Scouting Buddy Hield, the NBA draft’s best shooter

Your teams. Your favorite writers. Wherever you want them. Personalize SI with our new App. Install on iOS or Android.

With the NBA draft fast approaching, SI’s Scouting Department is offering a rare look at its intel on an elite prospect.

Subject: Buddy Hield, 6'4" senior shooting guard, Oklahoma

Projected draft range: First round, picks 3–7

2015–16 stats:25.0 ppg, 5.7 rpg, 2.0 apg (50.1% on 2s, 45.7% on 3s, 88.0% on FTs)

What is a Buddy Hield?

He’s the best shooter in this draft—and its best bet to stick as a starting two-guard in the NBA. During the 2015–16 season, Hield was the best volume scorer in college basketball and the most captivating player of the first two weeks of the NCAA tournament. His Sooners started a three-guard lineup; two of them were definable as combos (Isaiah Cousins and Jordan Woodard) while Hield operated in always-looking-to-score mode. Nearly 23% of his possessions came in transition, as he would leak out after opponents’ misses and run the wings for an Oklahoma team that had the fastest tempo in the Big 12.

Hield typically began his halfcourt possessions in one of the corners, and then (with almost equal frequency) either ran off screens to for catch-and-shoots, handled the ball in wing pick-and-rolls, or isolated to set up off-dribble pull-ups. As defenses increasingly hounded him—”Everyone plays me tight right now,” he said at the Final Four—he found space to shoot by extending his three-point range to NBA distance, without sacrificing much accuracy. Hield is a perpetually cheery Bahamian, from Eight Mile Rock, outside of Freeport, and he enjoys late-night shooting workouts set to dancehall-reggae SoundCloud mixes that are played at the same decibel level that’s produced by a jackhammer.

Intel from the early stages of Hield’s relationship with the three

As a young teen in the Bahamas, Hield shot the ball from hip level, and a made three was often cause for celebration beyond what is typical in stateside hoops. Every time Hield hit a trey during a game that his older brother and biggest fan, Chavez, attended, Chavez would respond by doing a crazy, sprinting lap around the perimeter of the court. Buddy very much enjoyed this; certain Bahamian authorities, not so much. “Back when Buddy was 15, he played in a tournament [in Freeport] called the Vitamalt,” says the boys’ mother, Jackie Swann. “And my daughter called me from it and said, ‘The police got Chavez.’ I said why? She said, ‘He ran around the court again after Buddy made a three, and they threw him out.’”

Intel regarding Hield’s advanced “feel”

This happened during one of the Sooners’ 2015–16 preseason practices, when they were breaking in a new batch of basketballs. Byron Peak, Oklahoma’s senior student manager, watched Hield stop a shooting drill and examine a ball with some annoyance. “And then,” as Peak recalls, “Buddy pulls an [air-inflation] needle out of his sock, sticks it in the ball, lets out some air, puts the needle back in his sock and starts shooting again. All of [the managers] were just like, ‘What was that?’”

The deal was that Hield shoots so much that he could tell the ball was inflated beyond the ideal 7.9 pounds per square inch. The managers appreciated his advanced feel, but they had to implement a NO MORE NEEDLES policy for Buddy. They would do the deflating from then on, rather than risk their star scorer (or a teammate) getting hurt in some freak, sock-needle stabbing incident.

Observations from the Sooners’ practice gym

I observed three practices this season in the gym attached to the Lloyd Noble Center—one in January and two in March. In each case, Hield’s allergy to downtime was evident. He seems to need a ball in his hands at all times, and during every break, no matter how brief, he finds a way to attempt a shot. Hield’s group of four is waiting its turn to run a full-court drill, and the action is at the other end? He’s putting up a shot. The team breaks its center-court huddle and heads toward drill stations? He’s putting up a shot. Everyone’s turning their practice jerseys to the crimson or white side out after being assigned scrimmage teams? He’s changing his jersey quickly enough so he has time to take a few shots before the action resumes.

Such behavior makes sense if you’ve seen that hoop from his grandparents’ yard in the Bahamas—the one with the milk crate, its bottom cut out, nailed to a long plank of scavenged wood. The young Hield had such a yearning to put up shots that he constructed his own goals, driving his grandparents nuts in the process (says Swann: “My mother used to say, ‘I want to kill this boy, because he’s always bringing trash in my yard.’”). When Hield is in a modern practice gym, surrounded by six perfect hoops, he cannot resist taking advantage of them.

• LeBron steps up & Warriors unravel in Game 6

Hield also cannot pry himself away from said gym. I already mentioned his near-nightly habit of solo shooting workouts, but he also had a more structured, morning shooting routine that he’d do with then-Sooners assistant Steve Henson—and this, too, was in addition to Oklahoma’s regular practices. Over the course of four seasons, Hield improved so much that the Sooners had to alter their drills to keep pace. “We had to change some of our shooting games that we’ve been doing for 20 years, because they’re too easy for him now,” Henson said in January. “We used to have guys try to make three treys in a row, from five different spots, in 90 seconds. But Buddy is to the point where he always makes [three in a row from] seven spots, and sometimes doubles back for an eighth, which is just phenomenal.”

This carried over to his in-game shooting

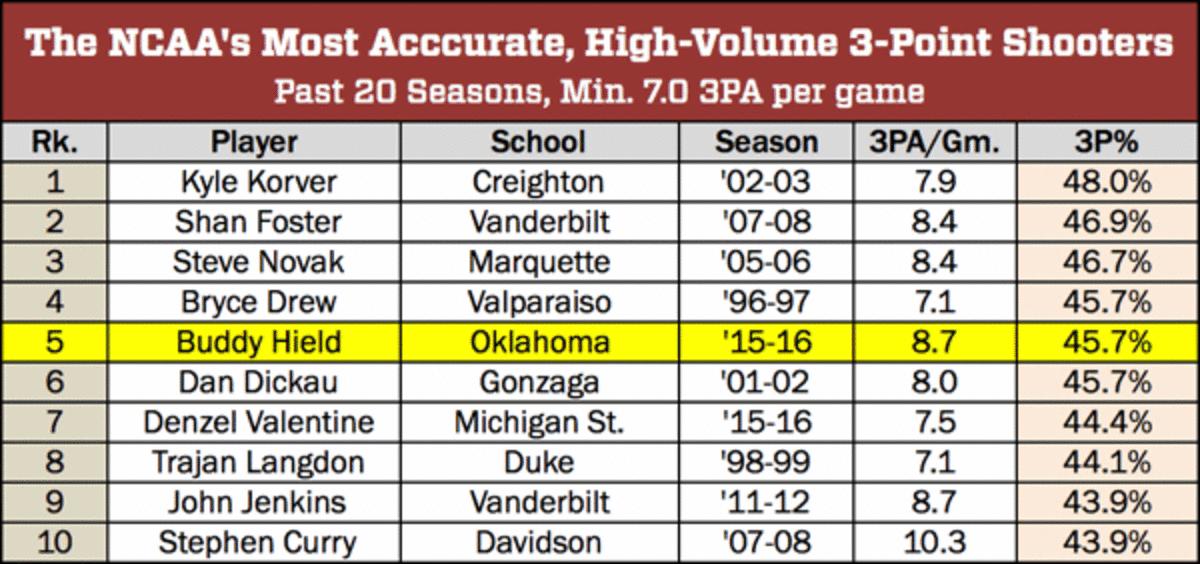

Hield’s senior-year three-point stats put him in some excellent company. Over the past 20 college seasons, these are the 10 most accurate long-range shooters who have attempted at least 7.0 threes per game:

He was a stratospheric off-the-catch shooter in 2015–16

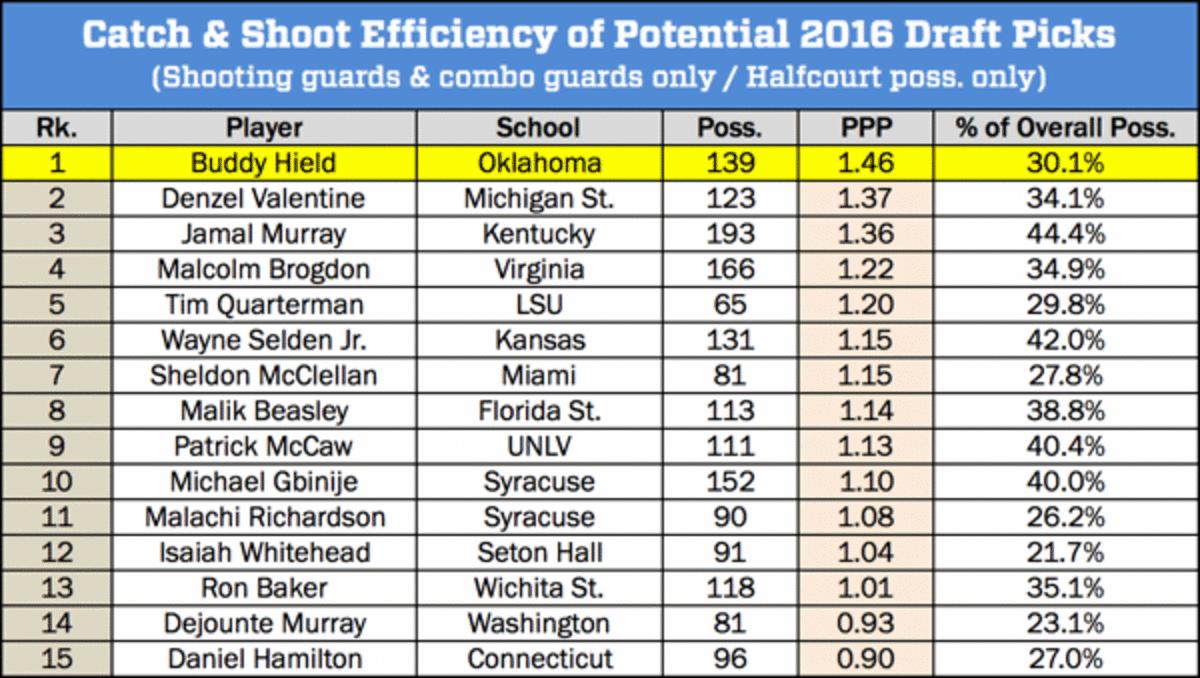

Hield scored 1.46 points per possession in halfcourt catch-and-shoot situations. Among shooting guards that are candidates to be drafted in 2016, Hield was in a catch-and-shoot efficiency tier all by himself; tier B consisted of Michigan State’s Denzel Valentine and Kentucky’s Jamal Murray; and everyone else was in tier C:

Chart data source: Synergy Sports Technology

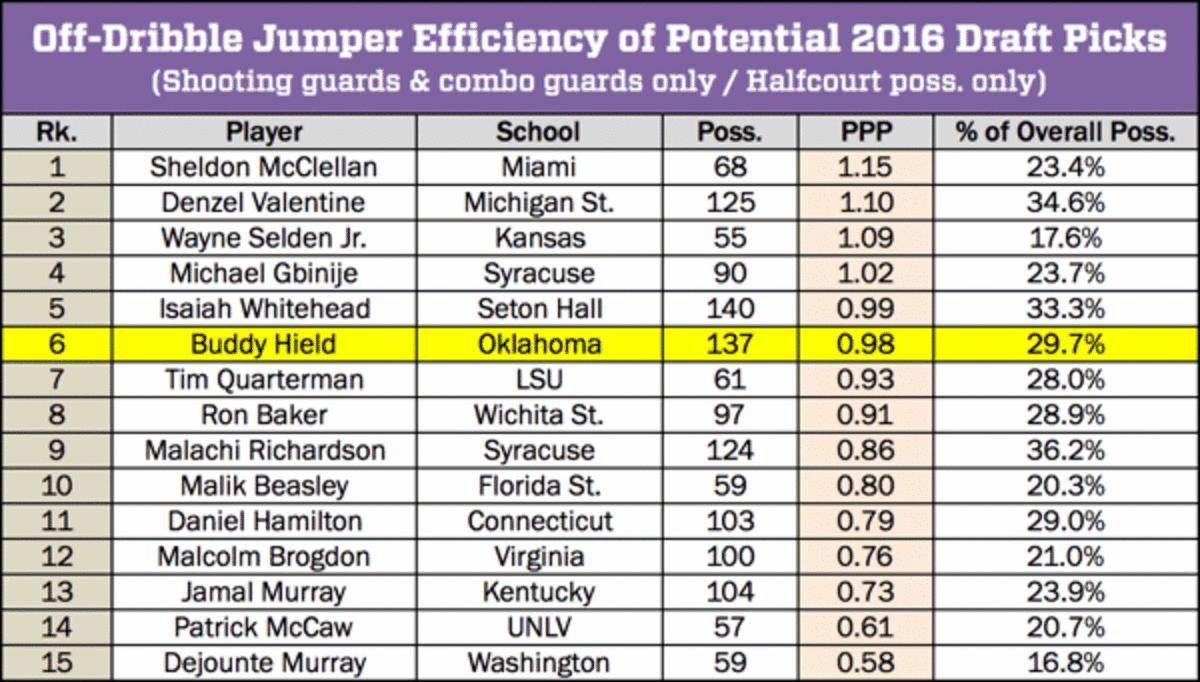

As an off-dribble shooter, Hield was human

In part because Hield attempted plenty of high-difficulty, off-dribble shots, he did not blow away the field in off-dribble efficiency, ranking in the middle of the pack among 2016 shooting-guard prospects. However, his 0.98 PPP was significantly better than the 0.73 PPP posted by his main competition to be the first two-guard drafted, Kentucky’s Jamal Murray.

Chart data source: Synergy Sports Technology

Reasons for reservations

The playmaking aspect of Hield’s game is limited. He averaged just one assist per 10 possessions used this season, and had an assist-turnover ratio of 0.66-to-1—but Oklahoma wanted him to have that score-first-second-third-and-fourth mentality. I’m curious how he’ll adapt to an NBA role as a non-go-to guy, and whether he can attack from the wings and create shots for teammates.

What dampens Hield’s NBA projections, in the eyes of advanced statistical models, is how long it took him to become a star. The later in a college career that that happens, the less likely a guy is to thrive in the NBA—and Hield was a 22-year-old senior when he made the leap from solid, Big 12 scorer to Naismith-and-Wooden winner. His three-point percentages, in order from freshman to senior year, were 23.8, 38.6, 35.9 and 45.7. He didn’t become an elite off-the-dribble scoring threat until 2015–16—after NBA teams told him, following his junior season, that he wasn’t a good enough ballhandler or shot-creator. “It kind of embarrassed me, because I’m always in the gym,” Hield said in March. “You just gotta be a man, and you either fix it or you don’t fix it. I’m happy I fixed it.”

There are, however, reasons to regard Hield as a different (and more attractive) kind of late bloomer: He didn’t get much skill development in the Bahamas prior to his arrival in the U.S. in 2010, and his shot underwent a complete makeover at Oklahoma—from a long, low motion with weird elbow position and a release point on the wrong side of his face, to the picture-perfect, repeatable form he has now. He was excellent once his mechanics caught up with his work ethic.

• The beautiful chaos of the NBA Finals

What fuels him, nutritionally

Hield is a sugar fiend. His fuel during breaks in his January shooting workouts was handfuls of Haribo gummy bears and swigs of Monster Energy drink. In March, when the Sooners were playing in Oklahoma City for the opening rounds of the NCAA tournament, he put out an urgent Twitter call for a “care package”—of Red Bull, Haribo and Snickers—to be delivered to the team hotel to give him an energy boost.

Blue Raspberry-flavored Jolly Ranchers were also essential to Hield’s success. Cody Johnson, another Oklahoma student manager, says, “During practice, Buddy liked to pick out the all blue Jolly Ranchers”—from the candy cup on the scorer’s table—“and put them in his socks. Then he started opening games with a blue Jolly Rancher in his mouth, playing maybe the first five minutes with it in, and then you’d see him just spit it into his hand and chuck it in whatever direction, sometimes right into our bench.”

What fuels him, motivationally

In the Bahamas, the notion of having his own bedroom—or even his family having its own house—was as foreign to Hield as having a modern practice facility. Swann and her children occupied one room of her parents’ house. “There were seven kids, and my mom made eight,” says B.J. Simmons, Hield’s oldest brother, who ran track at Central Arkansas. “Most of us were sleeping on the floor; there was a rug, and Buddy slept on that with a blanket over him. It didn’t bother us; it just made us able to adapt to any situation.”

For the latter half of this season, Simmons, another brother, Kervin, and Swann all lived with Hield (and teammate Isaiah Cousins) in his campus apartment, alternating between the bed, an airbed, the couch and the floor. There were many nights in which Hield—as a college senior—shared his bed with his mother. “He wanted us there,” Simmons says. “Him looking at us is key to him not forgetting where he came from, to not getting satisfied. He feels like, ‘I’ve got a family to feed, so I can’t slack at all.’ A lot of people at home said we weren’t going to amount to anything, and we beat the odds.

“A big island thing is that everybody likes to bet on stuff. Everybody always wants to get over on something. Buddy liked to bet, too. But the only thing he’d bet on was himself—that he was gonna win.”