Goat vs. G.O.A.T.: The History Behind Sports's Antithetical Animal Analogy

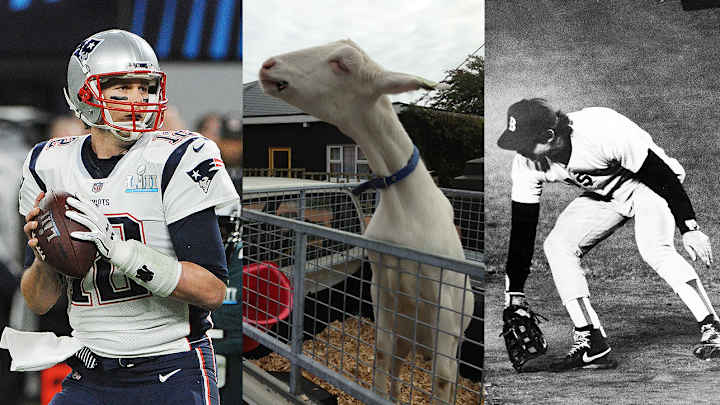

The picture accompanying this essay is of a fine Irish goat, which I took outside the main gate of the Listowel Race Course during the 155th running of the annual harvest racing festival in 2013. If I recall correctly, your man the goat was part of an advertising campaign for farming implements, of which he was said to be one. He did his job very well, as you see.

(A brief aside here. The appellation “your man” is often attached to third parties of many sorts and species. For example, “Your man the butcher has a drop taken. Please relieve him of the cleaver.” The great Irish genius Flann O’Brien made great use of it, once even referring to, “Your men, the birds.” Conclusion, as he once wrote, of the foregoing.)

Once they’d separated as a species from sheep, which experts say happened 25 million years ago, goats have a noble history dating back to (drum roll, please) the dawn of civilization. In Mesopotamia’s Fertile Crescent, the bezoar goat may well have been the first domesticated farm animal. They are prominent in almost all human mythologies. Two goats named Tanngnjóstr and Tanngrisnir—pronounced “Tanager” and “Trichnosis,” I believe—were said to pull Thor’s chariot and, every night, he would eat them and then bring them back to life with his hammer. The Greeks thought so highly of goats that they made them the lower half of the god Pan, and Greeks, Egyptians and Romans all thought highly of the goat as a primal symbol of sexytime.

The Bible is a bit harsher on the species. Celtic mythology gives us the Bocanach, a huge goat-creature that menaced travelers on dark country lanes. Goats are all over the Bible as well. In the Old Testament, they are highly praised for their utility as everything from burnt offerings to being the raw material for a tent over the tabernacle. However, in the New Testament, there’s that whole “dividing the sheep from the goats” passage from Matthew that complicates things, as it is the goats among us who are sent to everlasting perdition.

So, goats are deep in our cultural memory, no matter out of which part of the world our ancestors sprang. Somewhere in the dim past of American sportswriting, though, the goat became something different. A goat was an athlete who failed, garishly, hilariously, and at the worst possible time. In 1908, in the middle of a hot pennant race between his team and the Boston Braves, Fred Merkle of the New York Giants failed to touch second base on a walkoff single and, when he was called out, they had to replay the game a week later—and the Giants lost. This has gone down in history as Fred Merkle’s boner; which, I admit, is worse than being called a goat for all eternity, but you get the point.

The history of our sports is loud with the braying of the goat. The butt-fumble. Wide right. The own goal from Colombia. (In this case, tragically, the goat actually was sacrificed.) Roberto De Vicenzo’s scorecard. Willie Shoemaker, maybe the best jockey of all time, standing up too soon and costing Gallant Man the 1957 Kentucky Derby. Earnest Byner’s fumble. Chris Webber’s timeout. Bartman and Buckner and a thousand others on thousands of other playing fields. (Being the goat in high school can be worse than failing in front of millions of viewers. See that awful Robin Williams movie, The Best of Times, for details.) In The Natural, right before Robert Redford smites the home run that causes a massive power failure, Robert Duvall is finishing up a cartoon in which Redford’s Roy Hobbs, who’d struck out in every previous at-bat, is shown wearing the goat horns. You can look it up.

For centuries, from the Gospel of Matthew to the bleachers in Wrigley Field, nobody wanted to be the goat. Then, sometime in the last ten years, everything changed. Being the goat—or, more precisely, the G.O.A.T.—became the ultimate in athletic achievement. It confuses us old-timers when we hear it. Truly, it does.

Maybe it was Tom Brady who did it. Years ago, GQ Magazine did one of the first serious fashion photo spreads with Brady and, for reasons which passeth understanding, the photographer chose to pose Brady cradling a darling baby goat. As you might imagine, this set off general hilarity among Brady’s teammates. The quarterback showed up for a work a few days later to find the locker room festooned with copies of the picture; one of Brady’s offensive linemen even wore a copy on his back. Flash forward then to 2017, when Brady turned 40, his teammates celebrated by bringing five live goats to practice, one for each of Brady’s Super Bowl wins, because, by then, being the goat had developed an entirely new meaning.

G.O.A.T.

Greatest. Of. All. Time.

It used to be easy to identify the goat. The goat was the athlete in front of his locker with the 100-yard stare in his hand. The goat was Mike Torrez, the man who surrendered the home run to Bucky Bleeping Dent in 1978, standing in a tunnel under Shea Stadium in 1986, moments after Bill Buckner’s error, and hollering, “I’m off the hook!” Well, no, pal, you weren’t, but I take your point.

Now, though, people argue about who is the G.O.A.T. Is Brady truly the G.O.A.T.? According to the fans in Foxborough, and an informal count of livestock wandering the facilities there, he is. There is an ongoing battle now between partisans of LeBron James and Michael Jordan as to the relative G.O.A.T.-ness of them both. Tiger Woods was the G.O.A.T until injuries and the carnival life removed the punctuation marks from the word on his behalf. It is only three small periods between G.O.A.T and goat. An ellipses that eclipses.

Trump Has Made the NFL His Punching Bag. The League’s Best Response Is Defiance

Anyway, I find it hard to see why anybody would want to go down in history as the G.O.A.T. It still sounds to the naked ear as considerably uncomplimentary, particularly when yelled at top volume on the sports-talk radio programs. (To be fair, so would Ode To A Nightingale.) The late comedian Victor Borge used to do a bit in which he would “pronounce” punctuation marks. The period was pronounced as a very indelicate homonym for certain bodily functions. Nevertheless, if you want to use G.O.A.T in casual conversation, it would seem incumbent on you to use the Borge method so as not to confuse the rest of us, and those period sound effects could cause you embarrassment at formal dinner parties. Also, if you don’t use the sound effects, and you refer to Tom Brady as the G.O.A.T., how are people to know whether you’re talking about his whole career, or that unfortunate fumble at the end of the Super Bowl last February? You can see the problem here.

Moreover, and to get deeper into the etymological weeds, never to return, how do we measure the greatest goat of all time—the G.O.A.T. of all goats. Is it Buckner? Bartman? De Vicenzo? Or do we go all the way back to poor Fred Merkle, who certainly was the G.O.A.T. of all goats of his time? Is Fred the G.O.A.T., or is he the goat, or is he both? And who can say? Maybe we have to go all the way back through the mists of time to find the source of this confusion, to find when goats became G.O.A.T.’s and confused the issue all to hell. Maybe we have to go back to our pagan origins, as played out in the darkling, haunted woodlands of the state of Maine.

In 2016, shortly before Christmas—or Yule, if you want to be pagan about it, a man named Phelan Moonsong went to court and won the right to wear his goat horns while having his picture taken for his driver’s license. Mr. Moonsong is an ordained pagan priest. This was a tremendous win for religious freedom, and for driver’s license photos, as should be obvious. Still, it was shortly after Mr. Moonsong’s big win that I first heard goat used as G.O.A.T. in reference to Tom Brady. I sense the presence of invisible forces at work, and I hear the grinding wheels of Thor’s chariot behind the whole business. Coincidence? I think not.