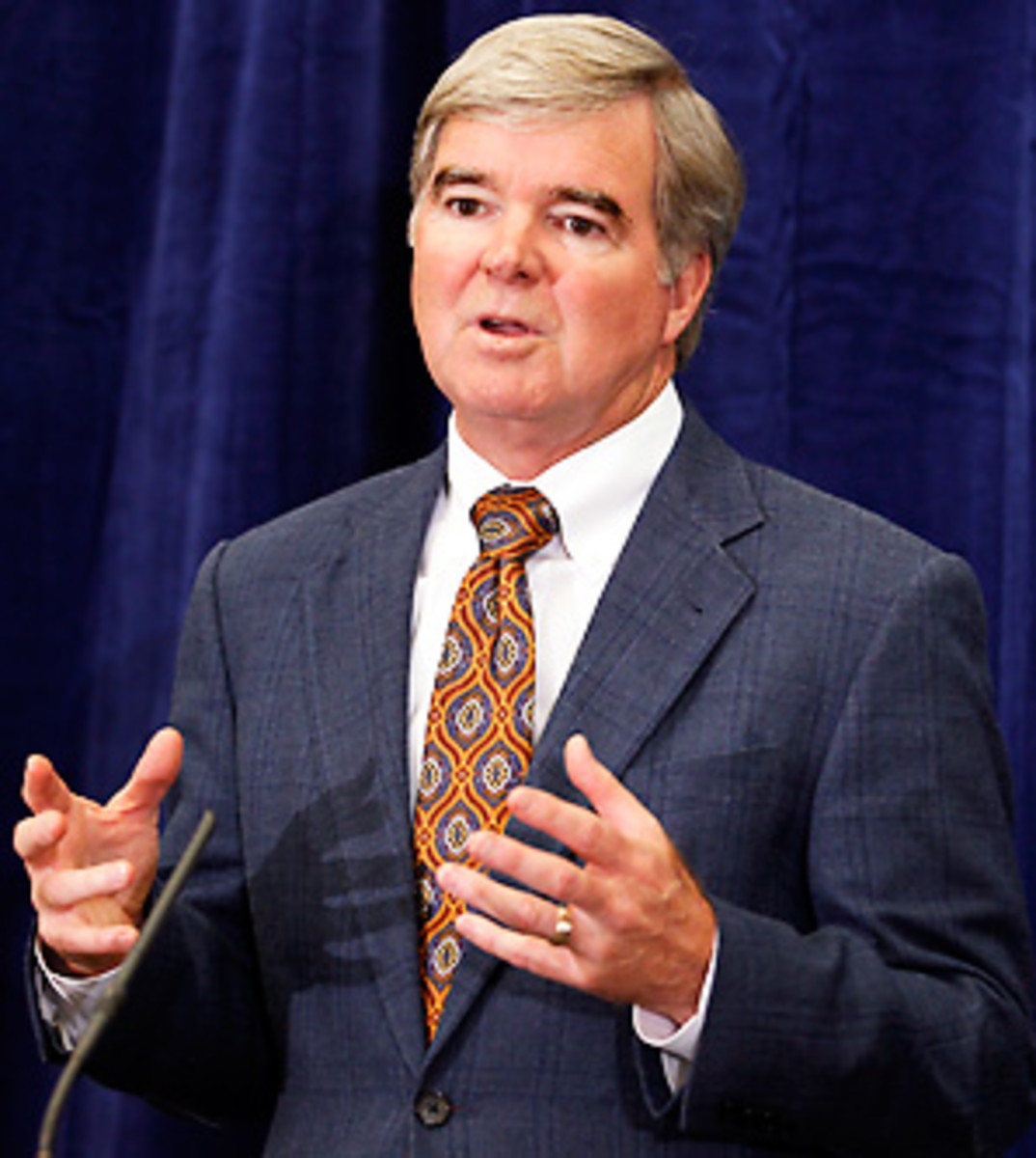

Ah, yes. The book. That would be the NCAA Division I Manual. "Be careful with the book," Mississippi State volleyball coach Jenny Hazelwood advised. "Sometimes, you'll look something up and get more confused." The 2011-12 edition of the manual is a 426-page bundle of good intentions, contradictions and wonkery that has so frustrated coaches and administrators that NCAA president Mark Emmert has ordered the creation of working groups made up of college athletics leaders to find a way to slim the volume into a more manageable tome that embraces common sense and doesn't sweat the small stuff. Alas, no one involved in the process is ready to adopt the drastically rewritten rulebook I offered last year. Still, a streamlined rulebook might help everyone involved.

Gil Grimes, the SEC assistant commissioner who came to Starkville to administer the test to Bulldogs coaches, said schools may vote to trim the rulebook within the next year. "One of the things that's being talked about is doing away with this test," Grimes told the coaches during a helpful session in which he explained and helped interpret new pieces of NCAA legislation. "So for bragging rights, you may want to pump it up a notch. This may be the last one you take."

The test -- and the manual coaches use to find the correct answers -- offers the strongest proof of the need to reboot the rulebook. Coaches, compliance officials and the NCAA enforcement staff must worry about so much nonsense that the important rules sometimes get lost.

For instance, did you know that a football coach may not have in-person, on- and off-campus contact with a prospect who was certified as an academic non-qualifier and is in his first year at a junior college? Neither did I -- until I guessed the correct answer to question No. 6 after 10 frustrating minutes rooting through the manual. Why does it matter whether a football coach speaks to an 18- or 19-year-old high school graduate during one of the brief contact periods? Short answer: It doesn't. So there you go, NCAA working groups. I've already trimmed one rule for you.

While that may sound like a minor deal, violations of such rules cause major waves. Big Ten coaches seethed when Ohio State's Urban Meyer violated the bump rule by wishing a recruit "good luck" before a game in December. After the spring 2007 evaluation period, coaches lined up to turn in Alabama's Nick Saban for violations of the bump rule. What did the schools do in response to Saban? Did they repeal a silly rule that made it illegal for famous football coaches to engage in conversations with high school students while at a school? No. They banned head coaches from visiting schools in the spring.

The intent of such rules is pure enough. If a coach is allowed to engage a prospect during an evaluation period, every interested coach will take advantage of the opportunity. All those suitors could cause an unnecessary distraction for a high school student, but guess what? When a high school player sees assistant coaches from Georgia, LSU and Miami standing on the practice field, he's already pretty distracted. Ticky-tack rules don't really make life any easier for that high-schooler. They simply give coaches another reason to turn in one another to their conferences or to the NCAA, and they give compliance directors a reason to buy Advil in bulk.

The NCAA has a bank of questions for these sport-specific compliance tests (I took a football test), and each request for a test spits out 30 randomly selected questions. Two of my questions involved the distance schools are allowed to travel to entertain prospects on official visits (30 miles). This rule, one of several revised by a recruiting working group empanelled after Miami high-schooler Willie Williams tried to eat every lobster in Florida during an epic run of official visits that Williams chronicled in The Miami Herald, might not make the cut in the new rulebook.

Three of my questions involved the composition and delivery method of recruiting materials. I missed a question about whether schools can provide a media guide to a prospect on a flash drive instead of in printed form. I answered that schools are allowed, because this seemed like the sort of tree-saving activity encouraged on most campuses these days. I was wrong. Apparently, some schools got so upset that other schools produced fancier flash drives that they made a rule forbidding anyone from recruiting via USB port.

Here is the full text of another question:

It is permissible to send a prospective student-athlete an institutional postcard that contains an athletics logo on one side and handwritten information on the opposite side.

A. TrueB. False

Thinking back to Dixon's advice, I opened the book. There, I found Bylaw 13.1.1(j).

Postcards. An institution may send an institutional postcard, provided its dimensions do not exceed 4 1/4 by 6 inches, it includes only the institution's name and logo or an athletics logo on one side when produced and it includes only handwritten information, (e.g., words, illustrations) on the opposite side when provided to the recipients. Blank postcards issued by the U.S. postal service also may be sent.

Think about that for a moment. Multiple college-educated people spent paid hours deciding the maximum size of a recruiting postcard. Remember, that rule is subsection J, which means there also are subsections A (general correspondence) through I (institutional note cards). Why did intelligent people with important jobs spend so much time on this? Partly because Oregon once produced some sweet, custom, recruit-specific comic books and some coaches, mad because they didn't think to produce sweet, custom, recruit-specific comic books, asked the NCAA to ban any recruiting materials that might tax the imagination and/or drain the wallet.

But there is good news. "I think that one," the SEC's Grimes said of the postcard rule, "is probably ripe for deregulation."

Most of these rules exist because of a desire for competitive equity. But common sense dictates that restricting the size and creativity of mailings isn't going to fool a prospect into thinking that Louisiana-Lafayette bears any similarity to LSU. That's why many of the recruiting material rules also may get chopped.

Another question involved text messages. In most sports, a coach can't text a prospect until after that prospect signs a National Letter of Intent with the coach's school. Schools created this rule in 2007 because the volume of texts from coaches had run up the cell phone bills of recruits across the country. In the five years since the rule was passed, smart phones and social media have reinvented the way young Americans communicate. A recent episode of NBC's Community summed it up best when a college-aged character poked fun at an older character by saying -- with mock horror -- that "she still uses a phone as a phone." Now, most high-schoolers have phone plans that include unlimited texting. Most don't answer voice calls, so the restrictions on those are obsolete. Texting is the American teen's preferred method of communication, yet coaches aren't allowed to use it. This could change, too. Men's basketball coaches have recently received the right to text prospects on a trial basis. Shockingly, Earth has not spun off its axis.

A few questions involved legitimate issues. One asked me to identify the characteristics of a representative of a school's athletic interests -- better known as a booster. Instead of the 30-mile rule, this is an issue that deserved two or more questions. Coaches need to be able to identify boosters so they can shoo them away from prospects and avoid NCAA scrutiny that could -- at the very least -- jeopardize the player's eligibility to go to that school. Two other questions involved recruiting services, which have been used in recent years as a way to skirt rules against paying people associated with recruits. One question asked me to identify the characteristics of a legitimate recruiting service. (Beginning next month, the NCAA will make this task easier by certifying legitimate services.) Another question asked what kind of relationship a football coach may have with a recruiting service. The answer? Not much of one. He can grant an interview to a service -- provided he doesn't break any of the NCAA's (necessary) rules that forbid coaches from publicizing unsigned recruits.

Meanwhile, men's basketball tests now include questions about what the NCAA calls an Individual Associated With a Prospect (IAWP). This is a catch-all term to describe any third party involved in a player's recruitment. This person could be an AAU coach, a distant relative, a family friend or simply a handler. Expect this term to seep into football, because much of the fracturing of the NCAA's more serious rules involves people who don't fit the NCAA's definition of a booster. By giving IAWPs their own category, the NCAA can attempt to regulate them. This may not work, but it's far less clunky than trying to slap a booster label on a handler.

With no IAWP rules to interpret, I had little trouble with the questions about the NCAA's cardinal sins. The questions about the venial sins caused more problems. The book saved my bacon on three questions, but it tripped me up on two others. The first was the flash drive question, because I misread a rule about schools being allowed to send enrollment materials via flash drive. The other question I missed involved a football-only rule that requires coaches who watch a high school game during a contact period to log an evaluation and a contact for every player on the field. I missed the football exception. For example, Bulldogs volleyball coach Hazelwood would have to log an evaluation for every player on every court she watches at a tournament, but she would not have to log contacts.

I wound up answering 28 of the 30 questions correctly. This tied me with basketball coach Ray and football coach Dan Mullen, who needed only of a fifth of the time I used to achieve the same score. "Trick questions," Mullen said of the two he missed.

After Grimes graded my test, compliance director Brett laughed when I complained that the confusing book had caused me to miss questions on an open-book test. "Now," he said, "you're talking like a dang coach."

Those dang coaches have a point.