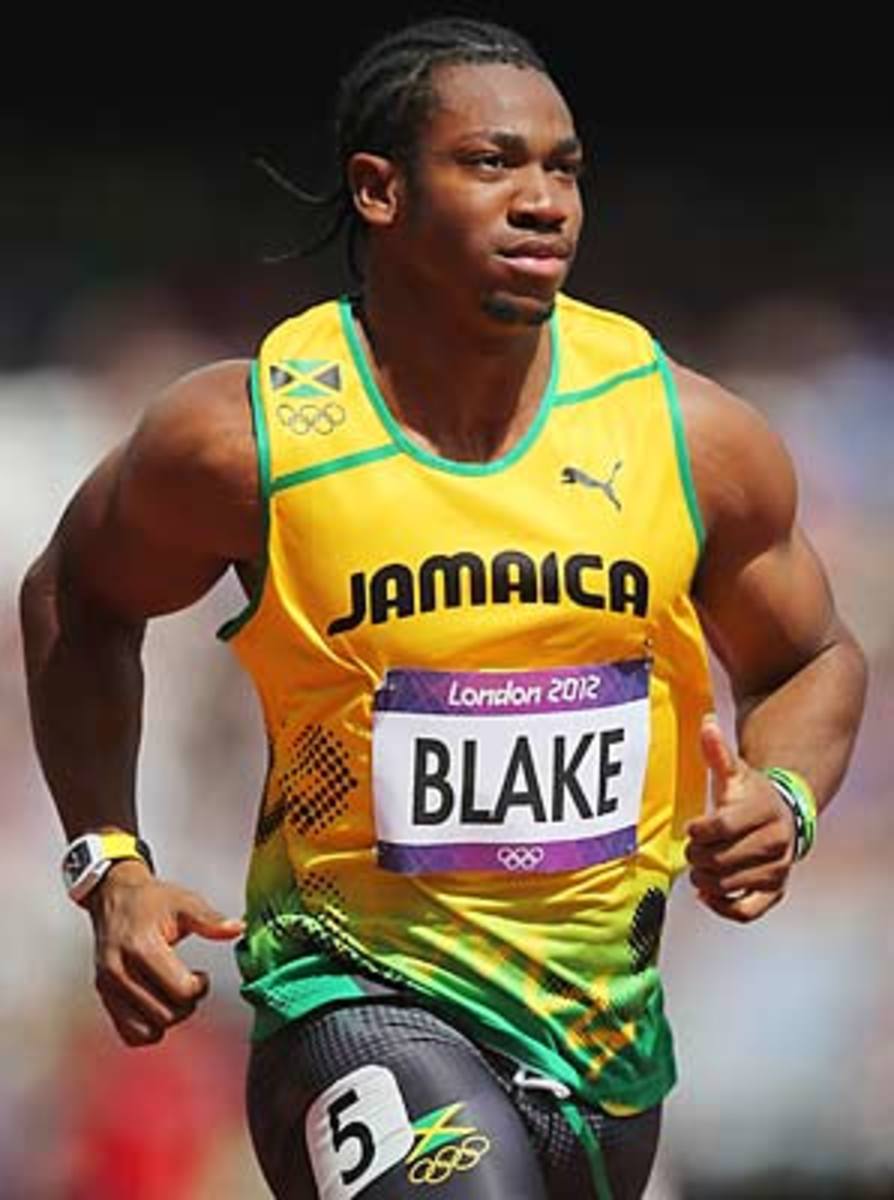

After sharing the spotlight, Blake renews rivalry with Bolt in London

LONDON -- "Da ites by great mon."

Blank stare. So Yohan Blake said it again.

"You know? Da ites by great mon reached and kept?"

Still nothing. So he slowed down.

"Da heights by great men reached and kept were not attained by sudden flight, but they, while their companions slept, were toiling upward in the night." Ladies and gentlemen, Yohan Blake, reciting his favorite Henry Wadsworth Longfellow poem to a journalist standing across from him in a hotel lobby in New York City two months ago.

It's a passage always in his mind. He sometimes uses variations of it in interviews. For example: "When you're sleeping, I'm working. I'm toiling through the night. It's what great men do."

He said the first few words of the Wadsworth into a microphone at a packed press conference on Wednesday -- "Da ites of great mon" -- but he said it so quickly and with such a strong Jamaican accent that there didn't appear to be a single person in the room who understood.

Too bad, because the world knows so little about Blake. Before that press conference, one British photographer turned to the other: "Have you ever seen Blake?" The response: "I'm not sure."

Though Blake is only 22, his work ethic is already renowned in the track world. In the famed, rural Kenyan training mecca of Iten, there is a single article about sprinting tacked up on the bulletin board outside the weight room. It's there because it includes Blake saying that "[Usain Bolt] knows I work harder, much harder ... He has said it himself." Still, Bolt has insisted he won't let his younger, smaller training partner take his Olympic title in the 200, his favorite event. (It happens to be Blake's favorite event too.)

Bolt himself has said that he's had to increase his training intensity since Blake joined him. He's the one who gave Blake his nickname, "The Beast," for his ferocious workouts. "When coach [Glen] Mills gives me a training plan," says Blake, "I damage it." Perhaps it spooked the man who wrote this in his 2010 autobiography: 9.58: Being the World's Fastest Man: "I'm so lucky that I'm raw talent," Bolt writes. "If I really worked at it I could be extremely good indeed, but I never have ... missing gym and training sometimes, and not doing all my workouts. It's hard, man. I don't know how some sportsmen do it."

Fortunately, he has a front row seat in practice. According to Blake, when Bolt stays late at practice, their coach jokes, "Big man, what you doing here?"

Where does it come from? "I come from a very humble background," Blake says. But so did Bolt. "I knew hunger and poverty. Sometimes we don't have money to go to school. Some time I have to sell bottles. Some time go to our neighbors and ask our neighbors can you help us. I didn't born wit a gold in my mouth. Ya' know I have to work for what I want and I think that what giving me this drive today. When I'm out there I say, 'Look, you have to run for your mom. You have to run for poor people.' And so I represent a lot of things when I'm out there running." He continues. "My uncle took us out of Montego Bay and moved us to Old Harbour. And from the move to Old Harbour, I said, 'Look, I'm going to be something.'" And so he started ... playing cricket. "I was really good, but I made the transition to track and field [when he was 12] and I make it to this beast."

Blake is planning a surprise for his mom which he won't disclose, but says of his parents -- his father worked in a bar and his mother was a domestic worker -- that, "they're ok now," no longer living in poverty. And yet, the drive persists, to reach the heights of great man. To surmount the great heights of one very tall man, in particular. "When other people sleeping, I'm working," Blake says, in yet another variation of his Wadsworth fugue. "Yohan is working even when he's watching TV. That's me."

So driven is Blake, that his work ethic might actually sometimes hold him back.

***

Blake's sterling times have tended to come like bolts from the blue, almost out of nowhere at the end of a season. All sprinters get faster toward the end of the season, but not like this.

Blake's fastest 200-meter time of 2011 was a 20.38 in May, all the way until he dropped a 19.26 in September. That was the second fastest time ever run to Bolt's 19.19 at the '09 world championships in Berlin, and Blake would have had the record if not for a reaction time at the start that approximated your grandmother hitting the gas pedal when the light changes. (Not to mention the fact that he ran a subpar curve, before torching the straightaway.)

Says Ato Boldon, the four-time Olympic sprint medalist and NBC track and field commentator: "Blake lifts almost, I would think, too much. When he first comes out of the weightroom he can't sprint to his maximum ... The further he is from lifting all those weights, the faster he runs."

Boldon's theory actually has a physiological basis. Muscle biopsy studies have found that sprinters seem to have a high proportion of "fast-twitch" and "super fast twitch" muscle fibers -- type IIa and type IIx fibers, in scientific terms -- the kind that contract violently for explosive movement. Lifting weights hasn't been shown to cause fast-twitch and slow-twitch (type I fibers) to interchange, but it does cause some IIx fibers to switch to IIa, which means the athlete's muscle fibers are getting slower. When the athlete stops lifting, however, there's a rebound of super fast fibers. And Danish scientists actually documented an "overshoot." For a limited time following the cessation of heavy lifting, that is, an athlete actually has more super fast twitch muscle fibers than at any other time. (Over weeks to months, the overshoot comes back to normal.) Perhaps, then, Blake timed his lifting -- and when to stop lifting -- very well at the end of last season. (The Danish scientists suggested athletes should aim for the peak of the overshoot at the most important time of their season.)

Tomorrow night, the world will see if Blake timed it right. He seems to have done everything else right. He seems to have taken the best of Bolt -- his sub-zero cool under pressure -- and left the worst, an occasionally lax work ethic. "It's not really about seriousness or being straight-faced all the time," Blake says. He previously told SI that, "Usain showed that you can relax and do funny stuff before the race and it pays off. Not thinking about pressure has been working out for me."

Blake insists he doesn't think about pressure before the race. Does he think about the perfect sprinting technique? "I don't really think about form and technique," he says. "I'm just thinking about when I go out there, I'm just going to kill people." He smirks. "Not kill, running kill, you know."

Blake is already a pro at not being drawn into barb-slinging against Bolt. At his press conference Wednesday, Blake fielded the sports equivalent of the old crime reporter trap-question, "So when did you stop beating your wife?" The sports reporter asked: "If you beat Usain Bolt, would it be because of your confidence?" Blake laughed, and said that he's "not really focused on Usain Bolt." In high school, Blake teamed with professional sprinter Nickel Ashmeade at St. Jago, so training with and befriending an on-the-track rival is nothing new.

Not to say that Blake isn't thinking about Bolt. In New York City in June, Blake, who won the 100 meters at last year's world championships after Bolt was disqualified for a false start, said that he'd like to win the 100 and the 200 at the Olympics because "people will have even more deeper respect, because ... I don't really want to get into it." But pressed, he continued. "Once people said I was in his shadow because he was the man." He corrected himself. "He is the man, I should say, of track and field, and for me to move away, making my own name I think is really good."

Like Bolt, Blake came from humble, rural beginnings. Like Bolt, Blake wanted to be a cricketer until he was spotted running at Jamaica's school "sports day" by an astute principal who turned him to track. Like Bolt, Blake became a local icon when he starred at "Champs," Jamaica's raucous, national high school track championships, which sells out National Stadium in Kingston. In '03, Bolt set the Champs record in the 200 (20.25) and the 400 (45.35). In '07, Blake set the Champs record in the 100 (10.21). Because they didn't overlap in high school racing, the Champs record book is a sort of spotlight that could easily be shared.

In London's Olympic Stadium, tomorrow, the sharing ends.