Artist Leroy Neiman chose to see sport as a razzle-dazzle of glory

Framed in my library is a sketch that Leroy Neiman dashed off of me on the back of a menu when he was watching me speak several years ago. Leroy, who died on June 20, was somewhat better known for another sketch, the so-called "nymphette" that has appeared in Playboy since 1955 -- but of course, he's ever famous for simply being our most celebrated sports artist.

This is hardly to say he was acclaimed. Rather, he was dismissed as a garish showoff, who was all about colors and celebrity -- more of a Peter Max, without any of the grace or subtlety of Norman Rockwell, who he was often popularly compared to. Unschooled sports fans paid well for Neiman canvasses, though, and Leroy appeared unbothered by the unrelenting criticism.

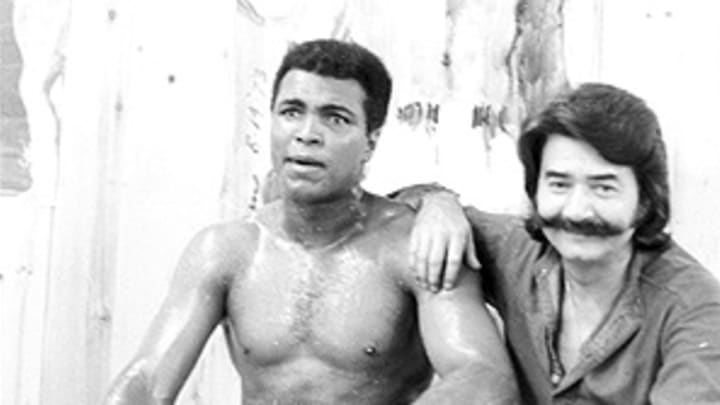

Part of the professional disdain was no doubt manifested by envy -- his television ubiquity and his illustrious physical recognition -- highlighted by that great, sweeping nineteenth-century mustache. One bitter cold night in Manhattan, Leroy found himself in the wrong part of town with no cabs in sight. He was, as was his winter wont, wearing his full-length mink coat, when he realized he was about to be set upon by three thugs. When he turned to face them, though, one cried out, "You're the guy who paints all the sports stars," and rather than mug him, they found him a cab.

Personally, Leroy was not at all flamboyant, but courteous, gentle and wonderfully philanthropic. Maybe it wasn't great art that he sold, but it ended up funding great art schools. His studio, just off Central Park, was a huge, aircraft hangar of a room; but it was a warm, welcoming place.

It's odd that sport, so gritty and vivid, so naturally celebrating the best of the human form, has not produced an accepted master since George Bellows' fashioned his boxing paintings a century ago. Ironically, just now, as Neiman passes on, a Bellows exhibit is showcased at the National Gallery in Washington. At the National Art Museum of Sport in Indianapolis, there are many fairly recent glorious works, but none are so well regarded as "Stag at Sharkey's," which Bellows painted back in 1909 -- lurid and dark and mean.

But Neiman's sold. Maybe we simply don't want to display sports art that shows the squalid side. After all, the iconic athletic piece remains the discus thrower, which was carved twenty-five hundred years ago. It is clean and graceful and elegant, a male Venus de Milo. So criticize Leroy Neiman for making bright beauty of sport, but it seems what we prefer.

And as the simple sketch he did of me fades, I'll prize it still -- not for its craft or its value, but for the kind, generous man who chose to see sport, above a handlebar, as a razzle-dazzle of glory.