The Dialogue Moves Forward

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. — Of all the people who had an opinion about Richard Sherman following his famous on-field interview after the NFC Championship Game, here was one name the Seahawks cornerback hadn’t heard before: Bill Clinton.

The 42nd U.S. President sat in a box for the Seahawks’ Super Bowl XLVIII win along with Domonique Foxworth, the president of the NFL Players Association at the time. Foxworth finally relayed what he heard to Sherman yesterday, during a panel discussion at Harvard Business School—that seemed as good a time as any.

“President Clinton was saying how he believed you were misunderstood, and you were one of his favorite players,” Foxworth told Sherman. “I just wanted to share that with you, because it’s important. He’s a thought leader, and he didn’t have to say that—we were just watching the game.”

That’s a big part of why Sherman was at Harvard yesterday as a “visiting professor,” along with Cardinals receiver Larry Fitzgerald and Texans running back Arian Foster. Foxworth, now a first-year MBA student at Harvard, invited the three players to speak on campus because of the way they move the needle off the field.

Fitzgerald has taken on philanthropic causes in the U.S. and worldwide. Foster visited Occupy Wall Street and has made a persistent call for NCAA players to be compensated for their labor. But it was mainly Sherman who inspired Foxworth to ask his former NFL colleagues to headline two standing-room only panel discussions, one at Harvard Business School and the other with Harvard undergraduates—not because of what Sherman said in that interview with Erin Andrews, but rather how he handled the public reaction. Sherman, starting with his column for The MMQB, changed the discussion by asking critics of his charged interview why he, an African-American from Compton, Calif., with a Stanford degree, had been labeled a “thug.”

The players and Foxworth had some testy exchanges with the students. (Jenny Vrentas/The MMQB)

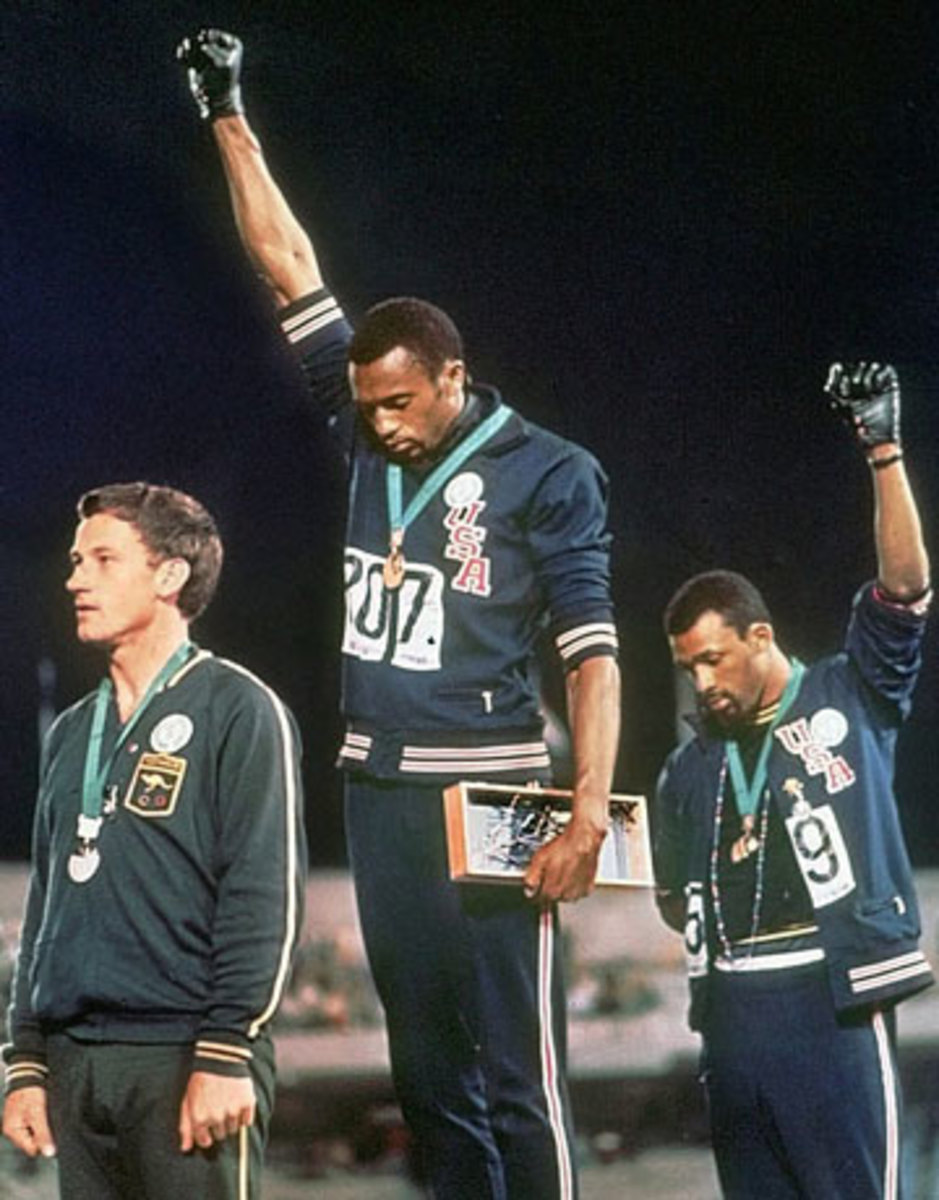

“He took that opportunity to force us to have a real conversation, which I think is incredibly commendable and is part of today’s modern athlete,” Foxworth said. “I think a lot of what our athletes are today is more like the athletes of the ’60s and the ’70s, the black athletes of that age, especially John Carlos and Tommie Smith. They worked their entire life to win that sprint, and on the medal stand, rather than basking in the glory of their achievement, they put up the fist and let everyone know there was a problem.”

The comparison to the political statement made by the two American sprinters at the 1968 Summer Olympics is a strong one. But Foxworth made that link, because as both traditional media and social media today have made athletes more accessible, he sees a group of players using that platform to advance social causes mattering to them—whether it be gay rights, charitable aid or race relations.

“It is something I consciously think about,” Sherman said on his way off the Harvard campus. “The bias, the racial discrimination, the classism has continued, so when this discussion is happening, it’s still relevant today. The change is still happening.”

When one student asked how the depiction of black athletes can be changed, Foster fired back, “You’ve got to tell me what the depiction is right now — it’s your depiction.”

Because of the interview heard around the U.S., Sherman was in front of hundreds of Harvard students, continuing the discussion he fueled. Each panel was intended to have a different focus—“Social Capital of the Savvy Athlete” in the first, and “Race and Justice in Big Time Sports” in the second—but both sessions kept coming back to race.

Today’s athletes still grapple with issues such as being called the n-word by opposing fans, as Foster said happened to him during a road game at the Patriots’ Gillette Stadium. Said Foster, “But you have black people on your team, too. I don’t know what their goal was.” He watched the aftermath of Sherman’s interview from afar, and called the way his peer handled the fallout in the foreground of the game’s biggest stage “brilliant.”

Foxworth sees today’s more active athletes carrying on the legacy of Smith and Carlos in Mexico City in ’68. (AP)

“If you call Richard Sherman a thug, you have never seen a thug. That’s not to discount [Sherman’s] street credibility,” Foster said. “To have those discussions at Super Bowl Media Day, that’s huge. I don’t really care how I’m viewed today, or how an athlete is viewed today, just as long as we get that conversation started.”

The conversation, though, is not an easy one, even for those who initiate it. In one tense moment yesterday, Sherman bristled at a Harvard undergraduate who asked if the cornerback’s creating a controversy, and then responding to it, is the most successful strategy. Later, when a Wellesley College junior asked how the depiction of black athletes can be changed, Foster fired back, “You’ve got to tell me what the depiction is right now — it’s your depiction.”

There is no neat box for the subject of race in sports, but rather an onion with many layers to peel back. But three months after finding himself at the center of a firestorm that shocked even him, Sherman—a man likely soon to become the league’s highest-paid cornerback—sees a relatively tidy moral to that story.

“The lashing we’ve taken isn’t that crazy,” Sherman said. “You see us still walking, talking, moving, grooving. I think the fear of the backlash and the media perception and the judgment and the criticism is starting to get tempered. How much bad can you talk about a person? How much negativity can you bring a person? … The criticism eventually stops. It eventually turns around and turns positive.”

You can read all of Richard Sherman’s In This Corner columns for The MMQB here.