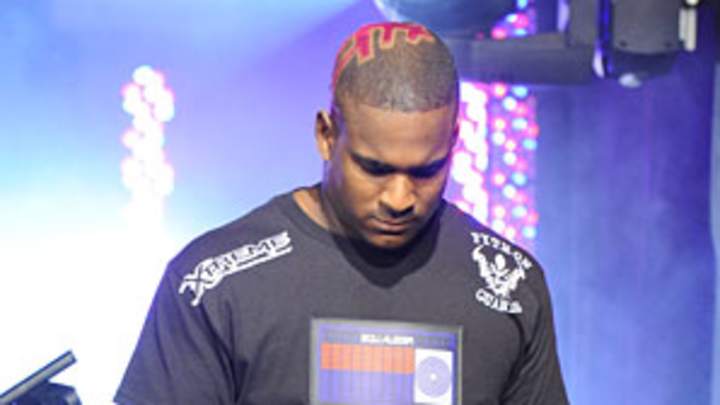

Slimmed-down Larkin set for Strikeforce middleweight debut

When Lorenz Larkin was 10 years old, he got into his first fight with a kid on the block.

He can't recall what it was over, but he'll never forget that his father had drawn the curtains to watch him from the living room window.

Fights were a common occurrence in the Southern California neighborhood where Larkin had gone to visit his father for the summer; even parents would join the circle of spectators that congregated around whichever two boys were going at it on any given day.

Larkin, a naturally athletic child, had been studying karate for three years, but this was the first time he'd put what he'd learned to work in a real-life situation. He confidently launched into his katas and advanced toward his opponent, shouting "Kaya" like he'd been taught in the dojo. However, Larkin quickly learned that the dojo and the street were two very different things.

"[Karate] didn't work at all," said Larkin. "I got my ass kicked and I started to cry."

Dejected and embarrassed, Larkin ran back into his house and was met at the door by his father, who was holding his belt in his hand.

"He told me to stop crying and whooped my ass worse than the kid outside had," said Larkin. "Then he sent me back outside."

Wiping the tears from his eyes, Larkin clinched his fists tightly and tried again to challenge his aggressor, but the results were the same. It was a humiliating lesson to learn in front of strangers, but it was even worse that his father had seen every second of it. After that day, Larkin's father would never let him practice karate again.

Larkin (12-0, 1 NC) has come a long way from that momentous day he describes as "the point where my life clicked." On Saturday, he meets former Strikeforce middleweight champion Robbie Lawler (19-8) in Portland, Ore. (11 p.m. ET, Showtime) and a win over the one-time UFC standout would mean a great deal to the 25-year-old fighter's young career. Larkin, who once fought at heavyweight, will be making his debut at middleweight.

Despite his devastating debut at age 10, Larkin always knew he was cut out for some form of professional fighting. However, his parents, who divorced when he was 2 years old, had decidedly different views from one another about combat sports.

"Dad was really protective," said Larkin, the second youngest of his father's nine children. "He was scared I'd get hurt."

Larkin's mother, whom he grew up with for most of his childhood in Riverside, Calif., wasn't as squeamish, which led to regular arguments with her ex-husband about their son's choice of pastimes.

Football was out of the question, as was any other sport that required contact.

"He let my older brother Wilbert play [football], but I was his last kid and he wanted to baby me," Larkin said.

Larkin's father, who grew up "in the hood" and today owns and runs private group homes for the schizophrenic, wanted his son to focus on his studies. Two of Larkin's older brothers had been sentenced to 30- and 60-year prison sentences for manslaughter and robbery, and though his parents weren't particularly worried that their level-headed Lorenz would follow down that path, his father wanted him to realize his full academic potential.

At age 12, and against his father's wishes, Larkin's mother enrolled him in boxing classes. She took the classes alongside him for a while, though her ex-husband wouldn't sign the permission form allowing Larkin to spar with others, let alone compete when he was old enough to.

Larkin was persistent, though. He devoted any extra time he could to the gym and continued boxing classes through high school. When he wasn't at the gym, Larkin and his friends were at the park, skateboarding and aggressive rollerblading (a trick-heavy version that has a presence in the X Games) -- the types of hobbies his father supported.

When his grades dipped during his freshman year in high school, Larkin was sent to live with his father in San Bernardino. He returned to Riverside after high school, where his friends were taking Brazilian jiu-jitsu classes, and he quietly joined them.

Larkin was now old enough to decide his own competitive fate and he entered the Desert Showdown, an amateur boxing tournament in Indio, Calif. He won the heavyweight bracket weighing 240 pounds, but his 5-foot-11 frame made him shorter than most in the division, which he knew would eventually hold him back.

Larkin realized that mixed martial arts' light heavyweight division would suit him much better and offer him more opportunity for advancement. MMA was also the closest alternative to a street fight, and Larkin had something to prove to both himself and the man who'd watched him from the window.

As there was no amateur MMA system in California in 2007, the 20-year-old Larkin moved to Kentucky, where he went undefeated in 10 bouts and whittled himself down to 213 pounds. He came back to California in 2009 to go pro.

Larkin's strong background in boxing gave him an immediate edge on the local circuit: seven of his first nine victories came from his striking, which caught the eye of Strikeforce's matchmakers. He made his debut with the promotion in April 2011, going head-to-head with seasoned K-1 kickboxer Scott Lighty. Larkin's fast hands and nimble footwork -- not to mention some flashy kickboxing he'd picked up along the way -- made him an instant crowd favorite. Larkin's second-round demolition of Lighty was considered one of the stronger debut performances last year.

In his four Strikeforce bouts, Larkin has had the distinct experience of fighting two back-to-back opponents who later tested positive for steroids. It didn't matter much with his victory over Nick Rossborough in September 2011, but his second-round defeat three months later to former Strikeforce light heavyweight champion Muhummed "King Mo" Lawal (8-1, 1 NC) was changed to a no contest by the Nevada State Athletic Commission, which kept Larkin's undefeated record intact.

Larkin, who made $17,000 for the bout, doesn't disagree that the bout against Lawal, a three-time Division I wrestling champion and 2007 world team silver medalist, might have come along too early in his career, but he also doesn't regret taking the bout when he did.

"I didn't mind testing myself," he said. "I wasn't scared to lose. Just to be considered an opponent for a fighter the caliber of Lawal was an accomplishment for me."

Larkin also doesn't dwell much on Lawal's steroid use (Lawal was suspended for nine months in March), although he thinks it might explain why Lawal felt so much stronger than him during their fight.

"I felt like a little boy with my big brother on top of me," said Larkin, who was grounded by the wrestler early and kept on his back. "I tried to explode to my feet so many times, but it just wouldn't happen. I'd never felt that before."

The Lawal fight proved a positive catalyst in Larkin's career. Not long after the bout, he switched gyms to focus more on jiu-jitsu and wrestling, the weaker parts of his game.

At Empire MMA, Larkin has spent the last five months improving his wrestling skills with Paul Herrera, a former coach to UFC Hall of Famer Tito Ortiz. Larkin has also benefited under the tutelage of longtime Brazilian jiu-jitsu instructors Romie Aram and Betiss Mansouri at Millenia MMA, another gym close by.

"I'd never implemented my jiu-jitsu with wrestling before," said Larkin, "so this a big step forward in my training."

He's also added a nutritional program for the first time to his regimen with the help of his girlfriend and striking coach Arnold DeWitt. By Saturday, Larkin will have dropped around 25 pounds for his 185-pound debut against Lawler, which should only extend the speed advantage he's likely to have over the Illinois-based power striker.

As for Larkin's father, he was one of the greatest obstacles his son had to overcome in reaching his fighting aspirations, but his father's resistance was also one of Larkin's underlying motivators.

"I wish he wouldn't have held me back. Who knows where I'd be today," said Larkin, who has his own five-year-old son named Rondell. "I think if I was a boxer, he would have accepted it faster. Seeing me on TV [for Larkin's first Strikeforce fight] changed everything for him."

Larkin said his father is a man not easy to show affection, but every once in a while, he'll catch dad bragging to his friends about his son the fighter. And each time that happens, the sting a 10-year-old boy felt as his father watched him disappointedly from the living room window becomes less and less.